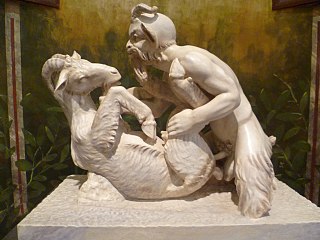

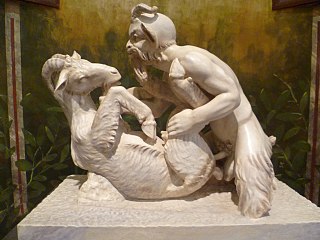

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes.

The Alexander Mosaic, also known as the Battle of Issus Mosaic, is a Roman floor mosaic originally from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy.

The Villa of the Papyri was an ancient Roman villa in Herculaneum, in what is now Ercolano, southern Italy. It is named after its unique library of papyri scrolls, discovered in 1750. The Villa was considered to be one of the most luxurious houses in all of Herculaneum and in the Roman world. Its luxury is shown by its exquisite architecture and by the large number of outstanding works of art discovered, including frescoes, bronzes and marble sculpture which constitute the largest collection of Greek and Roman sculptures ever discovered in a single context.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

In ancient Rome, the domus was the type of town house occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It was found in almost all the major cities throughout the Roman territories. The modern English word domestic comes from Latin domesticus, which is derived from the word domus. Along with a domus in the city, many of the richest families of ancient Rome also owned a separate country house known as a villa. Many chose to live primarily, or even exclusively, in their villas; these homes were generally much grander in scale and on larger acres of land due to more space outside the walled and fortified city.

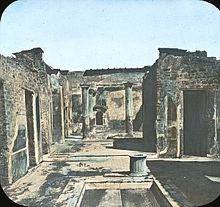

Cavaedium or atrium are Latin names for the principal room of an ancient Roman house, which usually had a central opening in the roof (compluvium) and a rainwater pool (impluvium) beneath it. The cavaedium passively collected, filtered, stored, and cooled rainwater. It also daylit, passively cooled and passively ventilated the house.

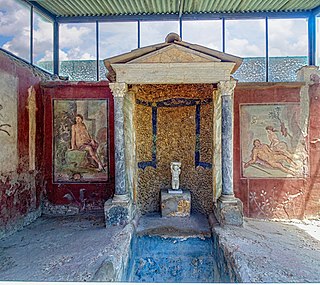

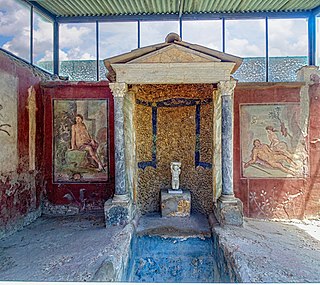

The House of the Vettii is a domus located in the Roman town Pompeii, which was preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house is named for its owners, two successful freedmen: Aulus Vettius Conviva, an Augustalis, and Aulus Vettius Restitutus. Its careful excavation has preserved almost all of the wall frescos, which were completed following the earthquake of 62 AD, in the manner art historians term the Pompeiian Fourth Style. The House of Vetti is located in region VI, near the Vesuvian Gate, bordered by the Vicolo di Mercurio and the Vicolo dei Vettii. The house is one of the largest domus in Pompeii, spanning the entire southern section of block 15. The plan is fashioned in a typical Roman domus with the exception of a tablinum, which is not included. There are twelve mythological scenes across four cubiculum and one triclinium. The house was reopened to tourists in January 2023 after two decades of restoration.

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa located in Torre Annunziata between Naples and Sorrento, in Southern Italy. It is also called the Villa Oplontis or Oplontis Villa A as it was situated in the ancient Roman town of Oplontis.

The House of the Faun, constructed in the 2nd century BC during the Samnite period, was a grand Hellenistic palace that was framed by peristyle in Pompeii, Italy. The historical significance in this impressive estate is found in the many great pieces of art that were well preserved from the ash of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is one of the most luxurious aristocratic houses from the Roman Republic, and reflects this period better than most archaeological evidence found even in Rome itself.

The House of Loreius Tiburtinus is renowned for well-preserved art, mainly in wall-paintings as well as its large gardens.

Stabiae was an ancient city situated near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia and approximately 4.5 km southwest of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, and being only 16 km (9.9 mi) from Mount Vesuvius, it was largely buried by tephra ash in 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in this case at a shallower depth of up to 5 m.

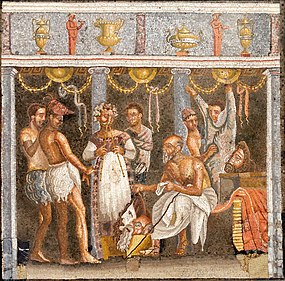

Achilles and Briseis is an ancient Roman painting from the 1st-century AD, depicting the scene from the Iliad where the captured Trojan princess and priestess Briseis is taken away from Achilles by the order of Agamemnon. It was found in the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii, Italy. The image is painted in distemper, similar to coloured white-washing and intermediary between fresco and paint. It was moved to the Naples National Archaeological Museum, where it remains.

The House of Sallust was an elite residence (domus) in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii and among the most sumptuous of the city.

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

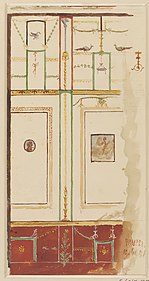

Wilhelm Johann Karl Zahn was a German architect, painter, art critic and design researcher particularly of Roman interior designs found in the ruins of Pompeii. Wilhelm was born as the fourth of five children of painter Bernhard Zahn, and his wife, Christiane, née Weis according to church records. He attended high schools in Bückeburg and Rinteln where he received a universal education. It was in Rinteln where Zahn studied the classics under a Professor Stein who Zahn remembered with particular affection.

Several non-native societies had an influence on Ancient Pompeian culture. Historians’ interpretation of artefacts, preserved by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79, identify that such foreign influences came largely from Greek and Hellenistic cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt. Greek influences were transmitted to Pompeii via the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, which were formed in the 8th century BC. Hellenistic influences originated from Roman commerce, and later conquest of Egypt from the 2nd century BC.

The House of the Prince of Naples is a Roman domus (townhouse) located in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii near Naples, Italy. The structure is so named because the Prince and Princess of Naples attended a ceremonial excavation of selected rooms there in 1898.

The House of the Greek Epigrams is a Roman residence in the ancient town of Pompeii that was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. It is named after wall paintings with inscriptions from Greek epigrams in a small room (y) next to the peristyle.

The House of the Small Fountain, aka House of the Second Fountain or House of the Landscapes, is located in the Roman city of Pompeii and, with the rest of Pompeii, was preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in or after October 79 CE. It is located on the Via di Mercurio, a street running north from the Arch of Caligula, at its crossroads with Via delle Terme, and Via della Fortuna, to Pompeii's fortification tower XI in the northwest part of the city. The street is named after a public fountain at VI.8.24 with a relief of the god, Mercury. Insula 8 is on the west side of the street. The house is named after a mosaic fountain adorned with shells at the rear of its peristyle. The property is immediately adjacent to the House of the Large Fountain, a structure with an even larger mosaic fountain adorned with shells and marble sculptures of theatrical masks excavated earlier in 1826. So the size difference between the fountains was used to distinguish the two structures.

The House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto is a Roman house in Pompeii with well-preserved wall paintings in both the late Third Style as well as the Fourth Style.