The Bible translations into the languages of Taiwan are into Taiwanese, Hakka, Amis, and other languages of Taiwan.

The Bible translations into the languages of Taiwan are into Taiwanese, Hakka, Amis, and other languages of Taiwan.

In Taiwan, education from kindergarten to college is done in Mandarin Chinese (Chinese :國語). Chinese is used in government offices and large corporations. The Bible text in Mandarin Chinese is in Traditional Chinese, written vertically, rather than in Simplified Chinese, written horizontally.

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2024) |

The majority of the Taiwan people speak Taiwanese, sometimes called Taiwanese Hokkien or Southern Min (Chinese : 閩南語 ; pinyin :Mǐnnányǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Bân-lâm-gí/gú) because their ancestors came from the southern part of China's Fujian Province (Chinese : 福建 ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Hok-kiàn), which has the abbreviated appellation Min (Chinese : 閩 ; pinyin :Mǐn; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Bân).

In 1916, Thomas Barclay finished the New Testament translation into Taiwanese Hokkien, followed by the Old Testament translation using Latin script in 1930. He carried out the translation with Chinese assistants in Xiamen, Fujian. His complete Bible, now called the Amoy Romanized Bible (Chinese :廈門音羅馬字聖經; pinyin :Xiàményīn Luómǎzì Shèngjīng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Ē-mn̂g-im Lô-má-jī Sèng-keng), was published in Shanghai in 1933. [1] The copies of this translation was once confiscated by the Taiwan Garrison Command during the martial law era for "obstructing of the Kuo-yu policy". In 1996, this Bible was transliterated into Chinese characters, and called the Taiwanese Han Character Bible (pinyin :Táiyǔ Hànzì Běn Shèngjīng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Tâi-gí Hàn-jī Pún Sèng-keng). [2] [3] A new revision of this Bible translation, the Taiwanese Bible: Today's Taiwanese Version (Chinese :台語漢字本聖經; pinyin :Táiyǔ Hànzì Běn Shèngjīng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī :Tâi-gí Hàn-jī Pún Sèng-keng) using Latin and Han script was completed in late 2021. [4]

The Ko–Tân (Kerygma) Colloquial Taiwanese Version of the New Testament (Sin-iok) in Pe̍h-ōe-jī, also known as the Red Cover Bible (Âng-phoê Sèng-keng), was published in 1973 as an ecumenical effort between the Protestant Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Roman Catholic mission Maryknoll. This translation used a more modern vocabulary (somewhat influenced by Mandarin), and reflected the central Taiwan dialect, as the Maryknoll mission was based near Tâi-tiong. It was soon confiscated by the Kuomintang government (which objected to the use of Latin orthography) in 1975.

A translation using the principle of functional equivalence, "Today's Taiwanese Romanized Version " (現代台語譯本; Hiān-tāi Tâi-gú E̍k-pún), containing only the New Testament, again in Pe̍h-ōe-jī, was published in 2008 [5] as a collaboration between the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Bible Society in Taiwan; a parallel-text version with both Han-character and Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthographies was published in 2013. [6] A translation of the Old Testament following the same principle was completed and the whole Bible was published in 2021 as a parallel-text volume. [7] [8]

Another translation using the principle of functional equivalence, "Common Taiwanese Bible" (Choân-bîn Tâi-gí Sèng-keng), with versions of Pe̍h-ōe-jī, Han characters and Ruby version (both Han characters and Pe̍h-ōe-jī) was published in 2015, available in printed and online.[ citation needed ]

| Translation [9] | John 3:16 |

|---|---|

| 1933 Taiwanese Bible Romanized Character Edition (Thomas Barclay) [10] | In-ūi Siōng-tè chiong to̍k-siⁿ ê Kiáⁿ siúⁿ-sù sè-kan, hō͘ kìⁿ-nā sìn I ê lâng bōe tîm-lûn, ōe tit-tio̍h éng-oa̍h; I thiàⁿ sè-kan kàu án-ni. |

| 1973 Ko–Tân/Kerygma “Red Cover Bible” (Âng-phoê Sèng-keng) | Siōng-chú chiah-ni̍h thiàⁿ sè-kan-lâng, só͘-í chiah chiong I ê Ko͘-kiáⁿ siúⁿ-sù in, thang hō͘ só͘ ū sìn I ê lâng m̄-bián bia̍t-bông, lâi tit-tio̍h éng-seng. |

| 1996 Taiwanese Bible Han Character Edition [11] | 因為上帝將獨生的子賞賜世間,互見若信伊的人,𣍐沈淪,會得著永活,伊疼世間到按呢。 |

| 2013 ≈ 2021 Today’s Taiwanese Romanized Version (Hiān-tāi Tâi-gú E̍k-pún) | Siōng-tè liân I to̍k-it ê Kiáⁿ to sù hō͘ sè-kan, beh hō͘ ta̍k ê sìn I ê lâng bián bia̍t-bông, hoán-tńg tit-tio̍h éng-oán ê oa̍h-miā, I chiah-ni̍h thiàⁿ sè-kan! |

| 2015 Common Taiwanese Bible" (Choân-bîn Tâi-gí Sèng-keng) | Siōng-tè chiah-ni̍h thiàⁿ sè-kan, sīm-chì siúⁿ-sù to̍k-seⁿ Kiáⁿ, hō͘ só͘-ū sìn I ê lâng bē tîm-lûn, hoán-tńg ē tit tio̍h éng-oán ê oa̍h-miā. |

The Hakka people live mainly in Taiwan's northwest areas, such as Taoyuan City, Hsinchu County and Miaoli County. The Hakka language is one of the four languages (the other three being Mandarin Chinese, Taiwanese and English) heard in the public transportation announcement in Taipei. Bible translation into Hakka language started in 1984. In 1993, the New Testament with the Psalms in Hakka was published, followed by the publication in 2012 of Hakka Bible: Today's Taiwan Hakka Version . [12]

The Amis people, living in Taiwan's east coast (Hualien, Taitung County and Pintung Counties), are the largest group among the Taiwanese indigenous peoples. In 1957, the Book of John was translated into Amis language using Bopomofo. After 1963, translation proceeded using Pinyin, and the New and Old Testaments in Amis were published in 1997. [13] A revised version of New Testament with Psalms and Proverbs was published in 2019.

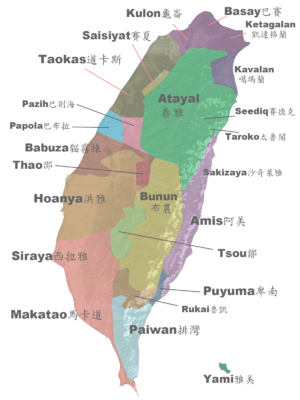

The Bible translations into other languages of Taiwan are done or being done: Paiwan language (New Testament/part of OT in 1993), Bunun language (NT in 1983; part of Old Testament in 2000), Atayal language (NT using Bopomofo in 1974; Romanized NT/part of OT in 2003; Complete Romanized text in 2022), Truku language (NT in 1960; NT/OT in 2005), Tao/Yami Language (NT in 1994; OT in progress), Rukai (NT in 2001; NT/OT in 2017), Tsou language (NT in 2013; OT in progress), Seediq language (NT/OT in 2020).

Taiwanese Hokkien, or simply Taiwanese, also known as Taiuanoe, Taigi, Taigu, Taiwanese Minnan, Hoklo and Holo, is a variety of the Hokkien language spoken natively by more than 70 percent of the population of Taiwan. It is spoken by a significant portion of those Taiwanese people who are descended from Hoklo immigrants of southern Fujian. It is one of the national languages of Taiwan.

Min is a broad group of Sinitic languages with about 70 million native speakers. These languages are spoken in Fujian province as well as by the descendants of Min-speaking colonists on the Leizhou Peninsula and Hainan and by the assimilated natives of Chaoshan, parts of Zhongshan, three counties in southern Wenzhou, the Zhoushan archipelago, Taiwan and scattered in pockets or sporadically across Hong Kong, Macau, and several countries in Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, Brunei. The name is derived from the Min River in Fujian, which is also the abbreviated name of Fujian Province. Min varieties are not mutually intelligible with one another nor with any other variety of Chinese.

Southern Min, Minnan or Banlam, is a group of linguistically similar and historically related Chinese languages that form a branch of Min Chinese spoken in Fujian, most of Taiwan, Eastern Guangdong, Hainan, and Southern Zhejiang. Southern Min dialects are also spoken by descendants of emigrants from these areas in diaspora, most notably in Southeast Asia, such as Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, Southern Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Southern and Central Vietnam, San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City. Minnan is the most widely-spoken branch of Min, with approximately 48 million speakers as of 2017–2018.

The Taitung Line, also known as the Hua-Tung line, is the southern section of the Eastern Line of the Taiwan Railways Administration. The line starts at the Hualien station and ends at the Taitung station. It is 161.5 km long, including the main segment of 155.7 km between Hualien and Taitung.

Chang Fei (Chinese: 張菲; pinyin: Zhāng Fēi; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tiuⁿ Húi ; born Chang Yan-ming is a Taiwanese singer and television personality.

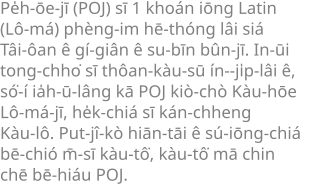

Pe̍h-ōe-jī, sometimes known as Church Romanization, is an orthography used to write variants of Hokkien Southern Min, particularly Taiwanese and Amoy Hokkien, and it is widely employed as one of the writing systems for Southern Min. During its peak, it had hundreds of thousands of readers.

Pha̍k-fa-sṳ (白話字) is an orthography similar to Pe̍h-ōe-jī and used to write Hakka, a variety of Chinese. Hakka is a whole branch of Chinese, and Hakka dialects are not necessarily mutually intelligible with each other, considering the large geographical region. This article discusses a specific variety of Hakka. The orthography was invented by the Presbyterian church in the 19th century. The Hakka New Testament published in 1924 is written in this system.

The languages of Taiwan consist of several varieties of languages under the families of Austronesian languages and Sino-Tibetan languages. The Formosan languages, a geographically designated branch of Austronesian languages, have been spoken by the Taiwanese indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Owing to the wide internal variety of the Formosan languages, research on historical linguistics recognizes Taiwan as the Urheimat (homeland) of the whole Austronesian languages family. In the last 400 years, several waves of Han emigrations brought several different Sinitic languages into Taiwan. These languages include Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and Mandarin, which have become the major languages spoken in present-day Taiwan.

"Taiwan the Formosa", also "Taiwan the Green", is a poem written by Taiwanese poet and clergyman Tīⁿ Jî-gio̍k, set to music between 1988 and 1993 by neo-Romantic Taiwanese composer Tyzen Hsiao. An English metrical translation was provided by Boris and Clare Anderson. The text represents an early example of the popular verse that emerged from the Taiwanese literature movement in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1994 Hsiao used this hymn to conclude his 1947 Overture for soprano, choir and orchestra.

The daguangxian is a Chinese bowed two-stringed musical instrument in the huqin family of instruments, held on the lap and played upright. It is used primarily in Taiwan and Fujian, among the Hakka and Min Nan people.

Waishengren, sometimes called mainlanders, are a group of migrants who arrived in Taiwan from mainland China between the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II in 1945, and Kuomintang retreat and the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. They came from various regions of mainland China and spanned multiple social classes.

There are many romanization systems used in Taiwan. The first Chinese language romanization system in Taiwan, Pe̍h-ōe-jī, was developed for Taiwanese by Presbyterian missionaries and has been promoted by the indigenous Presbyterian Churches since the 19th century. Pe̍h-ōe-jī is also the first written system of Taiwanese Hokkien; a similar system for Hakka was also developed at that time. During the period of Japanese rule, the promotion of roman writing systems was suppressed under the Dōka and Kōminka policy. After World War II, Taiwan was handed over from Japan to the Republic of China in 1945. The romanization of Mandarin Chinese was also introduced to Taiwan as official or semi-official standard.

Ji'an Township, is a rural township in Hualien County, Taiwan. It has 18 villages and a population of 83,750 inhabitants.

Taiwanese Language Phonetic Alphabet, more commonly known by its initials TLPA, is a romanization system for the Taiwanese Hokkien, Taiwanese Hakka, and indigenous Taiwanese languages. Based on Pe̍h-ōe-jī and first published in full in 1998, it was intended as a transcription system rather than as a full-fledged orthography.

The official romanization system for Taiwanese Hokkien in Taiwan is locally referred to as Tâi-uân Bân-lâm-gí Lô-má-jī Phing-im Hong-àn or Taiwan Minnanyu Luomazi Pinyin Fang'an, often shortened to Tâi-lô. It is derived from Pe̍h-ōe-jī and since 2006 has been one of the phonetic notation systems officially promoted by Taiwan's Ministry of Education. The system is used in the MoE's Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan. It is nearly identical to Pe̍h-ōe-jī, apart from: using ts tsh instead of ch chh, using u instead of o in vowel combinations such as oa and oe, using i instead of e in eng and ek, using oo instead of o͘, and using nn instead of ⁿ.

The Hakka Bible: Today's Taiwan Hakka Version (TTHV), is the most recent revised Hakka language translation of the Bible used by Hakka Protestants in Taiwan and overseas Hakka communities. Work on the translation commenced in 1984 with the TTHV New Testament & Psalms completed in 1993, Proverbs was published separately in 1995. The entire Bible was made available on April 11, 2012 at the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan's annual General Assembly meeting. An ecumenical dedication and thanksgiving ceremony was held on April 22, 2012 at the National Chiao Tung University in Hsinchu with over 1,200 Hakka Christians in attendance.

Taiwanese Phonetic Symbols constitute a system of phonetic notation for the transcription of Taiwanese languages, especially Taiwanese Hokkien. The system was designed by Professor Chu Chao-hsiang, a member of the National Languages Committee in Taiwan, in 1946. The system is derived from Mandarin Phonetic Symbols by creating additional symbols for the sounds that do not appear in Mandarin phonology. It is one of the phonetic notation systems officially promoted by Taiwan's Ministry of Education.

Taiwanese Hangul is an orthography system for Taiwanese Hokkien (Taiwanese). Developed and promoted by Taiwanese linguist Hsu Tsao-te in 1987, it uses modified Hangul letters to represent spoken Taiwanese, and was later supported by Ang Ui-jin. Because both Chinese characters and Hangul are both written in the space of square boxes, unlike letters of the Latin alphabet, the use of Chinese-Hangul mixed writing is able to keep the spacing between the two scripts more consistent compared to Chinese-Latin mixed writing.