Related Research Articles

The French Union was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the "French Empire". It was de jure the end of the "indigenous" status of French subjects in colonial areas.

French Sudan was a French colonial territory in the Federation of French West Africa from around 1880 until 1959, when it joined the Mali Federation, and then in 1960, when it became the independent state of Mali. The colony was formally called French Sudan from 1890 until 1899 and then again from 1921 until 1958, and had a variety of different names over the course of its existence. The colony was initially established largely as a military project led by French troops, but in the mid-1890s it came under civilian administration.

French West Africa was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan, French Guinea, Ivory Coast, Upper Volta, Dahomey and Niger. The federation existed from 1895 until 1958. Its capital was Saint-Louis, Senegal until 1902, and then Dakar until the federation's collapse in 1960.

Ahmed Sékou Touré was a Guinean political leader and African statesman who became the first president of Guinea, serving from 1958 until his death in 1984. Touré was among the primary Guinean nationalists involved in gaining independence of the country from France. He would later die in the United States in 1984.

Modibo Keïta was a Malian politician who served as the first President of Mali from 1960 to 1968. He espoused a form of African socialism. He was deposed in a coup d'état in 1968 by Moussa Traoré.

The Mali Federation was a federation in West Africa linking the French colonies of Senegal and the Sudanese Republic for two months in 1960. It was founded on 4 April 1959 as a territory with self-rule within the French Community and became independent after negotiations with France on 20 June 1960. Two months later, on 19 August 1960, the Sudanese Republic leaders in the Mali Federation mobilized the army, and Senegal leaders in the federation retaliated by mobilizing the gendarmerie ; this resulted in a tense stand-off, and led to the withdrawal from the federation by Senegal the next day. The Sudanese Republic officials resisted this dissolution, cut off diplomatic relations with Senegal, and defiantly changed the name of their country to Mali. For the brief existence of the Mali Federation, the premier was Modibo Keïta, who would later become the first President of Mali, and its government was based in Dakar, the eventual capital of Senegal.

Cheikh Anta Diop University, also known as the Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar, is a university in Dakar, Senegal. It is named after the Senegalese physicist, historian and anthropologist Cheikh Anta Diop and has an enrollment of over 60,000.

The French Community was the constitutional organization set up in 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which had reorganized the colonial empire in 1946. While the Community remained formally in existence until 1995, when the French Parliament officially abolished it, it had effectively ceased to exist and function by the end of 1960, by which time all the African members had declared their independence and left it.

Students Movement of the African and Malagasy Common Organization, generally called M.E.O.C.A.M., was an organization of African students in France. M.E.O.C.A.M. was founded of the initiative of Félix Houphouët-Boigny in November 1966, in order to counter the influence of the Federation of Students of Black Africa in France (F.E.A.N.F.). F.E.A.N.F. was seen by the Houphouët-Boigny regime as pro-communist and subversive.

Djibril Tamsir Niane was a Guinean historian, playwright, and short story writer.

École William Ponty was a government teachers' college in French West Africa, in what is now Senegal. The school is now in Kolda, Senegal, where it is currently known as École de formation d’instituteurs William Ponty. It is associated with the French university IUFM at Livry-Gargan (France).

IFAN is a cultural and scientific institute in the nations of the former French West Africa. Founded in Dakar, Senegal in 1938 as the Institut français d’Afrique noire, the name was changed only in 1966. It was headquartered in what is now the building of the IFAN Museum of African Arts. Since its founding, its charge was to study the language, history, and culture of the peoples ruled by French colonialism in Africa.

The African Regroupment Party was a political party in the French African colonies.

The Youth Council of the French Union was a coordinating body of youth organizations in the French Union. CJUF was founded in 1950. The organization had its headquarters in Paris and held annual congresses.

The General Union of Negro African Workers, more widely known by its French name Union générale des travailleurs d'Afrique noire, was a pan-African trade union organization. Ahmed Sékou Touré was the main leader of the organization. In its heyday, around 90% of the trade unions in Francophone West Africa were affiliated to UGTAN.

Kojo Tovalou Houénou was a prominent African critic of the French colonial empire in Africa. Born in Porto-Novo to a wealthy father and a mother who belonged to the royal family of the Kingdom of Dahomey, he was sent to France for education at the age of 13. There he received a law degree, medical training, and served in the French armed forces as an army doctor during World War I. Following the war, Houénou became a minor celebrity in Paris; dating actresses, writing books as a public intellectual, and making connections with many of the elite of French society.

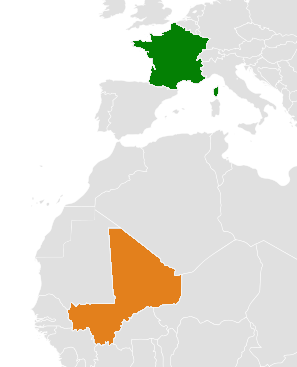

France–Mali relations are the current and historical relations between France and Mali.

The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics is a report written by Senegalese academic and writer Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy, first published online in November 2018 in a French original version and an authorised English translation.

Benin–Turkey relations are the foreign relations between Benin and Turkey. Turkey has an embassy in Cotonou since 2014, while the Beninois embassy in Ankara opened in 2013, however the embassy was closed in 2020.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Schmidt, Elizabeth. Cold War and Decolonization in Guinea, 1946-1958 . Western African studies. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007. p. 127

- ↑ Martens, Ludo, and Hilde Meesters. Sankara, Compaoré et la révolution burkinabè . Anvers: Editions EPO, 1989. p. 117

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rice, Louisa (2013). "Between Empire and Nation: Francophone West African Students and Decolonization". Atlantic Studies. doi:10.1080/14788810.2013.764106.

- ↑ Diané, Charles. Les grandes heures de la FEANF . Paris: Ed. Chaka, 1990. pp. 41-42

- 1 2 3 Diané, Charles. Les grandes heures de la FEANF . Paris: Ed. Chaka, 1990. pp. 42-43

- ↑ Bianchini, Pascal. Ecole et politique en Afrique noire: sociologie des crises et des réformes du système d'enseignement au Sénégal et au Burkina Faso (1960-2000) . Paris: Karthala, 2004. p. 64

- ↑ Diané, Charles. Les grandes heures de la FEANF . Paris: Ed. Chaka, 1990. p. 44

- ↑ Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice. Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. p. 214

- ↑ O'Toole, Thomas, and Janice E. Baker. Historical Dictionary of Guinea . Historical dictionaries of Africa, no. 94. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, 2005. p. 85

- 1 2 Schmidt, Elizabeth. Cold War and Decolonization in Guinea, 1946-1958 . Western African studies. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007. p. 143

- ↑ Diané, Charles. Les grandes heures de la FEANF . Paris: Ed. Chaka, 1990. pp. 55-63

- ↑ Bianchini, Pascal. Ecole et politique en Afrique noire: sociologie des crises et des réformes du système d'enseignement au Sénégal et au Burkina Faso (1960-2000) . Paris: Karthala, 2004. p. 123

- 1 2 Diané, Charles. Les grandes heures de la FEANF . Paris: Ed. Chaka, 1990. p. 20