Potash includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form. The name derives from pot ash, plant ashes or wood ash soaked in water in a pot, the primary means of manufacturing potash before the Industrial Era. The word potassium is derived from potash.

Polyhalite is an evaporite mineral, a hydrated sulfate of potassium, calcium and magnesium with formula: K2Ca2Mg(SO4)4·2H2O. Polyhalite crystallizes in the triclinic system, although crystals are very rare. The normal habit is massive to fibrous. It is typically colorless, white to gray, although it may be brick red due to iron oxide inclusions. It has a Mohs hardness of 3.5 and a specific gravity of 2.8. It is used as a fertilizer.

ICL Group Ltd. is a multi-national manufacturing concern that develops, produces and markets fertilizers, metals and other special-purpose chemical products. ICL serves primarily three markets: agriculture, food and engineered materials. ICL produces approximately a third of the world's bromine, and is the world's sixth-largest potash producer. It is a manufacturer of specialty fertilizers and specialty phosphates, flame retardants and water treatment solutions.

Boulby is a hamlet in the Loftus parish, located within the North York Moors National Park. It is in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England. The hamlet is located off the A174, near Easington and 1-mile (1.6 km) west of Staithes.

The UK Dark Matter Collaboration (UKDMC) (1987–2007) was an experiment to search for weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs). The consortium consisted of astrophysicists and particle physicists from the United Kingdom, who conducted experiments with the ultimate goal of detecting rare scattering events which would occur if galactic dark matter consists largely of a new heavy neutral particle. Detectors were set up 1,100 m (3,600 ft) underground in a halite seam at the Boulby Mine in North Yorkshire.

SNOLAB is a Canadian underground science laboratory specializing in neutrino and dark matter physics. Located 2 km below the surface in Vale's Creighton nickel mine near Sudbury, Ontario, SNOLAB is an expansion of the existing facilities constructed for the original Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO) solar neutrino experiment.

Lockwood is a civil parish in the unitary authority of Redcar and Cleveland with ceremonial association with North Yorkshire, England.

The Whitby, Redcar and Middlesbrough Union Railway (WRMU), a.k.a. the Whitby–Loftus Line, was a railway line in North Yorkshire, England, built between 1871 and 1886, running from Loftus on the Yorkshire coast to the Esk at Whitby, and connecting Middlesbrough to Whitby along the coast.

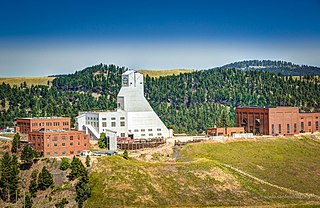

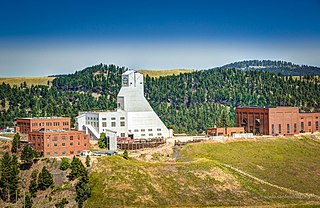

The Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), or Sanford Lab, is an underground laboratory in Lead, South Dakota. The deepest underground laboratory in the United States, it houses multiple experiments in areas such as dark matter and neutrino physics research, biology, geology and engineering. There are currently 28 active research projects housed within the facility.

The Large Underground Xenon experiment (LUX) aimed to directly detect weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) dark matter interactions with ordinary matter on Earth. Despite the wealth of (gravitational) evidence supporting the existence of non-baryonic dark matter in the Universe, dark matter particles in our galaxy have never been directly detected in an experiment. LUX utilized a 370 kg liquid xenon detection mass in a time-projection chamber (TPC) to identify individual particle interactions, searching for faint dark matter interactions with unprecedented sensitivity.

Mining in the United Kingdom produces a wide variety of fossil fuels, metals, and industrial minerals due to its complex geology. In 2013, there were over 2,000 active mines, quarries, and offshore drilling sites on the continental land mass of the United Kingdom producing £34bn of minerals and employing 36,000 people.

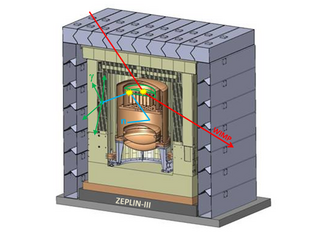

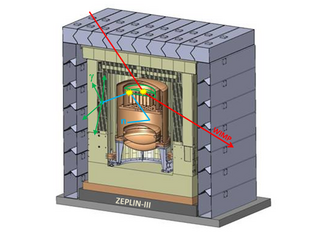

The ZEPLIN-III dark matter experiment attempted to detect galactic WIMPs using a 12 kg liquid xenon target. It operated from 2006 to 2011 at the Boulby Underground Laboratory in Loftus, North Yorkshire. This was the last in a series of xenon-based experiments in the ZEPLIN programme pursued originally by the UK Dark Matter Collaboration (UKDMC). The ZEPLIN-III project was led by Imperial College London and also included the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and the University of Edinburgh in the UK, as well as LIP-Coimbra in Portugal and ITEP-Moscow in Russia. It ruled out cross-sections for elastic scattering of WIMPs off nucleons above 3.9 × 10−8 pb from the two science runs conducted at Boulby.

Richard Jeremy Gaitskell is a physicist and professor at Brown University and a leading scientist in the search for particle dark matter. He is co-founder, a principal investigator, and co-spokesperson of the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment, which announced world-leading first results on October 30, 2013. He is also a leading investigator in the new LUX-Zeplin (LZ) dark matter experiment.

The Yorkshire Coast runs from the Tees estuary to the Humber estuary, on the east coast of England. The cliffs at Boulby are the highest on the east coast of England, rising to 660 feet (200 m) above the sea level.

Sirius Minerals plc was a fertilizer development company based in the United Kingdom. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange until it was acquired by Anglo American in March 2020.

Woodsmith Mine is a deep planned potash and polyhalite mine located near the hamlet of Sneatonthorpe, Whitby in North Yorkshire, England. The venture was started by York Potash Ltd, which became a subsidiary of Sirius Minerals plc whose primary focus was the development of the polyhalite project. The project will mine the world's largest known deposit of polyhalite – a naturally occurring mineral. Because the project would require mining to be undertaken in the North York Moors National Park, many objections were raised to the mine and the proposed underground conveyor that would be installed to transport the raw material offsite to a plant on Teesside 23 miles (37 km) away.

The Woodsmith Mine Tunnel is a 23-mile (37 km) long tunnel that will stretch between Woodsmith Mine at Sneatonthorpe near Whitby in North Yorkshire and the Wilton International complex on Teesside, England. The tunnel has been in development since 2016, but cutting of the tunnel bore did not start until April 2019, with an original projected completion date of 2021, now projected to 2030. By June 2024 tunnelling had advanced 18 miles (29 km), 78% complete.

Grinkle Mine, was an ironstone mine working the main Cleveland Seam near to Roxby in North Yorkshire, England. Initially, the ironstone was mined specifically for the furnaces at the Palmer Shipbuilders in Jarrow on the River Tyne, but later, the mine became independent of Palmers. To enable the output from the mine to be exported, a 3-mile (4.8 km) narrow-gauge tramway was constructed that ran across three viaducts and through two tunnels to the harbour of Port Mulgrave, where ships would take the ore directly to Tyneside.

Kilton Viaduct was a railway viaduct that straddled Kilton Beck, near to Loftus, in North Yorkshire, England. The viaduct was opened to traffic in 1867, however in 1911, with the viaduct suffering subsidence from the nearby ironstone mining, the whole structure was encased in waste material from the mines creating an embankment which re-opened fully to traffic in 1913. The railway closed in 1963, but then in 1974, it re-opened as part of the freight line to Boulby Mine carrying potash traffic.

The Boulby line is a freight-only railway line in Redcar and Cleveland, England. The line was opened in stages between 1865 and 1882, being part of two railways that met at Brotton railway station. Passenger trains along the line ceased in 1960, and since then it has been a freight-only line dedicated to the potash and polyhalite traffic from Boulby, and steel products into Skinningrove Steelworks.