Iconoclastic period

While a certain number of works of art and in particular manuscripts were destroyed, some manuscripts were nevertheless produced during this period from the seventh to the mid-ninth century, particularly in the peripheral areas of the empire, such as in Palestine, or in Italy. It is probably in the latter that a copy of the Sacra Parallela (BNF, Greek 923) was produced, which contains more than 1600 illustrations located in the margins of the manuscript. The style is very distant from the models of the late antiquity, it is notable in its use thick black brush strokes and its use of the gold ground technique. But it was in Constantinople, in a monastic scriptorium, that the Chludov Psalter was painted in the middle of the ninth century, it contains numerous figurative decorations in the margins, including a representation of a scene of the destruction of an icon. [5]

Renaissance

Illumination flourished starting from the late 9th century to the 12th century. Several hundred manuscripts are preserved from this period , they are most often parchment codices, which take precedence over scrolls, although the latter did not completely disappear as shown in the Joshua Roll (Vatican Apostolic Library, Palat.Grec 431). However, they are very often poorly preserved. As the techniques implemented for the coloring recommended either the production of a very thin layer of paint which does not allow them to set correctly on the parchment, or on the contrary the application of a very thick layer which has tendency to flake off. Moreover, it is often difficult to be able to date them and locate their production due to the frequent absence of a colophon. [6]

Illumination from this period most often consists of miniatures either full-page or on part of the page such as margin decorations and less frequently initials of simple ornamental of vegetal or zoomorphic decoration. [7]

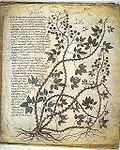

The psalters are the most frequent illuminated texts. They are of two types: the monastic psalters, of modest dimensions, whose decorations are found in the margins of almost all pages. This is the case of the Chludov psalter and the Theodore Psalter dated 1066 (BL, Add.19352). The aristocratic psalters are, on the contrary, large in size, and decorated with sumptuous full-page miniatures but in a reduced number, most often depicting biblical royal figures. The Paris Psalter is the most famous example, perhaps made for Constantine VII. Among the other manuscripts, there are octateuchs as well as evangeliaries, which are decorated with portraits of evangelists, scenes from the life of Christ and Eusebian Canons. Many texts of the Church Fathers are also copied and illustrated such as those of John Chrysostom and Gregory of Nazianzus (like the Parisian manuscript Grec 510), as well as menologia. Secular works inherited from antiquity are also copied and decorated, including medical works with Dioscorides again, hunting treatises like that of Oppian of Syria or war treatises. Some chronicles are also illuminated like the chronicle of Skylitzes, now kept in Madrid (National Library of Spain, Graecus Vitr. 26-2). [8]

Among the sources of inspiration, illumination of the late antiquity is still present. However, many manuscripts, including religious ones, also draw their iconography from scenes of daily life. Furthermore, Islamic art provided models for ornamental motifs and zoomorphic decorations. [9]

An evolution stands out during the period. While the first manuscripts of the 10th century, under ancient influence, favored naturalistic or even illusionist representations, from the end of this century, the works presented more hieratic figures, with more elongated dimensions, with a rise of the use of gilded backgrounds. The menologion of Basil II (BAV) as well as his psalter (Biblioteca Marciana, Gr.Z17) represent the beginnings of this style, while the Homilies of Chrysostom (BNF Coislin 79) represents its height in the middle of the eleventh century. The ornamental motifs increased in variations, as can be seen in the Gospel of Paris (BNF Gr.54). During the twelfth century, illuminators associated ornaments and figurative scenes with abundant miniature frames, initials and decorations on the margins. This is the case of the Seraglio Octateuch (Topkapi Palace) and another manuscript of the Gregory of Nazianzuz in Paris (BNF, Gr.550). The apogee of this style is found in the Homilies of James of Kokkinobaphos (BNF, Gr.1208), which also considerably renewed the iconography in use at the time. [10]

Latin interlude

During the period of the occupation of Constantinople by the Crusaders, between 1204 and 1261, following its sacking, Byzantine art experienced an interval during which it was no longer a priority, the new rulers showing little interest to the art. Only a small group of Byzantine manuscripts are dated to this period, with most of them mixing Latin and Byzantine elements. One of them, a bilingual Latin-Greek gospel book, is still kept at the National Library of France; the Greek-Latin tetra-gospel (Gr.54), which was probably intended for a high Latin dignitary, religious or layman. It was never completed. [11]

Palaeologian era

The field of illumination remained more in permanence during the time of the Palaiologos than in innovation. The manuscripts of this period take up the models developed in previous periods, drawing inspiration from or even directly imitating the manuscripts of Macedonian or Komnenian art. The works were getting increasingly made on paper and no longer on parchment, the production declined with what remained of the empire. Some works show an influence of Western illumination of the time, such as a Book of Job written by a scribe from Mistra named Manuel Tzykandyles around 1362 (BNF, Gr.132). [12]

Nevertheless, some manuscripts took advantage of the revival of monumental painting during the fourteenth century, with much more expressive and virtuoso representations, particularly in portraits. These are found in a manuscript of theological works of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (BNF, Gr.1242) in which are painted in addition to a Transfiguration, the portraits of the owner as an emperor and as a monk. This is also the case with a manuscript from of Hippocrates depicting the Grand Duke Alexios Apokaukos (BNF, Gr.2144) and another from the Bodleian library (Typicon, Cod.Gr.35) depicting nuns around their abbess of Monastery of the Good Hope in Constantinople. [13]