Tredegar is a town and community situated on the banks of the Sirhowy River in the county borough of Blaenau Gwent, in the southeast of Wales. Within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire, it became an early centre of the Industrial Revolution in Wales. The relevant wards collectively listed the town's population as 15,103 in the UK 2011 census.

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

CSS Fredericksburg was a casemate ironclad that served as part of the James River Squadron of the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Laid down in 1862 and Launched the following year, she did not see action until 1864 due to delays in receiving her armor and guns. After passing through the obstructions at Drewry's Bluff in May 1864, she participated in several minor actions on the James River and fought in the Battle of Chaffin's Farm from September 29 to October 1. On January 23 and 24, 1865, she was part of the Confederate fleet at the Battle of Trent's Reach, and was one of only two Confederate ships to make it past the obstructions at Trent's Reach. After the Confederate attack failed, Fredericksburg withdrew with the rest of the James River Squadron. On April 3, as the Confederates were abandoning Richmond, Fredericksburg and the other vessels of the James River Squadron were burned. Her wreck was located in the 1980s, buried under sediment.

Joseph Reid Anderson was an American civil engineer, industrialist, politician and soldier. During the American Civil War he served as a Confederate general, and his Tredegar Iron Company was a major source of munitions and ordnance for the Confederate States Army. Starting with a small forge and rolling mill in the mid-1830s, It was a flourishing operation by 1843 when he leased it. He eventually bought the company outright in 1848 and forcefully and aggressively built Tredegar Iron Works into the South's largest and most significant iron works. When the Civil War broke out he entered the Army as a brigadier general in 1861. Shortly after he was wounded and then resigned from the Army returning to the iron works. It was the Confederacy's major source of cannons and munitions, employing some 900 workers, most of whom were slaves. His plant was confiscated by the Union army at the end of the war, but returned to him in 1867 and he remained president until his death. Anderson was very active in local civic and political affairs.

The American Civil War Museum is a multi-site museum in the Greater Richmond Region of central Virginia, dedicated to the history of the American Civil War. The museum operates three sites: The White House of the Confederacy, American Civil War Museum at Historic Tredegar in Richmond, and American Civil War Museum at Appomattox. It maintains a comprehensive collection of artifacts, manuscripts, Confederate imprints, and photographs.

Sloss Furnaces is a National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, Alabama in the United States. It operated as a pig iron-producing blast furnace from 1882 to 1971. After closing, it became one of the first industrial sites in the U.S. to be preserved and restored for public use. In 1981, the furnaces were designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior.

In American Colonial history, the Iron Act, also called the Importation, etc. Act 1750, was one of the legislative measures introduced by the British Parliament, within its system of Trade and Navigation Acts. The Act sought to increase the importation of pig and bar iron from its American colonies and to prevent the building of iron-related production facilities within these colonies, particularly in North America where these raw materials were identified. The dual purpose of the act was to increase manufacturing capacity within Great Britain itself, and to limit potential competition from the colonies possessing the raw materials.

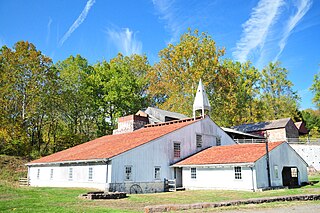

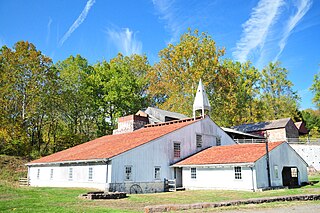

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site in southeastern Berks County, near Elverson, Pennsylvania, is an example of an American 19th century rural "iron plantation," whose operations were based around a charcoal-fired cold-blast iron blast furnace. The significant restored structures include the furnace group (blast furnace, water wheel, blast machinery, cast house and charcoal house), as well as the ironmaster's house, a company store, the blacksmith's shop, a barn and several worker's houses.

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

The Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama, also known as the Tannehill Museum, is an industrial museum that demonstrates iron production in the nineteenth-century Alabama located at Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park in McCalla, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama. Opened in 1981, it covers 13,000 square feet (1,200 m2).

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within Tennessee, it relocated most of its business to Alabama in the late nineteenth century, following protests over its use of free convict labor. With a sizable real estate portfolio, the company owned several Birmingham satellite towns, including Ensley, Fairfield, Docena, Edgewater and Bayview. It also established a coal mining camp it sold to U.S. Steel which developed it into the Westfield, Alabama planned community.

French weapons in the American Civil War had a key role in the conflict and encompassed most of the sectors of weaponry of the American Civil War (1861–1865), from artillery to firearms, submarines and ironclad warships. The effect of French weapons was especially significant in field artillery and infantry. These weapons were either American productions based on French designs, or sometimes directly imported from France.

The Williams gun was a Confederate gun that was classified as a 1-lb cannon. It was designed by Captain D.R. Williams, of Covington, Kentucky, who later served as an artillery captain with a battery of his design. It was a breech-loading, rapid-fire cannon that was operated by a hand-crank. The barrel was four feet long and a 1.57-inch caliber. The hand crank opened the sliding breech which allowed the crew to load a round and cap the primer. As the crank was continued, it closed the breech and automatically released the hammer. The effective range was 800 yards but the maximum range was 2000 yards.

Thomas Williamson Means was a settler of Hanging Rock, Ohio, and a native of South Carolina. Together with his brother Hugh he became notable in Ashland, Kentucky, after he built the Buena Vista Furnace and became a director of the Kentucky Coal, Iron & Manufacturing Company. He was also the father of Ashland Mayor John Means. Means owned furnaces in Alabama, Kentucky, Ohio, and Virginia.

Ebbw Vale Steelworks was an integrated steel mill located in Ebbw Vale, South Wales. Developed from 1790, by the late 1930s it had become the largest steel mill in Europe. Nationalized after World War II, as the steel industry changed to bulk handling, iron and steel making was ceased in the 1970s, as the site was redeveloped as a specialised tinplate works. Closed by Corus in 2002, the site is being redeveloped in a joint-partnership between Blaenau Gwent Council and the Welsh Government.

Tredegar Iron and Coal Company was an important 19th century ironworks in Tredegar, Wales, which due to its need for coke became a major developer of coal mines and particularly the Sirhowy Valley of South Wales. It is most closely associated with the Industrial Revolution and coal mining in the South Wales Valleys.

The Low Moor Ironworks was a wrought iron foundry established in 1791 in the village of Low Moor about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. The works were built to exploit the high-quality iron ore and low-sulphur coal found in the area. Low Moor made wrought iron products from 1801 until 1957 for export around the world. At one time it was the largest ironworks in Yorkshire, a major complex of mines, piles of coal and ore, kilns, blast furnaces, forges and slag heaps connected by railway lines. The surrounding countryside was littered with waste, and smoke from the furnaces and machinery blackened the sky. Today Low Moor is still industrial, but the pollution has been mostly eliminated.

The Shelby Iron Company was an iron manufacturing company that operated an ironworks in Shelby, Alabama. The iron company produced iron for the Confederate States of America and was destroyed towards the end of the American Civil War. The company continued to produce iron until the early part of the 20th century.

Elisha Peck (1789-1851) was a Massachusetts-born merchant who formed a partnership with Anson Green Phelps. He ran the British side of their business from Liverpool for about thirteen years. The partnership ended in 1834 after an accident at their New York warehouse claimed the lives of seven people. Their assets were divided and Peck took ownership of the metal manufacturing plants at Haverstraw, New York. Phelps continued with the mercantile business that he had developed with Peck, forming a new company called Phelps Dodge.

The Lithgow Blast Furnace is a heritage-listed former blast furnace and now park and visitor attraction at Inch Street, Lithgow, City of Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1906 to 1907 by William Sandford Limited. It is also known as Eskbank Ironworks Blast Furnace site; Industrial Archaeological Site. The property is owned by Lithgow City Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.