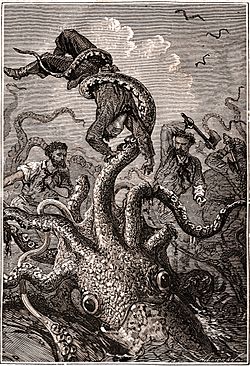

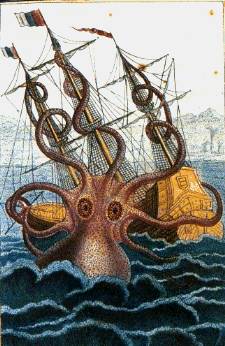

Cephalopod attacks on humans have been reported since ancient times. A significant portion of these attacks are questionable or unverifiable tabloid stories. Cephalopods are members of the class Cephalopoda, which includes all squid, octopuses, cuttlefish, and nautiluses. Some members of the group are capable of causing injury or death to humans.