Related Research Articles

The Public Works Administration (PWA), part of the New Deal of 1933, was a large-scale public works construction agency in the United States headed by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. It was created by the National Industrial Recovery Act in June 1933 in response to the Great Depression. It built large-scale public works such as dams, bridges, hospitals, and schools. Its goals were to spend $3.3 billion in the first year, and $6 billion in all, to supply employment, stabilize buying power, and help revive the economy. Most of the spending came in two waves, one in 1933–1935 and another in 1938. Originally called the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, it was renamed the Public Works Administration in 1935 and shut down in 1944.

Druid Hills is a community which includes both a census-designated place (CDP) in unincorporated DeKalb County, Georgia, United States, as well as a neighborhood of the city of Atlanta. The CDP's population was 14,568 at the 2010 census. The CDP formerly contained the main campus of Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); however, they were annexed by Atlanta in 2018. The Atlanta-city section of Druid Hills is one of Atlanta's most affluent neighborhoods with a mean household income in excess of $238,500.

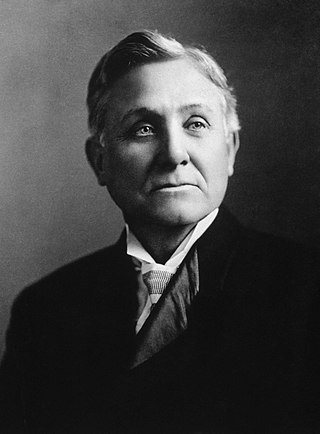

Asa Griggs Candler Sr. was an American business tycoon and politician who in 1888 purchased the Coca-Cola recipe for $238.98 from chemist John Stith Pemberton in Atlanta, Georgia. Candler founded The Coca-Cola Company in 1892 and developed it as a major company.

Ivan Earnest Allen Jr., was an American businessman who served two terms as the 52nd mayor of Atlanta, during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

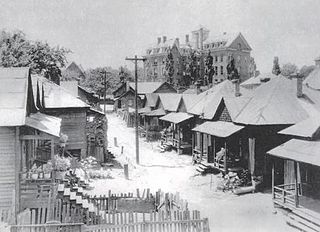

Techwood Homes was an early public housing project in the Atlanta, Georgia in the United States, opened just before the First Houses. The whites-only Techwood Homes replaced an integrated settlement of low-income people known as Tanyard Bottom or Tech Flats. It was completed on August 15, 1936, but was dedicated on November 29 of the previous year by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The new whites-only apartments included bathtubs and electric ranges in each unit, 189 of which had garages. Central laundry facilities, a kindergarten and a library were also provided. Techwood Homes was demolished in advance of the 1996 Olympics and is now Centennial Place Apartments.

Centennial Hill is district at the northern edge of Downtown Atlanta, Georgia. The name was originally coined by Hines Interests and applied only to their planned development in the area. Although the development was never started and the land later sold, the name remained and became associated with the whole neighborhood. Due in part to the Georgia Aquarium and to renewed interest in city living, Centennial Hill is undergoing a development boom estimated at over US$1 billion. This includes Allen Plaza, an eight-block complex that spans many side streets and borders Ivan Allen. The seasoned developer's project had already delivered the north end of downtown a modern fresh look, with glass buildings that accommodated Southern Co. and Ernst & Young looming over the Downtown Connector and a W Hotel nearby.

The Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA) is an agency that provides affordable housing for low-income families in Atlanta. Today, the AHA is the largest housing agency in Georgia and one of the largest in the United States, serving approximately 50,000 people.

The American Housing Act of 1949 was a landmark, sweeping expansion of the federal role in mortgage insurance and issuance and the construction of public housing. It was part of President Harry Truman's program of domestic legislation, the Fair Deal.

The Boulevard Gardens Apartments is a 960-unit apartment complex at 54th Street and 31st Avenue in Woodside, Queens, New York City. It opened in June 1935, during the Great Depression. They were designed by architect Theodore H. Englehardt for the Cord Meyer Development Corporation; the design was based on an apartment complex Elgelhardt designed in Forest Hills.

Joe Rand Beckett was an American veteran of World War I, prominent lawyer in Indianapolis, Indiana, and a member of the Indiana Senate representing Johnson County and Marion County in 1929, 1931 and the special session in 1932 as well as assistant attorney general for the state. Shortly thereafter, he led the drive to build modern housing for low income residents of Indianapolis to improve conditions in the city.

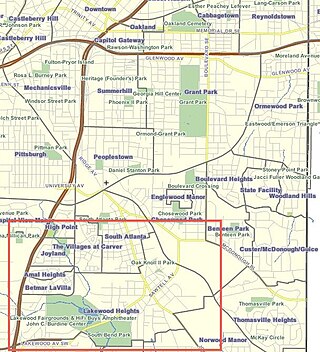

Lakewood Heights is a primarily Black neighborhood in southeast Atlanta. It is bounded by:

Tanyard Bottom, also known as Tech Flats, was a shantytown just south of Georgia Tech along Techwood Drive. It was replaced in the 1930s with the Techwood Homes, America's first public housing project. It is currently the site of Centennial Place Apartments.

Callanwolde Fine Arts Center is a 501(c)(3) non-profit community arts center that offers classes and workshops for all ages in visual, literary and performing arts. Special performances, gallery exhibits, outreach programs and fundraising galas are presented throughout the year. Callanwolde is also involved in community outreach, specializing in senior wellness, special needs, veterans, and low income families.

Beaver Slide or Beavers' Slide was an African American slum area near Atlanta University documented as early as 1882. It was replaced by the University Homes public housing project in 1937, which was razed in 2008–9.

In 1996, The Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA) created the financial and legal model for mixed-income communities or MICs, that is, communities with both owners and renters of differing income levels, that include public-assisted housing as a component. This model is used by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's HOPE VI revitalization program. As of 2011, it has resulted in all housing projects having been demolished, with partial replacement by MICs.

In 1994 the Atlanta Housing Authority, encouraged by the federal HOPE VI program, embarked on a policy created for the purpose of comprehensive revitalization of severely distressed public housing developments. These distressed public housing properties were replaced by mixed-income communities.

Langston Terrace Dwellings are historic structures located in the Langston portion of the Carver/Langston neighborhoods in the Northeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. The apartments were built between 1935 and 1938 and they were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

Oak Knoll is a section of the Lakewood Heights neighborhood of southeastern Atlanta which received national attention during its construction phase in 1937 for its innovative financing model.

The Olympic Legacy Program was an initiative taken in effort to revitalize many of Atlanta’s public housing projects in the early 1990s in preparation for hosting the 1996 Olympic Games. The initiative, guided by the principals of “new urbanism” was proposed as a way to transform thirteen former projects scattered throughout the city. The initiative began with Techwood Homes in downtown Atlanta, Clark Howell Homes, and continuing to several other projects in each zone. The program was led by former Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA) CEO Renee Glover. While the project's ultimate effect was to reduce the concentration of poverty in the city, and improve neighborhoods, employment and education opportunities, finding housing for some of the poor shifted to suburban housing which lacked many of the social services of government housing.

Slum clearance in the United States has been used as an urban renewal strategy to regenerate derelict or run-down districts, often to be replaced with alternative developments or new housing. Early calls were made during the 19th century, although mass slum clearance did not occur until after World War II with the introduction of the Housing Act of 1949 which offered federal subsidies towards redevelopments. The scheme ended in 1974 having driven over 2,000 projects with costs in excess of $50 billion.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Biographical note, "Palmer, Charles F.", Emory Library EmoryFindingAid

- ↑ Carol A. Flores, US public housing in the 1930s: The first projects in Atlanta, Georgia]

- 1 2 3 4 5 Charles Forrest Palmer, Adventures of a Slum Fighter

- ↑ Life magazine, December 26, 1938