Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the seat of government of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Charlotte. At the 2020 census, the city's population was 46,553. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the City of Charlottesville with Albemarle County for statistical purposes, bringing its population to approximately 160,000. Charlottesville is the heart of the Charlottesville metropolitan area, which includes Albemarle, Buckingham, Fluvanna, Greene, and Nelson counties.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P. Huntington, it reached from Virginia's capital city of Richmond to the Ohio River by 1873, where the railroad town of Huntington, West Virginia, was named for him.

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for 206 miles (332 km) to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railroad began near the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad's line and expanded westward to Orange County, reaching Gordonsville by 1840. In 1849, the Blue Ridge Railroad was chartered to construct a line over the Blue Ridge Mountains for the Louisa Railroad which reached the base of the Blue Ridge in 1852. After a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, the Louisa Railroad was allowed to expand eastward from a point near Doswell to Richmond.

The San Diego Electric Railway (SDERy) was a mass transit system in Southern California, United States, using 600 volt DC streetcars and buses.

New York State Railways was a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad that controlled several large city streetcar and electric interurban systems in upstate New York. It included the city transit lines in Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Oneida and Rome, plus various interurban lines connecting those cities. New York State Railways also held a 50% interest in the Schenectady Railway Company, but it remained a separate independent operation. The New York Central took control of the Rochester Railway Company, the Rochester and Eastern Rapid Railway and the Rochester and Sodus Bay Railway in 1905, and the Mohawk Valley Company was formed by the railroad to manage these new acquisitions. New York State Railways was formed in 1909 when the properties controlled by the Mohawk Valley Company were merged. In 1912 it added the Rochester and Suburban Railway, the Syracuse Rapid Transit Railway, the Oneida Railway, and the Utica and Mohawk Valley Railway. The New York Central Railroad was interested in acquiring these lines in an effort to control the competition and to gain control of the lucrative electric utility companies that were behind many of these streetcar and interurban railways. Ridership across the system dropped through the 1920s as operating costs continued to rise, coupled with competition from better highways and private automobile use. New York Central sold New York State Railways in 1928 to a consortium led by investor E. L. Phillips, who was looking to gain control of the upstate utilities. Phillips sold his stake to Associated Gas & Electric in 1929, and the new owners allowed the railway bonds to default. New York State Railways entered receivership on December 30, 1929. The company emerged from receivership in 1934, and local operations were sold off to new private operators between 1938 and 1948.

Streetcars in Washington, D.C. transported people across the city and region from 1862 until 1962.

Transportation in Richmond, Virginia and its immediate surroundings include land, sea and air modes. This article includes the independent city and portions of the contiguous counties of Henrico and Chesterfield. While almost all of Henrico County would be considered part of the Richmond area, southern and eastern portions of Chesterfield adjoin the three smaller independent cities of Petersburg, Hopewell, and Colonial Heights, collectively commonly called the Tri-Cities area. A largely rural section of southwestern Chesterfield may be considered not a portion of either suburban area.

The Los Angeles Railway was a system of streetcars that operated in Central Los Angeles and surrounding neighborhoods between 1895 and 1963. The system provided frequent local services which complemented the Pacific Electric "Red Car" system's largely commuter-based interurban routes. The company carried many more passengers than the Red Cars, which served a larger and sparser area of Los Angeles.

The Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) was operator of the street railway system of Chicago, Illinois, from 1913 to 1947. The firm is a predecessor of today's publicly owned operator, the Chicago Transit Authority.

Streetcars and interurbans operated in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., between 1890 and 1962.

The Capital Traction Company was the smaller of the two major street railway companies in Washington, D.C., in the early 20th century.

The Washington Railway and Electric Company (WRECo) was the larger of the two major streetcar companies in Washington, D.C., and its Maryland suburbs in the early decades of the 20th century.

Virginia Beach, Virginia's development is tied to the establishment of a transportation infrastructure that allowed access to the Atlantic shoreline.

The Chesapeake Beach Railway (CBR), now defunct, was an American railroad of southern Maryland and Washington, D.C., built in the 19th century. The CBR ran 27.629 miles from Washington, D.C., on tracks laid by the Southern Maryland Railroad and its own single track through Maryland farm country to a resort at Chesapeake Beach. The construction of the railway was overseen by Otto Mears, a Colorado railroad builder, who planned a shoreline resort with railroad service from Washington and Baltimore. It served Washington and Chesapeake Beach for almost 35 years, but closed amid the Great Depression and the rise of the automobile. The last train left the station on April 15, 1935. Parts of the right-of-way are now used for roads and a future rail trail.

The Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway (WB&A) was an American railroad of central Maryland and Washington, D.C., built in the 19th and 20th century. The WB&A absorbed two older railroads, the Annapolis and Elk Ridge Railroad and the Baltimore & Annapolis Short Line, and added its own electric streetcar line between Baltimore and Washington. It was built by a group of Cleveland, Ohio, electric railway entrepreneurs to serve as a high-speed, showpiece line using the most advanced technology of the time. It served Washington, Baltimore, and Annapolis, Maryland, for 27 years before the Great Depression and the rise of the automobile forced an end to passenger service during the economic pressures of the 1930s depression southwest to Washington from Baltimore & west from Annapolis in 1935. Only the Baltimore & Annapolis portion between the state's largest city and its state capital continued to operate electric rail cars for another two decades, replaced by a bus service during the late 1950s into 1968. Today, parts of the right-of-way are used for the light rail line, rail trail for hiking - biking trails, and roads through Anne Arundel County.

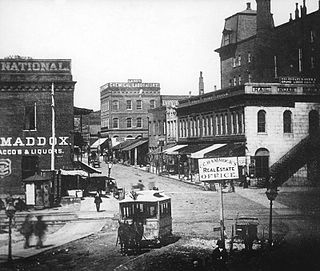

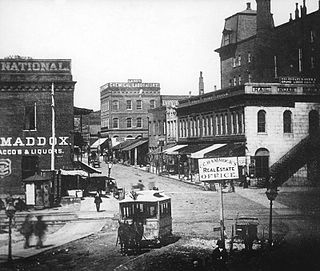

Streetcars originally operated in Atlanta downtown and into the surrounding areas from 1871 until the final line's closure in 1949.

The Fast Flying Virginian (FFV) was a named passenger train of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway.

The Greenwood Tunnel is a historic railroad tunnel constructed in 1853 by Claudius Crozet during the construction of the Blue Ridge Railroad. The tunnel was the easternmost tunnel in a series of four tunnels that were essential for crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. Located near Greenwood in Albemarle County, Virginia, the tunnel was used by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) until its abandonment in 1944.

The Rochester Railway Company operated a streetcar transit system throughout the city of Rochester from 1890 until its acquisition by Rochester Transit Corp. in 1938. Formed by a group of Pittsburgh investors, the Rochester Railway Company purchased the Rochester City & Brighton Railroad in 1890, followed by a lease of the Rochester Electric Railway in 1894. The Rochester and Suburban Railway was leased in 1905, extending the system's reach to Irondequoit and Sea Breeze. Rochester Railways was acquired by the Mohawk Valley Company, a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad set up to take control of electric railways in its territory. In 1909 the holdings of the Mohawk Valley Company were consolidated as the New York State Railways.