The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the first and oldest specialised agencies of the UN. The ILO has 187 member states: 186 out of 193 UN member states plus the Cook Islands. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with around 40 field offices around the world, and employs some 3,381 staff across 107 nations, of whom 1,698 work in technical cooperation programmes and projects.

Eswatini, formally the Kingdom of Eswatini and also known by its former official name Swaziland, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its north, west, south, and southeast. At no more than 200 km (120 mi) north to south and 130 km (81 mi) east to west, Eswatini is one of the smallest countries in Africa; despite this, its climate and topography are diverse, ranging from a cool and mountainous highveld to a hot and dry lowveld.

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide, although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in the Americas.

Mswati III is Ngwenyama (King) of Eswatini and head of the Swazi royal family.

Trafficking of children is a form of human trafficking and is defined by the United Nations as the "recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, and/or receipt" kidnapping of a child for the purpose of slavery, forced labour, and exploitation. This definition is substantially wider than the same document's definition of "trafficking in persons". Children may also be trafficked for adoption.

Child labour in Botswana is defined as the exploitation of children through any form of work which is harmful to their physical, mental, social and moral development. Child labour in Botswana is characterised by the type of forced work at an associated age, as a result of reasons such as poverty and household-resource allocations. child labour in Botswana is not of higher percentage according to studies. The United States Department of Labor states that due to the gaps in the national frameworks, scarce economy, and lack of initiatives, “children in Botswana engage in the worst forms of child labour”. The International Labour Organization is a body of the United Nations which engages to develop labour policies and promote social justice issues. The International Labour Organization (ILO) in convention 138 states the minimum required age for employment to act as the method for "effective abolition of child labour" through establishing minimum age requirements and policies for countries when ratified. Botswana ratified the Minimum Age Convention in 1995, establishing a national policy allowing children at least fourteen-years old to work in specified conditions. Botswana further ratified the ILO's Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, convention 182, in 2000.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Eswatini have limited legal rights. According to Rock of Hope, a Swati LGBT advocacy group, "there is no legislation recognising LGBTIs or protecting the right to a non-heterosexual orientation and gender identity and as a result [LGBT people] cannot be open about their orientation or gender identity for fear of rejection and discrimination". Homosexuality is illegal in Eswatini, though this law is in practice unenforced. According to the 2021 Human Rights Practices Report from the US Department of State, "there has never been an arrest or prosecution for consensual same-sex conduct."

Eswatini–United States relations are bilateral relations between Eswatini and the United States.

Education in Eswatini includes pre-school, primary, secondary and high schools, for general education and training (GET), and universities and colleges at tertiary level.

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions. As of 2016, Eswatini had the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).

Child labour in Bangladesh is significant, with 4.7 million children aged 5 to 14 in the work force in 2002-03. Out of the child labourers engaged in the work force, 83% are employed in rural areas and 17% are employed in urban areas. Child labour can be found in agriculture, poultry breeding, fish processing, the garment sector and the leather industry, as well as in shoe production. Children are involved in jute processing, the production of candles, soap and furniture. They work in the salt industry, the production of asbestos, bitumen, tiles and ship breaking.

Prostitution in Eswatini is illegal, the anti-prostitution laws dating back to 1889, when the country Eswatini was a protectorate of South Africa. Law enforcement is inconsistent, particularly near industrial sites and military bases. Police tend to turn a blind eye to prostitution in clubs. There are periodic clamp-downs by the police.

A significant proportion of children in India are engaged in child labour. In 2011, the national census of India found that the total number of child labourers, aged [5–14], to be at 10.12 million, out of the total of 259.64 million children in that age group. The child labour problem is not unique to India; worldwide, about 217 million children work, many full-time.

Eswatini, Africa's last remaining absolute monarchy, was rated by Freedom House from 1972 to 1992 as "Partly Free"; since 1993, it has been considered "Not Free". During these years the country's Freedom House rating for "Political Rights" has slipped from 4 to 7, and "Civil Liberties" from 2 to 5. Political parties have been banned in Eswatini since 1973. A 2011 Human Rights Watch report described the country as being "in the midst of a serious crisis of governance", noting that "[y]ears of extravagant expenditure by the royal family, fiscal indiscipline, and government corruption have left the country on the brink of economic disaster". In 2012, the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) issued a sharp criticism of Eswatini's human-rights record, calling on the Swazi government to honor its commitments under international law in regards to freedom of expression, association, and assembly. HRW notes that owing to a 40% unemployment rate and low wages that oblige 80% of Swazis to live on less than US$2 a day, the government has been under "increasing pressure from civil society activists and trade unionists to implement economic reforms and open up the space for civil and political activism" and that dozens of arrests have taken place "during protests against the government's poor governance and human rights record".

Eswatini is a source, destination, and transit country for women and children subjected to trafficking in persons, specifically commercial sexual exploitation, involuntary domestic servitude, and forced labor in agriculture. Swazi girls, particularly orphans, are subjected to commercial sexual exploitation and involuntary domestic servitude in the cities of Mbabane and Manzini, as well as in South Africa and Mozambique.

Child labour in Pakistan is the employment of children to work in Pakistan, which causes them mental, physical, moral and social harm. Child labour takes away the education from children. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that in the 1990s, 11 million children were working in the country, half of whom were under age ten. In 1996, the median age for a child entering the work force was seven, down from eight in 1994. It was estimated that one quarter of the country's work force was made up of children. Child labor stands out as a significant issue in Pakistan, primarily driven by poverty. The prevalence of poverty in the country has compelled children to engage in labor, as it has become necessary for their families to meet their desired household income level, enabling them to afford basic necessities like butter and bread.

Child labour refers to the full-time employment of children under a minimum legal age. In 2003, an International Labour Organization (ILO) survey reported that one in every ten children in the capital above the age of seven was engaged in child domestic labour. Children who are too young to work in the fields work as scavengers. They spend their days rummaging in dumps looking for items that can be sold for money. Children also often work in the garment and textile industry, in prostitution, and in the military.

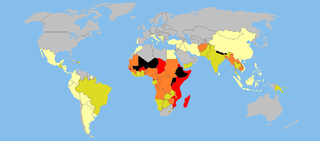

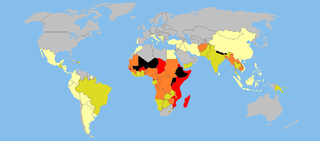

Child labour in Africa is generally defined based on two factors: type of work and minimum appropriate age of the work. If a child is involved in an activity that is harmful to his/her physical and mental development, he/she is generally considered as a child labourer. That is, any work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. Appropriate minimum age for each work depends on the effects of the work on the physical health and mental development of children. ILO Convention No. 138 suggests the following minimum age for admission to employment under which, if a child works, he/she is considered as a child laborer: 18 years old for hazardous works, and 13–15 years old for light works, although 12–14 years old may be permitted for light works under strict conditions in very poor countries. Another definition proposed by ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Program on Child Labor (SIMPOC) defines a child as a child labourer if he/she is involved in an economic activity, and is under 12 years old and works one or more hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least 14 hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least one hour per week in activities that are hazardous, or is 17 or under and works in an "unconditional worst form of child labor".

Sibonelo Mngometulu, known as Inkhosikati LaMbikiza, is the senior queen consort and third wife of King Mswati III of Eswatini. Sibonelo married Mswati III in 1986, becoming the first wife he personally chose to marry, following two ceremonious marriages. She is the mother of Princess Sikhanyiso Dlamini and Prince Lindani Dlamini.

Child Labor in Saudi Arabia is the employing of children for work that deprives children of their childhood, dignity, potential, and that is harmful to a child’s physical and mental development.