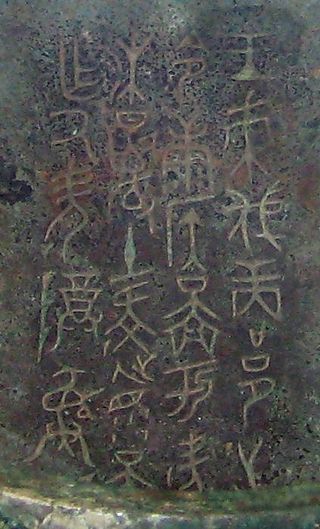

Illustrations

In classical Chinese

The function of a Chinese particle depends on its position in the sentence and on context. In many cases, the character used for a particle is a phonetic loan; therefore, the same particle could be written with different characters that share the same sound. For example, qí/jī (其, which originally represented the word jī "winnowing basket", now represented by the character 箕), a common particle in classical Chinese, has, among others, various meaning as listed below.

The following list provides examples of the functions of particles in Classical Chinese. Classical Chinese refers to the traditional style of written Chinese that is modelled on the Classics, such as Confucius's Analects . Thus, its usage of particles differs from that of modern varieties of Chinese. [7]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2011) |

| Preceding syntactic element | Example sentence | Translation |

|---|---|---|

qí/jī 其 | Can have various functions depending on context. | |

| third-person possessive adjective: his/her/its/their | Gōng yù shàn qí shì, bì xiān lì qí qì. 工欲善其事,必先利其器。 | A workman who wants to do his job well has to sharpen his tools first. |

| demonstrative adjective: that/those | Yǐ qí rén zhī dào, huán zhì qí rén zhī shēn. 以其人之道,還治其人之身。 | Punish that person (someone) with his very own tricks. |

| suffix before adjective or verb | Běifēng qí liáng, yǔ xuě qí pāng. 北風其涼,雨雪其雱。 | The northern wind is cool; the snow falls heavily. |

| to express doubt, uncertainty | Wú qí huán yě. Jūn qí wèn zhū shuǐ bīn. 吾其還也。 君其問諸水濱。 | I had better go. You have to go to the riverside to make an inquiry, I'm afraid. |

| to express hope, command | Wúzi qí wú fèi xiān jūn zhī gōng! 吾子其無廢先君之功! | Boy, don't ruin the accomplishment of your father! |

| to form a rhetorical question | Yù jiāzhī zuì, qí wú cí hu? 欲加之罪,其無辭乎? | How could we fail to find words, when we want to accuse someone? |

zhī 之 | Possessive marker | |

| personal pronoun | Hérén zhī jiàn 何人之劍 | Whose sword is this? |

| proper noun | Dōngfāng zhī guāng 東方之光 | The light of the East |

yǔ 与/與 | Translates to: "and" (conjunction); "with" or "as with" (preposition). | |

yě 也 | Emphatic final particle. | |

ér 而 | Conjunction | |

hu 乎 | Can have various functions depending on context.

| |

| Phrases: question | Bù yì jūnzǐ hu 不亦君子乎 | Is this not the mark of a gentleman? |

In modern varieties of Chinese

Baihua

Written vernacular Chinese (白话; 白話; báihuà), refers to written Chinese that is based on the vernacular language used during the period between imperial China and the early 20th century. [8] The use of particles in vernacular Chinese differs from that of Classical Chinese, as can be seen in the following examples. Usage of particles in modern Standard Chinese is similar to that illustrated here.

| Preceding syntactic element | Example sentence | Translation |

|---|---|---|

ba 吧 | Emphatic final particle. Indicates a suggestion, or softens a command into a question. Equivalent to using a question tag like "aren't you?" or making a suggestion in the form of "let's (do something)". | |

| Verbs | Wǒmen zǒu ba. 我們走吧。 | Let's go. |

de 的 | Used as a possession indicator, topic marker, nominalization. Vernacular Chinese equivalent of Classical 之. | |

| Nominal (noun or pronoun): possession | Zhāngsān de chē 張三的車 | Zhangsan's car. |

| Adjective (stative verb): description | Piàoliang de nǚhái 漂亮的女孩 | Pretty girl. |

| Verbal phrase: relativization (creates a relative clause) | Tiàowǔ de nǚhái 跳舞的女孩 | The girl who dances (dancing girl) |

děng 等 | Translates to: "for example, things like, such as, etc., and so on". Used at the end of a list. | |

| Nouns | Shāngpǐn yǒu diànnǎo, shǒujī, yídòng yìngpán děng děng. 商品有電腦,手機,移動硬盤等等。 | Products include computers, mobile phones, portable hard drives, et cetera. (The second 等 can be omitted) |

gè 個 | Used as a counter, also called a measure word.(general classifier) This is the most commonly used classifier, but anywhere from a few dozen to several hundred classifiers exist in Chinese. | |

| Number | Yī gè xiāngjiāo 一個香蕉 | One banana |

| Yī xiē xiāngjiāo 一些香蕉 | Some bananas | |

| Note: general classifier | All Chinese classifiers generally have the same usage, but different nouns use different measure words in different situations. | ie: 人(rén; person) generally uses 個(gè), but uses 位(wèi) for polite situations, 班(bān) for groups of people, and 輩(bèi) for generations of people, while 花(huā; flower) uses 支(zhī) for stalks of flowers and 束(shù) for bundles of flowers. |

hái 還 | Translates to: "also", "even", "still" | |

| Verbs | Wǒmen hái yǒu wèixīng píndào! 我們還有衛星頻道! | We also have satellite television channels! |

| Verbs | Tā hái zài shuìjiào ne. 他還在睡覺呢。 | He is still sleeping. |

hé 和 | Translates to: "and" (conjunction); "with" or "as with" (preposition). Vernacular Chinese equivalent of Classical 與. | |

| Nouns: conjunction | Zhāng Sān hé Lǐ Sì shì wǒmen zuì cōngmíng de xuéshēng. 張三和李四是我們最聰明的學生。 | Zhang San and Li Si are our most intelligent students. |

kě 可 | Translates to: "could", "-able" | |

| Verbs | Nǐ kěyǐ huí jiāle. 你可以回家了。 | You can go home now. |

| Verbs | Kě'ài 可愛 | Loveable (i.e. cute) |

le 了 | Used to indicate a completed action. Within informal language, can be alternatively replaced with 啦 la or 嘍 lou. | |

| Action | Tā zǒu le 他走了 | He has gone. |

ma 嗎 | Used as a question denominator. | |

| Phrases: question | Nǐ jiǎng gúoyǔ ma? 你講國語嗎? | Do you speak Mandarin? |

shì 是 | Used as the copula "to be"; as a topic marker. | |

| Nouns | Zhège nǚhái shì měiguó rén. 這個女孩是美國人。 | This girl is an American. |

yě 也 | Translates to: "also" | |

| Nouns | Wǒ yěshì xuéshēng. 我也是學生。 | I am also a student. |

zhe 著 | Used to indicate a continuing action. | |

| Action | Tā shuìzhejiào shí yǒurén qiāomén 他睡着覺時有人敲門 | Someone knocked while he was sleeping. |

zhǐ 只 | Translates to: "only, just" | |

| Nouns | Zhǐyǒu chéngrén kěyǐ rù nèi. 只有成人可以入内。 | Only adults are permitted to enter. |