Related Research Articles

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement concluded by sovereign states in international law. International organizations can also be party to an international treaty.

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collude with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers to limit competition and increase prices by creating artificial shortages through low production quotas, stockpiling, and marketing quotas. Cartels can be vertical or horizontal but are inherently unstable due to the temptation to defect and falling prices for all members. Additionally, advancements in technology or the emergence of substitutes may undermine cartel pricing power, leading to the breakdown of the cooperation needed to sustain the cartel. Cartels are usually associations in the same sphere of business, and thus an alliance of rivals. Most jurisdictions consider it anti-competitive behavior and have outlawed such practices. Cartel behavior includes price fixing, bid rigging, and reductions in output. The doctrine in economics that analyzes cartels is cartel theory. Cartels are distinguished from other forms of collusion or anti-competitive organization such as corporate mergers.

A syndicate is a self-organizing group of individuals, companies, corporations or entities formed to transact some specific business, to pursue or promote a shared interest.

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust law, anti-monopoly law, and trade practices law; the act of pushing for antitrust measures or attacking monopolistic companies is commonly known as trust busting.

The Phoebus cartel was an international cartel that controlled the manufacture and sale of incandescent light bulbs in much of Europe and North America between 1925–1939. The cartel took over market territories and lowered the useful life of such bulbs, which is commonly cited as an example of planned obsolescence.

The economy of Fascist Italy refers to the economy in the Kingdom of Italy under Fascism between 1922 and 1943. Italy had emerged from World War I in a poor and weakened condition and, after the war, suffered inflation, massive debts and an extended depression. By 1920, the economy was in a massive convulsion, with mass unemployment, food shortages, strikes, etc. That conflagration of viewpoints can be exemplified by the so-called Biennio Rosso.

Paul Friedländer was a German philologist specializing in classical literature.

Ultra-imperialism is a potential, comparatively peaceful phase of capitalism, meaning after or beyond imperialism. It was described mainly by Karl Kautsky. Post-imperialism is sometimes used as a synonym of ultra-imperialism, although it can have distinct meanings.

Since the 18th century Berlin has been an influential musical center in Germany and Europe. First as an important trading city in the Hanseatic League, then as the capital of the electorate of Brandenburg and the Prussian Kingdom, later on as one of the biggest cities in Germany it fostered an influential music culture that remains vital until today. Berlin can be regarded as the breeding ground for the powerful choir movement that played such an important role in the broad socialization of music in Germany during the 19th century.

Michael Altenburg was a German theologian and composer.

Dieter Senghaas is a German social scientist and peace researcher.

State cartel theory is a new concept in the field of international relations theory (IR) and belongs to the group of institutionalist approaches. Up to now the theory has mainly been specified with regard to the European Union (EU), but could be made much more general. Hence state cartel theory should consider all international governmental organizations (IGOs) as cartels made up by states.

Super-imperialism is a Marxist term with two possible meanings. It can refer:

Dieter Mahncke is a scholar of foreign policy and security studies, and Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Professor Emeritus of European Foreign Policy and Security Studies at the College of Europe. He is the author of books and articles on European security, arms control, German foreign policy, Berlin, US-European relations and South Africa.

The history of United States antitrust law is generally taken to begin with the Sherman Antitrust Act 1890, although some form of policy to regulate competition in the market economy has existed throughout the common law's history. Although "trust" had a technical legal meaning, the word was commonly used to denote big business, especially a large, growing manufacturing conglomerate of the sort that suddenly emerged in great numbers in the 1880s and 1890s. The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 began a shift towards federal rather than state regulation of big business. It was followed by the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, and the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950.

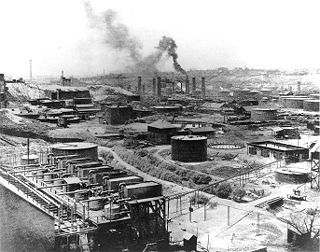

The Rhenish-Westphalian Coal Syndicate was a cartel established in 1893 in Essen bringing together the major coal producers in the Ruhr.

The Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy was a cartel of iron smelters seated in Longwy, a town in Lorraine, department Meurthe-et-Moselle, France. In a narrower sense of the term, the ‘Comptoir de Longwy’ was only the ‘’sales agency’’ of the respectively underlying cartel, which also enclosed its member firms and possible other cartel organs. As a legal entity, the Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy existed from December 10, 1876, to February 1, 1921. It should not be mixed up with the Aciéries de Longwy, which was temporarily a member firm of the cartel not earlier than 1880 and survived the cartel up to 1978.

Holm Arno Leonhardt is a German scientist in the fields of International Relations and economic history, especially in the realm of cartel history and theory. He was born in Manila (Philippines) the son of Brigitte and Arno Leonhardt. Arno became a German expatriate since 1930, moving up the career ladder from accountant to vice director in the branch office of an American paper machine company in Manila. Brigitte came from a liberal merchant family in Saxony (Germany) holding critical distance to the Nazi regime.

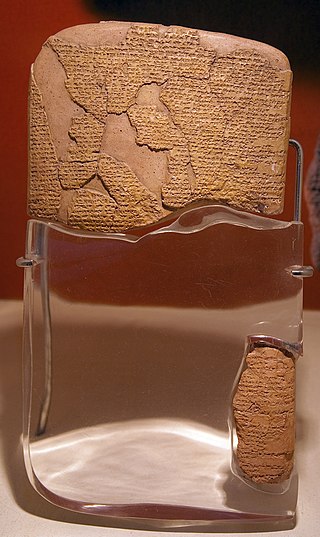

Cartel theory is usually understood as the doctrine of economic cartels. However, since the concept of 'cartel' does not have to be limited to the field of the economy, doctrines on non-economic cartels are conceivable in principle. Such exist already in the form of the state cartel theory and the cartel party theory. For the pre-modern cartels, which existed as rules for tournaments, duels and court games or in the form of inter-state fairness agreements, there was no scientific theory. Such has developed since the 1880s for the scope of the economy, driven by the need to understand and classify the mass emergence of entrepreneurial cartels. Within the economic cartel theory, one can distinguish a classical and a modern phase. The break between the two was set through the enforcement of a general cartel ban after Second World War by the US government.

Cartel seats as monuments were the headquarters or other premises of historical, no longer existing cartels in the sense of a group of cooperating, but potentially also rival enterprises. Often, these associations had been syndicate cartels, being an advanced form of entrepreneurial combination because of their tight organization with a common sales agency. The cartel buildings had been used for secretariats, meeting rooms, sales offices, advertising agencies, research departments and further more. Many such historical buildings can still be found in Europe and the United States.

References

- ↑ Holm A. Leonhardt: Kartelltheorie und Internationale Beziehungen. Theoriegeschichtliche Studien, Hildesheim 2013, p. 144-145.

- ↑ Holm A. Leonhardt: Kartelltheorie und Internationale Beziehungen. Theoriegeschichtliche Studien, Hildesheim 2013, p. 146-155.

- ↑ Jeffrey R. Fear: Cartels. In: Geoffrey Jones; Jonathan Zeitlin (ed.): The Oxford handbook of business history. Oxford: Univ. Press, 2007, p. 271.

- ↑ Holm A. Leonhardt: Kartelltheorie und Internationale Beziehungen. Theoriegeschichtliche Studien, Hildesheim 2013, p. 164-165.

- ↑ Liefmann, Robert: Cartels, Concerns and Trusts, Ontario 2001 [London 1932], p. 267.

- ↑ Hausleiter, Leo (1932): Revolution der Weltwirtschaft. München, p. 200.

- ↑ Liefmann, Robert: Cartels, Concerns and Trusts, Ontario 2001 [London 1932], p. 268.