| Daniel 2 | |

|---|---|

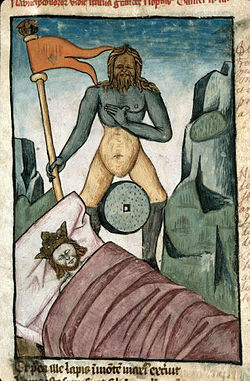

Nebuchadnezzar's dream: the composite statue (France, 15th century) | |

| Book | Book of Daniel |

| Category | Ketuvim |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 27 |

Daniel 2 (the second chapter of the Book of Daniel) tells how Daniel related and interpreted a dream of Nebuchadnezzar II, king of Babylon. In his night dream, the king saw a gigantic statue made of four metals, from its head of gold to its feet of mingled iron and clay; as he watched, a stone "not cut by human hands" destroyed the statue and became a mountain filling the whole world. Daniel explained to the king that the statue represented four successive kingdoms beginning with Babylon, while the stone and mountain signified a kingdom established by God which would never be destroyed nor given to another people. Nebuchadnezzar then acknowledges the supremacy of Daniel's God and raises him to high office in Babylon. [1]

Contents

- Biblical narrative

- Composition and structure

- Book of Daniel

- Daniel 2

- Genre and themes

- Genre

- Themes

- Interpretation

- Overview: dreams in the ancient world

- The four world kingdoms and the rock

- Christian eschatological readings

- See also

- References

- Citations

- Bibliography

Chapter 2 in its present form dates from no earlier than the first decades of the Seleucid Empire (312–63 BCE), but its roots may reach back to the Fall of Babylon (539 BCE) and the rise of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE). [2] The overall theme of the Book of Daniel is God's sovereignty over history. [3] On the human level Daniel is set against the Babylonian magicians who fail to interpret the king's dream, but the cosmic conflict is between the God of Israel and the false Babylonian gods. [4] What counts is not Daniel's human gifts, nor his education in the arts of divination, but "Divine Wisdom" and the power that belongs to God alone, as Daniel indicates when he urges his companions to seek God's mercy for the interpretation of the king's dreams. [5]