An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ACID, for "anode current into device". The direction of conventional current in a circuit is opposite to the direction of electron flow, so electrons flow from the anode of a galvanic cell, into an outside or external circuit connected to the cell. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a "+" is the cathode.

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic CCD for Cathode Current Departs. A conventional current describes the direction in which positive charges move. Electrons have a negative electrical charge, so the movement of electrons is opposite to that of the conventional current flow. Consequently, the mnemonic cathode current departs also means that electrons flow into the device's cathode from the external circuit. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a + (plus) is the cathode.

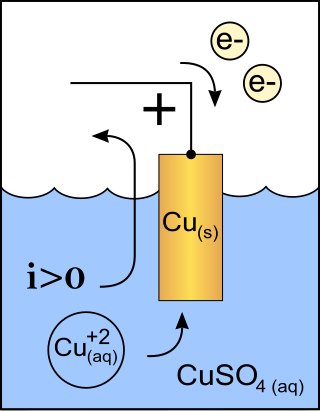

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve electrons moving via an electronically-conducting phase between electrodes separated by an ionically conducting and electronically insulating electrolyte.

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve, or tube, is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

A Tesla coil is an electrical resonant transformer circuit designed by inventor Nikola Tesla in 1891. It is used to produce high-voltage, low-current, high-frequency alternating-current electricity. Tesla experimented with a number of different configurations consisting of two, or sometimes three, coupled resonant electric circuits.

An electrometer is an electrical instrument for measuring electric charge or electrical potential difference. There are many different types, ranging from historical handmade mechanical instruments to high-precision electronic devices. Modern electrometers based on vacuum tube or solid-state technology can be used to make voltage and charge measurements with very low leakage currents, down to 1 femtoampere. A simpler but related instrument, the electroscope, works on similar principles but only indicates the relative magnitudes of voltages or charges.

In electrical engineering, ground or earth may be a reference point in an electrical circuit from which voltages are measured, a common return path for electric current, or a direct physical connection to the Earth.

In electromagnetism and electronics, electromotive force is an energy transfer to an electric circuit per unit of electric charge, measured in volts. Devices called electrical transducers provide an emf by converting other forms of energy into electrical energy. Other electrical equipment also produce an emf, such as batteries, which convert chemical energy, and generators, which convert mechanical energy. This energy conversion is achieved by physical forces applying physical work on electric charges. However, electromotive force itself is not a physical force, and ISO/IEC standards have deprecated the term in favor of source voltage or source tension instead.

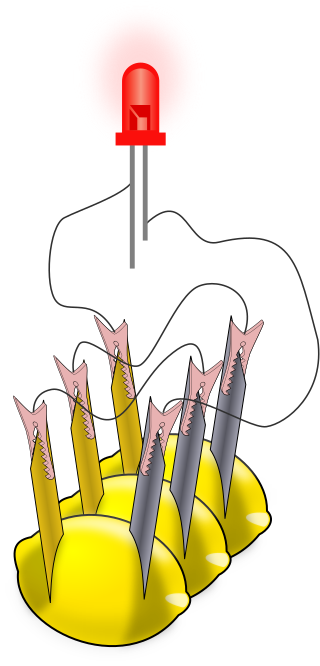

A lemon battery is a simple battery often made for the purpose of education. Typically, a piece of zinc metal and a piece of copper are inserted into a lemon and connected by wires. Power generated by reaction of the metals is used to power a small device such as a light-emitting diode (LED).

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Branly and adapted by other physicists and inventors over the next ten years. The device consists of a tube or capsule containing two electrodes spaced a small distance apart with loose metal filings in the space between. When a radio frequency signal is applied to the device, the metal particles would cling together or "cohere", reducing the initial high resistance of the device, thereby allowing a much greater direct current to flow through it. In a receiver, the current would activate a bell, or a Morse paper tape recorder to make a record of the received signal. The metal filings in the coherer remained conductive after the signal (pulse) ended so that the coherer had to be "decohered" by tapping it with a clapper actuated by an electromagnet, each time a signal was received, thereby restoring the coherer to its original state. Coherers remained in widespread use until about 1907, when they were replaced by more sensitive electrolytic and crystal detectors.

A telluric current, or Earth current, is an electric current that flows underground or through the sea, resulting from natural and human-induced causes. These currents have extremely low frequency and traverse large areas near or at the Earth's surface. The Earth's crust and mantle are host to telluric currents, with around 32 mechanisms generating them, primarily geomagnetically induced currents caused by changes in the Earth's magnetic field due to solar wind interactions with the magnetosphere or solar radiation's effects on the ionosphere. These currents exhibit diurnal patterns, flowing towards the Sun during the day and towards the poles at night.

Wireless power transfer (WPT), wireless power transmission, wireless energy transmission (WET), or electromagnetic power transfer is the transmission of electrical energy without wires as a physical link. In a wireless power transmission system, an electrically powered transmitter device generates a time-varying electromagnetic field that transmits power across space to a receiver device; the receiver device extracts power from the field and supplies it to an electrical load. The technology of wireless power transmission can eliminate the use of the wires and batteries, thereby increasing the mobility, convenience, and safety of an electronic device for all users. Wireless power transfer is useful to power electrical devices where interconnecting wires are inconvenient, hazardous, or are not possible.

A plasma ball, plasma globe, or plasma lamp is a clear glass container filled with noble gases, usually a mixture of neon, krypton, and xenon, that has a high-voltage electrode in the center of the container. When voltage is applied, a plasma is formed within the container. Plasma filaments extend from the inner electrode to the outer glass insulator, giving the appearance of multiple constant beams of colored light. Plasma balls were popular as novelty items in the 1980s.

An earthing system or grounding system (US) connects specific parts of an electric power system with the ground, typically the Earth's conductive surface, for safety and functional purposes. The choice of earthing system can affect the safety and electromagnetic compatibility of the installation. Regulations for earthing systems vary among countries, though most follow the recommendations of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Regulations may identify special cases for earthing in mines, in patient care areas, or in hazardous areas of industrial plants.

Electrochemistry, a branch of chemistry, went through several changes during its evolution from early principles related to magnets in the early 16th and 17th centuries, to complex theories involving conductivity, electric charge and mathematical methods. The term electrochemistry was used to describe electrical phenomena in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In recent decades, electrochemistry has become an area of current research, including research in batteries and fuel cells, preventing corrosion of metals, the use of electrochemical cells to remove refractory organics and similar contaminants in wastewater electrocoagulation and improving techniques in refining chemicals with electrolysis and electrophoresis.

The Fleming valve, also called the Fleming oscillation valve, was a thermionic valve or vacuum tube invented in 1904 by English physicist John Ambrose Fleming as a detector for early radio receivers used in electromagnetic wireless telegraphy. It was the first practical vacuum tube and the first thermionic diode, a vacuum tube whose purpose is to conduct current in one direction and block current flowing in the opposite direction. The thermionic diode was later widely used as a rectifier — a device that converts alternating current (AC) into direct current (DC) — in the power supplies of a wide range of electronic devices, until beginning to be replaced by the selenium rectifier in the early 1930s and almost completely replaced by the semiconductor diode in the 1960s. The Fleming valve was the forerunner of all vacuum tubes, which dominated electronics for 50 years. The IEEE has described it as "one of the most important developments in the history of electronics", and it is on the List of IEEE Milestones for electrical engineering.

A lightning rod or lightning conductor is a metal rod mounted on a structure and intended to protect the structure from a lightning strike. If lightning hits the structure, it is most likely to strike the rod and be conducted to ground through a wire, rather passing through the structure, where it could start a fire or cause electrocution. Lightning rods are also called finials, air terminals, or strike termination devices.

This article provides information on the following six methods of producing electric power.

- Friction: Energy produced by rubbing two material together.

- Heat: Energy produced by heating the junction where two unlike metals are joined.

- Light: Energy produced by light being absorbed by photoelectric cells, or solar power.

- Chemical: Energy produced by chemical reaction in a voltaic cell, such as an electric battery.

- Pressure: Energy produced by compressing or decompressing specific crystals.

- Magnetism: Energy produced in a conductor that cuts or is cut by magnetic lines of force.