Colonel William Henry Sykes, FRS was an English naturalist who served with the British military in India and was specifically known for his work with the Indian Army as a politician, Indologist and ornithologist. One of the pioneers of the Victorian statistical movement, a founder of the Royal Statistical Society, he conducted surveys and examined the efficiency of army operation. Returning from service in India, he became a director of the East India Company and a member of parliament representing Aberdeen.

John Gould was an English ornithologist who published monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, Henry Constantine Richter, Joseph Wolf and William Matthew Hart. He has been considered the father of bird study in Australia and the Gould League in Australia is named after him. His identification of the birds now nicknamed "Darwin's finches" played a role in the inception of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Gould's work is referenced in Charles Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species.

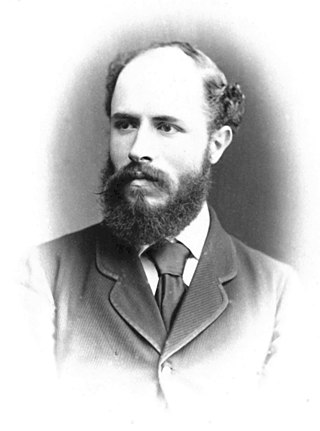

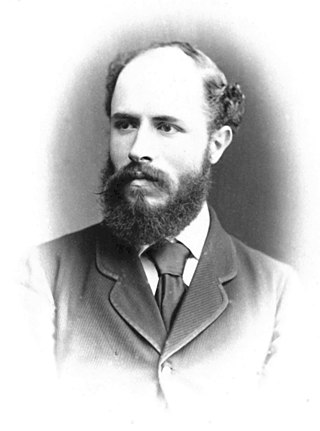

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS was a British political reformer, ornithologist, civil servant and botanist who worked in British India. He supported the idea of self-governance by Indians and founded the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hume has been called "the Father of Indian Ornithology" and, by those who found him dogmatic, "the Pope of Indian Ornithology".

William Elford Leach FRS was an English zoologist and marine biologist.

Robert Swinhoe FRS was an English diplomat and naturalist who worked as a Consul in Taiwan. He catalogued many Southeast Asian birds, and several, such as Swinhoe's pheasant, are named after him.

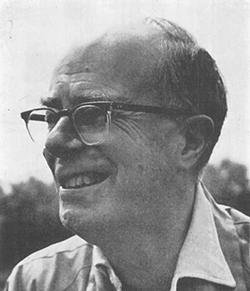

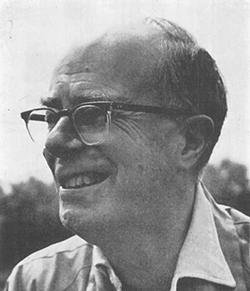

David Lambert Lack FRS was a British evolutionary biologist who made contributions to ornithology, ecology, and ethology. His 1947 book, Darwin's Finches, on the finches of the Galapagos Islands was a landmark work as were his other popular science books on Life of the Robin and Swifts in a Tower. He developed what is now known as Lack's Principle which explained the evolution of avian clutch sizes in terms of individual selection as opposed to the competing contemporary idea that they had evolved for the benefit of species. His pioneering life-history studies of the living bird helped in changing the nature of ornithology from what was then a collection-oriented field. He was a longtime director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at the University of Oxford.

Thomas Caverhill Jerdon was an English physician, zoologist and botanist. He was a pioneering ornithologist who described numerous species of birds in India. Several species of plants and birds including Jerdon's baza, Jerdon's leafbird, Jerdon's bushlark, Jerdon's nightjar, Jerdon's courser, Jerdon's babbler and Jerdon's bush chat are named after him.

Brian Houghton Hodgson was a pioneer naturalist and ethnologist working in India and Nepal where he was a British Resident. He described numerous species of birds and mammals from the Himalayas, and several birds were named after him by others such as Edward Blyth. He was a scholar of Newar Buddhism and wrote extensively on a range of topics relating to linguistics and religion. He was an opponent of the British proposal to introduce English as the official medium of instruction in Indian schools.

Jerdon's courser is a nocturnal bird belonging to the pratincole and courser family Glareolidae endemic to India. The bird was discovered by the surgeon-naturalist Thomas C. Jerdon in 1848 but not seen again until its rediscovery in 1986. This courser is a restricted-range endemic found locally in India in the Eastern Ghats of Andhra Pradesh. It is currently known only from the Sri Lankamalleswara Wildlife Sanctuary, where it inhabits sparse scrub forest with patches of bare ground.

James Wood-Mason was an English zoologist. He was the director of the Indian Museum at Calcutta, after John Anderson. He collected marine animals and lepidoptera, but is best known for his work on two other groups of insects, phasmids and mantises.

Louis Fraser was a British zoologist and collector. In his early years, Fraser was curator of the Museum of the Zoological Society of London.

Johann Ludwig (Louis) Gerard Krefft, was an Australian artist, draughtsman, scientist, and natural historian who served as the curator of the Australian Museum for 13 years (1861–1874). He was one of Australia's first and most influential zoologists and palaeontologists.

Some of [Krefft's] observations on animals have not been surpassed and can no longer be equalled because of the spread of settlement.

Mr. Krefft was probably the first man who thoroughly studied the reptiles of Australia.

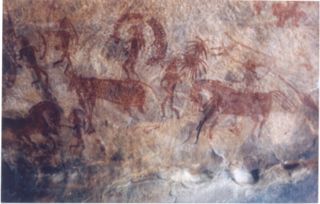

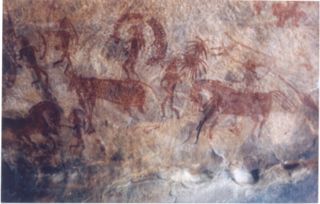

Natural history in the Indian subcontinent has a long heritage with a recorded history going back to the Vedic era. Natural history research in early times included the broad fields of palaeontology, zoology and botany. These studies would today be considered under field of ecology but in former times, such research was undertaken mainly by amateurs, often physicians, civil servants and army officers.

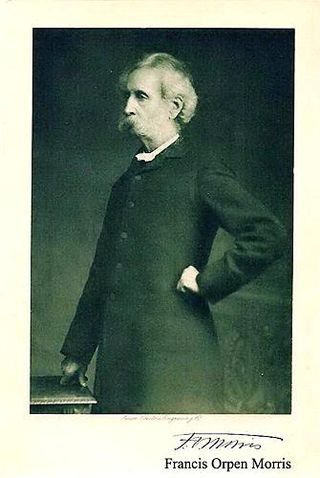

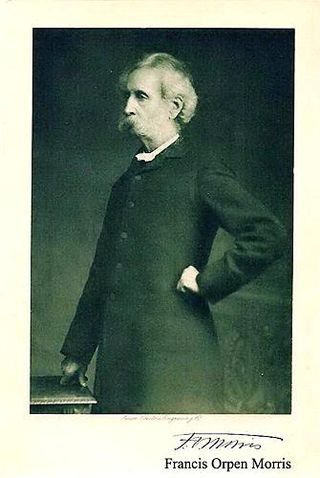

William Thompson was an Irish naturalist celebrated for his founding studies of the natural history of Ireland, especially in ornithology and marine biology. Thompson published numerous notes on the distribution, breeding, eggs, habitat, song, plumage, behaviour, nesting and food of birds. These formed the basis of his four-volume The Natural History of Ireland, and were much used by contemporary and later authors such as Francis Orpen Morris.

Darwin's rhea or the lesser rhea is a large flightless bird, the smaller of the two extant species of rheas. It is found in the Altiplano and Patagonia in South America.

Eumeces blythianus, commonly known as Blyth's skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is native to South Asia.

Edgar Leopold LayardMBOU, was a British diplomat and a naturalist mainly interested in ornithology and to a lesser extent the molluscs. He worked for a significant part of his life in Ceylon and later in South Africa, Fiji and New Caledonia. He studied the zoology of these places and established natural history museums in Sri Lanka and South Africa. Several species of animals are named after him.

Francis Orpen Morris was an Anglo-Irish clergyman, notable as "parson-naturalist" and as the author of many children's books and books on natural history and heritage buildings. He was a pioneer of the movement to protect birds from the plume trade and was a co-founder of the Plumage League. He died on 10 February 1893 and was buried at Nunburnholme, East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

Robert Christopher Tytler was a British soldier, naturalist and photographer. His second wife Harriet C. Tytler is well known for her work in photographing and documenting the monuments of Delhi and for her notes at the time of the 1857 revolt in India. Mt. Harriet in the Andamans is named after her. A species of bird, Tytler's leaf warbler, is named after him.

Le Règne Animal is the most famous work of the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. It sets out to describe the natural structure of the whole of the animal kingdom based on comparative anatomy, and its natural history. Cuvier divided the animals into four embranchements, namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals, and zoophytes.