Mélusine or Melusine or Melusina is a figure of European folklore, a female spirit of fresh water in a holy well or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down. She is also sometimes illustrated with wings, two tails, or both. Her legends are especially connected with the northern and western areas of France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries.

Ruth Sawyer was an American storyteller and a writer of fiction and non-fiction for children and adults. She is best known as the author of Roller Skates, which won the 1937 Newbery Medal. She received the Children's Literature Legacy Award in 1965 for her lifetime achievement in children's literature.

Mhlophe, known as Gcina Mhlophe, is a South African storyteller, writer, playwright, and actress. In 2016, she was listed as one of BBC's 100 Women. She tells her stories in four of South Africa's languages: English, Afrikaans, Zulu and Xhosa, and also helps to motivate children to read.

Mary Louisa Molesworth, néeStewart was an English writer of children's stories who wrote for children under the name of Mrs Molesworth. Her first novels, for adult readers, Lover and Husband (1869) to Cicely (1874), appeared under the pseudonym of Ennis Graham. Her name occasionally appears in print as M. L. S. Molesworth.

"Goldilocks and the Three Bears" is a 19th-century English fairy tale of which three versions exist. The original version of the tale tells of an impudent old woman who enters the forest home of three anthropomorphic bachelor bears while they are away. She eats some of their porridge, sits down on one of their chairs, breaks it, and sleeps in one of their beds. When the bears return and discover her, she wakes up, jumps out of the window, and is never seen again. The second version replaces the old woman with a young, naive, blonde-haired girl named Goldilocks, and the third and by far best-known version replaces the bachelor trio with a family of three. The story has elicited various interpretations and has been adapted to film, opera, and other media. "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" is one of the most popular fairy tales in the English language.

Theresa Tomlinson is an English writer for children, mainly of historical fiction. She advocates giving children "the opportunity to consider many different role models and ways of life, so that they can make up their own minds about what is right for them."

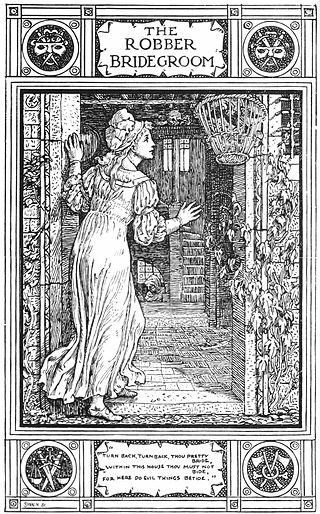

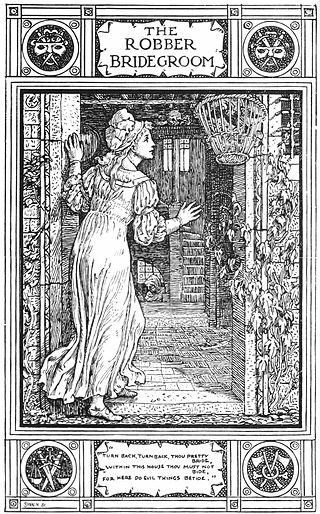

"The Robber Bridegroom" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, tale number 40. Joseph Jacobs included a variant, Mr Fox, in English Fairy Tales, but the original provenance is much older; Shakespeare alludes to the Mr. Fox variant in Much Ado About Nothing, Act 1, Scene 1:

Frances Mary Buss was a British headmistress and a pioneer of girls' education.

The Story Girl is a 1911 novel by Canadian author L. M. Montgomery. It narrates the adventures of a group of young cousins and their friends who live in a rural community on Prince Edward Island, Canada.

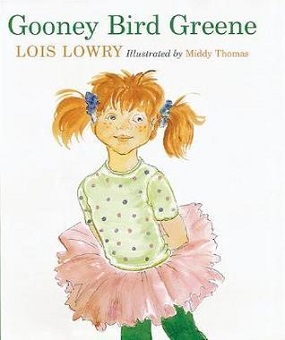

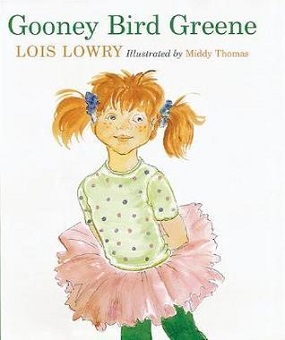

Gooney Bird Greene (2002) is the first of a series of children's novels by Lois Lowry concerning the storytelling abilities of a second-grade girl. It was illustrated by Middy Thomas.

Sarah Doudney was an English fiction writer and poet. She is best known for her children's literature and her hymns.

Joan Margaret Fleming was a British writer of crime and thriller novels. Her novel The Deeds of Dr Deadcert was made into the film Rx Murder (1958), and she won the Gold Dagger award twice, for When I Grow Rich (1962) and Young Man I Think You're Dying (1970).

Julia Corner (1798–1875), also known as Miss Corner, was a British children's educational writer who created Miss Corner's Historical Library.

Frances Jenkins Olcott was the first head librarian of the children's department of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in 1898. She also wrote many children's books and books for those in the profession of providing library service to children and youth.

Matilda Anne Mackarness was an English novelist of the 19th century, primarily writing children's literature.

Margaret Read MacDonald is an American storyteller, folklorist, and award-winning children's book author. She has published more than 65 books, of stories and about storytelling, which have been translated into many languages. She has performed internationally as a storyteller, is considered a "master storyteller", and has been dubbed a "grand dame of storytelling". She focuses on creating "tellable" folktale renditions, which enable readers to share folktales with children easily. MacDonald has been a member of the board of the National Storytelling Network and president of the Children's Folklore Section of the American Folklore Society.

Mary Gould Davis was an American author, librarian, storyteller and editor. She received a Newbery Honor.

The Boy with a Moon on his Forehead is a Bengali folktale collected by Maive Stokes and Lal Behari Day.

Alice Isabel Hazeltine was an American librarian, writer, and editor. She was on the faculty of the School of Library Service at Columbia University, and edited several collections of stories for children and teenagers, published in multiple editions through the twentieth century.

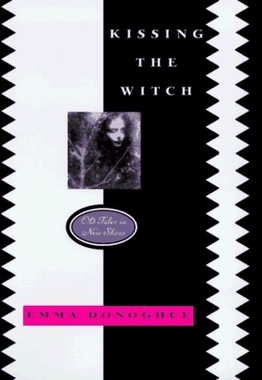

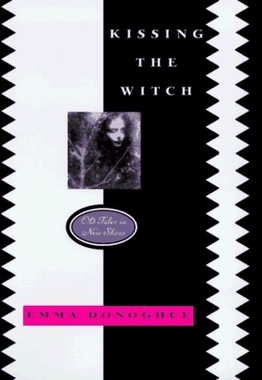

Kissing the Witch is a collection of interconnected fictional short stories written by Irish-Canadian Emma Donoghue. Each of the thirteen stories in the collection is an adaptation of a well-known European fairy tale, with several tales featuring feminist and queer themes. The stories are linked together by a narrative structure where the narrator of the previous story becomes the listener of the story that follows. None of the narrators or characters are named, instead being referred to via epithets and aliases. The book, originally published in 1997 by Hamish Hamilton Ltd., was Donoghue's third published fiction novel and first short story collection. Following its release, Kissing the Witch was translated into Dutch (1997), Catalan (2000), and Italian (2007).