Thomas Stearns Eliot was a poet, essayist and playwright. He was a leading figure in English-language Modernist poetry where he reinvigorated the art through the use of language, writing style, and verse structure. He is also noted for his critical essays, which often re-evaluated long-held cultural beliefs.

Richard Aldington was an English writer and poet. He was an early associate of the Imagist movement. His 50-year writing career covered poetry, novels, criticism and biography. He edited The Egoist, a literary journal, and wrote for The Times Literary Supplement, Vogue, The Criterion, and Poetry. His biography, Wellington (1946), won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's home in Amherst. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, even to leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most of her friendships were based entirely upon correspondence.

John Orley Allen Tate, known professionally as Allen Tate, was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and poet laureate from 1943 to 1944. Among his best known works are the poems "Ode to the Confederate Dead" (1928) and "The Mediterranean" (1933), and his only novel The Fathers (1938). He is associated with New Criticism, the Fugitives and the Southern Agrarians.

"The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" is the first professionally published poem by the American-born British poet T. S. Eliot (1888–1965). The poem relates the varying thoughts of its title character in a stream of consciousness. Eliot began writing the poem in February 1910, and it was first published in the June 1915 issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse at the instigation of fellow American expatriate Ezra Pound. It was later printed as part of a twelve-poem chapbook entitled Prufrock and Other Observations in 1917. At the time of its publication, the poem was considered outlandish, but the poem is now seen as heralding a paradigmatic shift in poetry from late 19th-century Romanticism and Georgian lyrics to Modernism.

Penelope Mary Fitzgerald was a Booker Prize-winning novelist, poet, essayist and biographer from Lincoln, England. In 2008 The Times listed her among "the 50 greatest British writers since 1945". The Observer in 2012 placed her final novel, The Blue Flower, among "the ten best historical novels". A.S. Byatt called her, "Jane Austen’s nearest heir for precision and invention."

Esmé Valerie Eliot was the second wife and later widow of the Nobel prize-winning poet T. S. Eliot. She was a major shareholder in the publishing firm of Faber and Faber Limited and the editor and annotator of a number of books dealing with her late husband's writings.

Lyndall Gordon is a British-based biographical and former academic writer, known for her literary biographies. She is a senior research fellow at St Hilda's College, Oxford.

The Belle of Amherst is a one-woman play by William Luce.

Charlotte Champe Eliot, was an American school teacher, poet, biographer, and social worker. She was the mother of T. S. Eliot, a famous poet, editor and literary critic, wife of Henry Ware Eliot, who ran the Hydraulic Press Brick Company in St. Louis, Missouri, and daughter-in-law of William Greenleaf Eliot, a leading minister in St. Louis and a founder of Washington University in St. Louis.

Richard Benson Sewall was a professor of English at Yale University, and author of the influential works The Life of Emily Dickinson and The Vision of Tragedy.

"Too Much of Nothing" is a song written by Bob Dylan in 1967, first released by him on the album The Basement Tapes (1975).

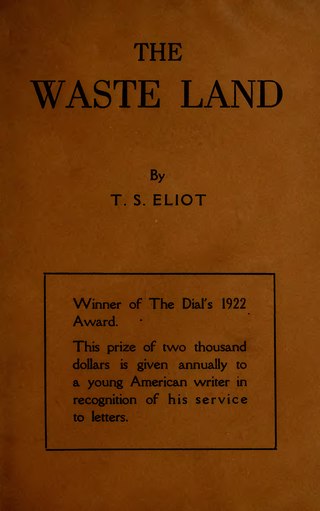

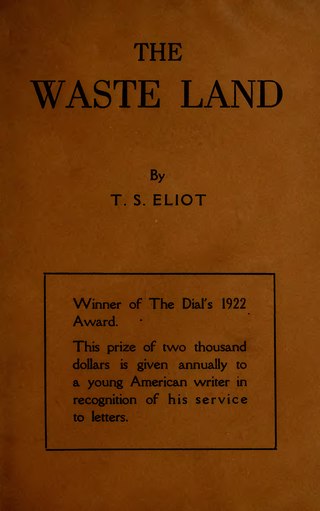

The Waste Land is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important English-language poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the October issue of Eliot's magazine The Criterion and in the United States in the November issue of The Dial. Among its famous phrases are "April is the cruellest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust", and "These fragments I have shored against my ruins".

Jean Jules Verdenal was a French medical officer who served, and was killed, during the First World War. Verdenal and his life remain obscure; the little that is known comes mainly from interviews with family members and several surviving letters.

East Coker is the second poem of T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets. It was started as a way for Eliot to get back into writing poetry and was modelled after Burnt Norton. It was finished during early 1940 and printed in the UK in the Easter edition of the 1940 New English Weekly, and in the US in the May 1940 issue of Partisan Review. The title refers to a village in Somerset that was connected to his Eliot family ancestry and where Eliot's ashes were placed in St Michael and All Angels' Church, East Coker.

Burnt Norton is the first poem of T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets. He created it while working on his play Murder in the Cathedral, and it was first published in his Collected Poems 1909–1935 (1936). The poem's title refers to the manor house Eliot visited with Emily Hale in the Cotswolds. The manor's garden serves as an important image within the poem. Structurally, the poem is based on Eliot's The Waste Land, with passages of the poem related to those excised from Murder in the Cathedral.

Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot was the first wife of American-British poet T. S. Eliot, whom she married in 1915, less than three months after their introduction by mutual friends, when Vivienne was a governess in Cambridge and Eliot was studying at Oxford.

Keith Alldritt is a contemporary British novelist, biographer and critic.

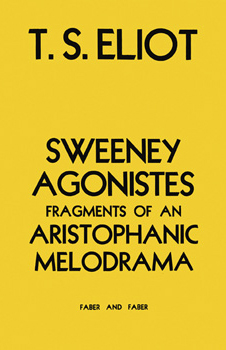

Sweeney Agonistes by T. S. Eliot was his first attempt at writing a verse drama although he was unable to complete the piece. In 1926 and 1927 he separately published two scenes from this attempt and then collected them in 1932 in a small book under the title Sweeney Agonistes: Fragments of an Aristophanic Melodrama. The scenes are frequently performed together as a one-act play. Sweeney Agonistes is currently available in print in Eliot's Collected Poems: 1909–1962 listed under his "Unfinished Poems" with the "Fragments of an Aristophanic Melodrama" part of the play's original title removed. The scenes are separately titled "Fragment of a Prologue" and "Fragment of an Agon".

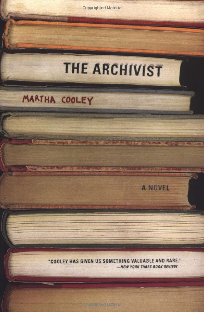

The Archivist is an American novel by Martha Cooley, first published in a hardcover format by Little, Brown and Company in 1998. The story makes extensive reference to the poetry of T. S. Eliot, and it dwells on themes such as guilt, insanity, and suicide. The book was reprinted in 1999 by Back Bay Books, an imprint of Little, Brown and Company.