Energy rationing primarily involves measures that are designed to force energy conservation as an alternative to price mechanisms in energy markets. Because of its economic consequences energy rationing is used as method of last resort, often at times of emergency such as during an energy crisis.

Examples of energy rationing include fuel rationing and the use of ration books or ration stamps to restrict personal consumption. Energy rationing may include penalties such as surcharges and disconnection from electrical supply for those who choose not to reduce their demand voluntarily.

Load shedding is a common form of energy rationing used when electricity markets cannot keep up to demand, particularly peak demand. Limited electrical supply from power stations at times of drought or after infrastructure is damaged, can lead authorities to implement rationing. Brazil was forced to implement energy rationing due to drought in 2001. [1] Reducing demand in this way aims to avoid forced power outages which are more disruptive than rationing. [1]

Tradable Energy Quotas is an energy rationing system designed to enable nations to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases along with their use of oil, gas and coal, and to ensure fair access to energy for all.

One issue with energy rationing is the cost of setting up rationing schemes. Another criticism is that energy rationing schemes are unworkable and face many practical problems including consumer lawsuits. [1] Due to the general disdain for restrictions that interfere with existing personal freedoms, such as ecotaxes and carbon rationing, energy rationing is not favoured by policy makers to mitigate global warming. [2]

As oil becomes more scarce due to oil depletion countries that have reserve currencies will prefer to buy oil rather than ration it. [3] The Oil Depletion Protocol is form of energy rationing that was developed by Richard Heinberg to ensure that price rationing does not price out poorer countries. [4]

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time. There are many forms of rationing, although rationing by price is most prevalent.

An energy crisis or energy shortage is any significant bottleneck in the supply of energy resources to an economy. In literature, it often refers to one of the energy sources used at a certain time and place, in particular, those that supply national electricity grids or those used as fuel in industrial development and population growth have led to a surge in the global demand for energy in recent years. In the 2000s, this new demand – together with Middle East tension, the falling value of the US dollar, dwindling oil reserves, concerns over peak oil, and oil price speculation – triggered the 2000s energy crisis, which saw the price of oil reach an all-time high of $147.30 per barrel ($926/m3) in 2008.

Peak oil is the moment at which extraction of petroleum reaches a rate greater than that at any time in the past and starts to permanently decrease. It is related to the distinct concept of oil depletion; while global petroleum reserves are finite, the limiting factor is not whether the oil exists but whether it can be extracted economically at a given price. A secular decline in oil extraction could be caused both by depletion of accessible reserves and by reductions in demand that reduce the price relative to the cost of extraction, as might be induced to reduce carbon emissions.

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of goods even during shortages, and to slow inflation, or, alternatively, to ensure a minimum income for providers of certain goods or to try to achieve a living wage. There are two primary forms of price control: a price ceiling, the maximum price that can be charged; and a price floor, the minimum price that can be charged. A well-known example of a price ceiling is rent control, which limits the increases that a landlord is permitted by government to charge for rent. A widely used price floor is minimum wage. Historically, price controls have often been imposed as part of a larger incomes policy package also employing wage controls and other regulatory elements.

From the mid-1980s to September 2003, the inflation-adjusted price of a barrel of crude oil on NYMEX was generally under US$25/barrel in 2008 dollars. During 2003, the price rose above $30, reached $60 by 11 August 2005, and peaked at $147.30 in July 2008. Commentators attributed these price increases to many factors, including Middle East tension, soaring demand from China, the falling value of the U.S. dollar, reports showing a decline in petroleum reserves, worries over peak oil, and financial speculation.

Energy demand management, also known as demand-side management (DSM) or demand-side response (DSR), is the modification of consumer demand for energy through various methods such as financial incentives and behavioral change through education.

Demand response is a change in the power consumption of an electric utility customer to better match the demand for power with the supply. Until recently electric energy could not be easily stored, so utilities have traditionally matched demand and supply by throttling the production rate of their power plants, taking generating units on or off line, or importing power from other utilities. There are limits to what can be achieved on the supply side, because some generating units can take a long time to come up to full power, some units may be very expensive to operate, and demand can at times be greater than the capacity of all the available power plants put together. Demand response seeks to adjust the demand for power instead of adjusting the supply.

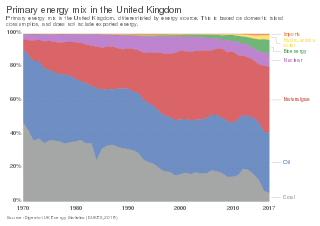

Total energy consumption in the United Kingdom was 142.0 million tonnes of oil equivalent in 2019. In 2014, the UK had an energy consumption per capita of 2.78 tonnes of oil equivalent compared to a world average of 1.92 tonnes of oil equivalent. Demand for electricity in 2014 was 34.42 GW on average coming from a total electricity generation of 335.0 TWh.

The energy policy of the United Kingdom has achieved success in reducing energy intensity, reducing energy poverty, and maintaining energy supply reliability to date. The United Kingdom has an ambitious goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions for future years, but it is unclear whether the programs in place are sufficient to achieve this objective. Regarding energy self sufficiency, the United Kingdom policy does not address this issue, other than to concede historic energy self sufficiency is currently ceasing to exist. With regard to transport, the United Kingdom historically has a good policy record encouraging public transport links with cities, despite encountering problems with high speed trains, which have the potential to reduce dramatically domestic and short-haul European flights. The policy does not, however, significantly encourage hybrid vehicle use or ethanol fuel use, options which represent viable short term means to moderate rising transport fuel consumption. Regarding renewable energy, the United Kingdom has goals for wind and tidal energy. The White Paper on Energy, 2007, set the target that 20% of the UK's energy must come from renewable sources by 2020.

The energy policy of Australia is subject to the regulatory and fiscal influence of all three levels of government in Australia, although only the State and Federal levels determine policy for primary industries such as coal. Federal policies for energy in Australia continue to support the coal mining and natural gas industries through subsidies for fossil fuel use and production. Australia is the 10th most coal-dependent country in the world. Coal and natural gas, along with oil-based products, are currently the primary sources of Australian energy usage and the coal industry produces over 30% of Australia's total greenhouse gas emissions. In 2018 Australia was the 8th highest emitter of greenhouse gases per capita in the world.

Natural gas is a commodity that can be stored for an indefinite period of time in natural gas storage facilities for later consumption.

Peak demand on an electrical grid is simply the highest electrical power demand that has occurred over a specified time period. Peak demand is typically characterized as annual, daily or seasonal and has the unit of power. Peak demand, peak load or on-peak are terms used in energy demand management describing a period in which electrical power is expected to be provided for a sustained period at a significantly higher than average supply level. Peak demand fluctuations may occur on daily, monthly, seasonal and yearly cycles. For an electric utility company, the actual point of peak demand is a single half-hour or hourly period which represents the highest point of customer consumption of electricity. At this time there is a combination of office, domestic demand and at some times of the year, the fall of darkness.

The mitigation of peak oil is the attempt to delay the date and minimize the social and economic effects of peak oil by reducing the consumption of and reliance on petroleum. By reducing petroleum consumption, mitigation efforts seek to favorably change the shape of the Hubbert curve, which is the graph of real oil production over time predicted by Hubbert peak theory. The peak of this curve is known as peak oil, and by changing the shape of the curve, the timing of the peak in oil production is affected. An analysis by the author of the Hirsch report showed that while the shape of the oil production curve can be affected by mitigation efforts, mitigation efforts are also affected by the shape of Hubbert curve.

The electricity sector in Brazil is the largest in Latin America. Its capacity at the end of 2021 was 181,532 MW. The installed capacity grew from 11,000 MW in 1970 with an average yearly growth of 5.8% per year. Brazil has the largest capacity for water storage in the world, being dependent on hydroelectricity generation capacity, which meets over 60% of its electricity demand. The national grid runs at 60 Hz and is powered 83% from renewable sources. This dependence on hydropower makes Brazil vulnerable to power supply shortages in drought years, as was demonstrated by the 2001–2002 energy crisis.

The energy policy of Malaysia is determined by the Malaysian Government, which address issues of energy production, distribution, and consumption. The Department of Electricity and Gas Supply acts as the regulator while other players in the energy sector include energy supply and service companies, research and development institutions and consumers. Government-linked companies Petronas and Tenaga Nasional Berhad are major players in Malaysia's energy sector.

The electricity sector of Uruguay has traditionally been based on domestic hydropower along with thermal power plants, and reliant on imports from Argentina and Brazil at times of peak demand. Over the last 10 years, investments in renewable energy sources such as wind power and solar power allowed the country to cover in early 2016 94.5% of its electricity needs with renewable energy sources.

Energy consumption per person in Turkey is similar to the world average, and over 85 percent is from fossil fuels. From 1990 to 2017 annual primary energy supply tripled, but then remained constant to 2019. In 2019, Turkey's primary energy supply included around 30 percent oil, 30 percent coal, and 25 percent gas. These fossil fuels contribute to Turkey's air pollution and its above average greenhouse gas emissions. Turkey mines its own lignite but imports three-quarters of its energy, including half the coal and almost all the oil and gas it requires, and its energy policy prioritises reducing imports. The OECD has criticised the lack of carbon pricing, fossil fuel subsidies and the country's under-utilized wind and solar potential. The country's electricity is generated mainly from coal, gas and hydroelectricity; with a small but growing amount from wind, solar and geothermal. However, Black Sea gas is forecast to meet all residential demand from the late 2020s. A nuclear power plant is also under construction, and one half of installed power capacity is renewable energy. Despite this, from 1990 to 2019, carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion rose from 130 megatonnes (Mt) to 360 Mt.

The United Kingdom is committed to legally binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets of 34% by 2020 and 80% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels, as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008. Decarbonisation of electricity generation will form a major part of this reduction and is essential before other sectors of the economy can be successfully decarbonised.

Venezuela has experienced a marked deficit in the generation of electrical energy. The immediate cause of the energy crisis was a prolonged drought that caused the water in the reservoir of the Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Plant to reach very low levels. Although various measures were taken to overcome the crisis, one of the most controversial was the implementation of a program of electrical rationing throughout the country, except in the capital Caracas, which was ultimately officially suspended in June 2010, due to the recovery of reservoirs due to the rains, and not to interrupt the transmission of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Power cuts have continued to occur in the interior of the country, although with less frequency and duration, this time driven by failures in other parts of the system. The situation of "electrical emergency" decreed by the government on 21 December 2009 was suspended on 30 November 2010; however, on 14 May 2011, after the country experienced two national blackouts, the government of Hugo Chávez announced a temporary rationing plan and acknowledged that the electricity system continued to face "generation weaknesses" that they did not expect to surpass until end the year.

The 2021–2022 global energy crisis is the most recent in a series of cyclical energy shortages experienced over the last fifty years. It is more acutely affecting countries such as the United Kingdom and China, among others.