Kami are the deities, divinities, spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the Shinto religion. They can be elements of the landscape, forces of nature, beings and the qualities that these beings express, and/or the spirits of venerated dead people. Many kami are considered the ancient ancestors of entire clans. Traditionally, great leaders like the Emperor could be or became kami.

Shinto is a religion originating from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners Shintoists, although adherents rarely use that term themselves. There is no central authority in control of Shinto, with much diversity of belief and practice evident among practitioners.

Benzaiten, is an East Asian Buddhist goddess who originated mainly from the Hindu Indian Saraswati, goddess of speech, the arts, and learning. Worship of Benzaiten arrived in Japan during the sixth through eighth centuries, mainly via Classical Chinese translations of the Golden Light Sutra, which has a section devoted to her. Benzaiten was also adopted into Shinto religion, and there are several Shinto shrines dedicated to her.

Izumo-taisha, officially Izumo Ōyashiro, is one of the most ancient and important Shinto shrines in Japan. No record gives the date of establishment. Located in Izumo, Shimane Prefecture, it is home to two major festivals. It is dedicated to the god Ōkuninushi, famous as the Shinto deity of marriage and to Kotoamatsukami, distinguishing heavenly kami. The shrine is believed by many to be the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan, even predating the Ise Grand Shrine.

A Shinto shrine is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more kami, the deities of the Shinto religion.

Yasaka Shrine, once called Gion Shrine, is a Shinto shrine in the Gion District of Kyoto, Japan. Situated at the east end of Shijō-dōri, the shrine includes several buildings, including gates, a main hall and a stage. The Yasaka shrine is dedicated to Susanoo in the tradition of the Gion faith as its chief kami, with his consort Kushinadahime on the east, and eight offspring deities on the west. The yahashira no mikogami include Yashimajinumi no kami, Itakeru no kami, Ōyatsuhime no kami, Tsumatsuhime no kami, Ōtoshi no kami, Ukanomitama no kami, Ōyatsuhiko no kami, and Suseribime no mikoto.

Shinbutsu-shūgō, also called Shinbutsu shūShinbutsu-konkō, is the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism that was Japan's main organized religion up until the Meiji period. Beginning in 1868, the new Meiji government approved a series of laws that separated Japanese native kami worship, on one side, from Buddhism which had assimilated it, on the other.

Shinatsuhiko is a Japanese mythological god of wind (Fūjin). Another name for this deity is Shinatobe, who originally may have been a separate goddess of wind.

Kagutsuchi, also known as Hi-no-Kagutsuchi or Homusubi among other names, is the kami of fire in classical Japanese mythology.

Sumiyoshi-taisha (住吉大社), also known as Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine, is a Shinto shrine in Sumiyoshi-ku, Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, Japan. It is the main shrine of all the Sumiyoshi shrines in Japan. However, the oldest shrine that enshrines the Sumiyoshi sanjin, the three Sumiyoshi kami, is the Sumiyoshi Shrine in Hakata.

The Japanese word mitama refers to the spirit of a kami or the soul of a dead person. It is composed of two characters, the first of which, mi, is simply an honorific. The second, tama (魂・霊) means "spirit". The character pair 神霊, also read mitama, is used exclusively to refer to a kami's spirit. Significantly, the term mitamashiro is a synonym of shintai, the object which in a Shinto shrine houses the enshrined kami.

Toyouke-hime is the goddess of agriculture, industry, food, clothing, and houses in the Shinto religion. Originally enshrined in the Tanba region of Japan, she was called to reside at Gekū, Ise Shrine, about 1,500 years ago at the age of Emperor Yūryaku to offer sacred food to Amaterasu Ōmikami, the Sun Goddess.

Watatsumi, also pronounced Wadatsumi, is a legendary kami, Japanese dragon and tutelary water deity in Japanese mythology. Ōwatatsumi no kami is believed to be another name for the sea deity Ryūjin and also for the Watatsumi Sanjin, which rule the upper, middle and lower seas respectively and were created when Izanagi was washing himself of the dragons blood when he returned from Yomi, "the underworld".

The following is a family tree of the emperors of Japan, from the legendary Emperor Jimmu to the present monarch, Naruhito.

Kushinadahime (櫛名田比売、くしなだひめ), also known as Kushiinadahime (奇稲田姫、くしいなだひめ) or Inadahime (稲田姫、いなだひめ) among other names, is a goddess (kami) in Japanese mythology and the Shinto faith. According to these traditions, she is one of the wives of the god Susanoo, who rescued her from the monster Yamata no Orochi. As Susanoo's wife, she is a central deity of the Gion cult and worshipped at Yasaka Shrine.

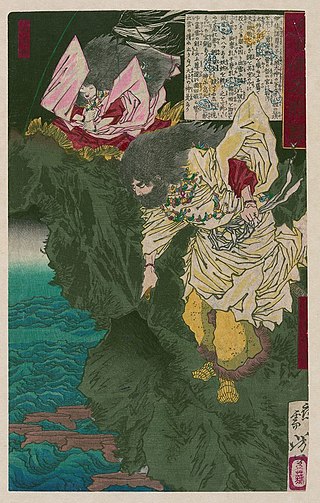

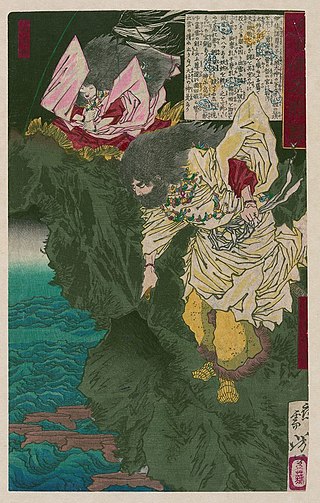

Atago Gongen (愛宕権現) also known as Tarōbō (太郎坊) of Mount Atago is a Japanese kami and tengu believed to be the local avatar (Gongen) of Buddhist bodhisattva Jizō and Shinto goddess Izanami. He is mounted on a white horse and carries a ringed staff and desire-cancelling jewel. The cult originated in Shugendō practices on Mount Atago in Kyoto, and Atago Gongen is worshiped as a protector against fire and a god of war by Samurai. There are some nine hundred Atago Shrines around Japan.

In Japan, a chinjusha is a Shinto shrine which enshrines a tutelary kami; that is, a patron spirit that protects a given area, village, building or a Buddhist temple. The Imperial Palace has its own tutelary shrine dedicated to the 21 guardian gods of Ise Shrine. Tutelary shrines are usually very small, but there is a range in size, and the great Hiyoshi Taisha for example is Enryaku-ji's tutelary shrine. The tutelary shrine of a temple or the complex the two together form are sometimes called a temple-shrine. If a tutelary shrine is called chinju-dō, it is the tutelary shrine of a Buddhist temple. Even in that case, however, the shrine retains its distinctive architecture.

Until the Meiji period (1868–1912), the jingū-ji were places of worship composed of a Buddhist temple and a Shintō shrine, both dedicated to a local kami. These complexes were born when a temple was erected next to a shrine to help its kami with its karmic problems. At the time, kami were thought to be also subjected to karma, and therefore in need of a salvation only Buddhism could provide. Having first appeared during the Nara period (710–794), jingū-ji remained common for over a millennium until, with few exceptions, they were destroyed in compliance with the Kami and Buddhas Separation Act of 1868. Seiganto-ji is a Tendai temple part of the Kumano Sanzan Shinto shrine complex, and as such can be considered one of the few shrine-temples still extant.

Izawa-no-miya (伊雑宮) is a Shinto shrine in the Kaminogō neighborhood of Isobe in the city of Shima in Mie Prefecture, Japan. It is one of the two shrines claiming the title of ichinomiya of former Shima Province. Together with the Takihara-no-miya (瀧原宮) in Taiki, it is one of the Amaterasu-Ōkami no Tonomiya (天照大神の遙宮), or external branches of the Inner Shrine of the Ise Grand Shrine.

Izawa Jinja (伊射波神社) is a Shinto shrine in the Arashima neighborhood of the city of Toba in Mie Prefecture, Japan. It is one of the two shrines claiming the title of ichinomiya of former Shima Province. The main festivals of the shrine are held annually on January 9, June 7 and November 23. It is also referred to as the Shima Daimyōjin (志摩大明神).