The Pleistocene is the geological epoch that lasted from c. 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in 2009 by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the cutoff of the Pleistocene and the preceding Pliocene was regarded as being 1.806 million years Before Present (BP). Publications from earlier years may use either definition of the period. The end of the Pleistocene corresponds with the end of the last glacial period and also with the end of the Paleolithic age used in archaeology. The name is a combination of Ancient Greek πλεῖστος (pleîstos) 'most' and καινός 'new'.

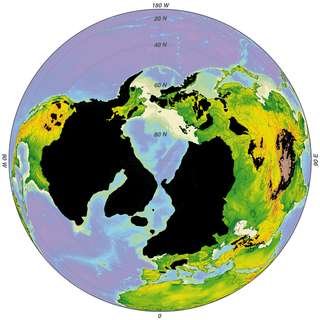

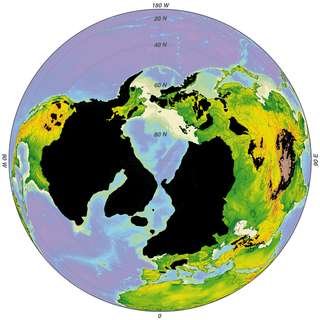

The Wisconsin glaciation, also called the Wisconsin glacial episode, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex, peaking more than 20,000 years ago. This advance included the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which nucleated in the northern North American Cordillera; the Innuitian ice sheet, which extended across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago; the Greenland ice sheet; and the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered the high latitudes of central and eastern North America. This advance was synchronous with global glaciation during the last glacial period, including the North American alpine glacier advance, known as the Pinedale glaciation. The Wisconsin glaciation extended from about 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, between the Sangamonian Stage and the current interglacial, the Holocene. The maximum ice extent occurred about 25,000–21,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum, also known as the Late Wisconsin in North America.

The Last Glacial Period (LGP), also known as the Last glacial cycle, occurred from the end of the Last Interglacial to the beginning of the Holocene, c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 years ago, and thus corresponds to most of the timespan of the Late Pleistocene.

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

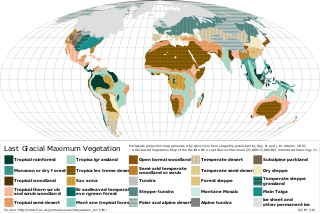

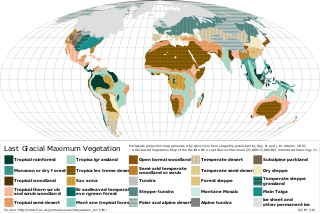

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago. Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Europe, and Asia and profoundly affected Earth's climate by causing a major expansion of deserts, along with a large drop in sea levels.

The Cordilleran ice sheet was a major ice sheet that periodically covered large parts of North America during glacial periods over the last ~2.6 million years.

In biology, a refugium is a location which supports an isolated or relict population of a once more widespread species. This isolation (allopatry) can be due to climatic changes, geography, or human activities such as deforestation and overhunting.

The mammoth steppe, also known as steppe-tundra, was once the Earth's most extensive biome. During glacial periods in the later Pleistocene it stretched east-to-west, from the Iberian Peninsula in the west of Europe, then across Eurasia and through Beringia and into the Yukon in northwest Canada; from north-to-south, the steppe reached from the Arctic southward to southern Europe, Central Asia and northern China. The mammoth steppe was cold and dry, and relatively featureless, though climate, topography, and geography varied considerably throughout. Certain areas of the biome—such as coastal areas—had wetter and milder climates than others. Some areas featured rivers which, through erosion, naturally created gorges, gulleys, or small glens. The continual glacial recession and advancement over millennia contributed more to the formation of larger valleys and different geographical features. Overall, however, the steppe is known to be flat and expansive grassland. The vegetation was dominated by palatable, high-productivity grasses, herbs and willow shrubs.

The Oldest Dryas is a biostratigraphic subdivision layer corresponding to a relatively abrupt climatic cooling event, or stadial, which occurred during the last glacial retreat. The time period to which the layer corresponds is poorly defined and varies between regions, but it is generally dated as starting at 18.5–17 thousand years (ka) before present (BP) and ending 15–14 ka BP. As with the Younger and Older Dryas events, the stratigraphic layer is marked by abundance of the pollen and other remains of Dryas octopetala, an indicator species that colonizes arctic-alpine regions. The termination of the Oldest Dryas is marked by an abrupt oxygen isotope excursion, which has been observed at many sites in the Alps that correspond to this interval of time.

Last Glacial Maximum refugia were places (refugia) in which humans and other species survived during the Last Glacial Period, around 25,000 to 18,000 years ago. Glacial refugia are areas that climate changes were not as severe, and where species could recolonize after deglaciation.

The British-Irish Ice Sheet (BIIS), a component of which was the Irish Sea Glacier was an ice sheet during the Pleistocene Ice Age that, probably on more than one occasion, flowed southwards from its source areas in Scotland and Ireland and across the Isle of Man, Anglesey and Pembrokeshire. It probably reached its maximum extent during the Anglian Glaciation, and it was also extensive during the Late Devensian Glaciation.

The Weichselian glaciation is the regional name for the Last Glacial Period in the northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet that spread out from the Scandinavian Mountains and extended as far as the east coast of Schleswig-Holstein, northern Poland and Northwest Russia. This glaciation is also known as the Weichselian ice age, Vistulian glaciation, Weichsel or, less commonly, the Weichsel glaciation, Weichselian cold period (Weichsel-Kaltzeit), Weichselian glacial (Weichsel-Glazial), Weichselian Stage or, rarely, the Weichselian complex (Weichsel-Komplex).

The island of Borneo is located on the Sunda Shelf, which is an extensive region in Southeast Asia of immense importance in terms of biodiversity, biogeography and phylogeography of fauna and flora that had attracted Alfred Russel Wallace and other biologists from all over the world.

The ABC Islands bear or Sitka brown bear is a subspecies or population of brown bear that resides in Southeast Alaska and is found on Admiralty Island, Baranof Island, and Chichagof Island in Alaska, and a part of the Alexander Archipelago. It has a unique genetic structure that relates them not only to brown bears, but also to polar bears. Its habitat exists within the Tongass National Forest, which is part of the perhumid rainforest zone.

A glacial refugium is a geographic region which made possible the survival of flora and fauna during ice ages and allowed for post-glacial re-colonization. Different types of glacial refugia can be distinguished, namely nunatak, peripheral, and lowland. Glacial refugia have been suggested as a major cause of floral and faunal distribution patterns in both temperate and tropical latitudes. With respect to disjunct populations of modern-day species, especially in birds, doubt has been cast on the validity of such inferences, as much of the differentiation between populations observed today may have occurred before or after their restriction to refugia. In contrast, isolated geographic locales that host one or more critically endangered species are generally uncontested as bona fide glacial refugia.

The Vashon Glaciation, Vashon Stadial or Vashon Stade is a local term for the most recent period of very cold climate in which during its peak, glaciers covered the entire Salish Sea as well as present day Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia and other surrounding areas in the western part of present-day Washington (state) of the United States of America. This occurred during a cold period around the world known as the last glacial period. This was the most recent cold period of the Quaternary glaciation, the time period in which the arctic ice sheets have existed. The Quaternary Glaciation is part of the Late Cenozoic Ice Age, which began 33.9 million years ago and is ongoing. It is the time period in which the Antarctic ice cap has existed.

The last glacial period and its associated glaciation is known in southern Chile as the Llanquihue glaciation. Its type area lies west of Llanquihue Lake where various drifts or end moraine systems belonging to the last glacial period have been identified. The glaciation is the last episode of existence of the Patagonian Ice Sheet. Around Nahuel Huapi Lake the equivalent glaciation is known as the Nahuel Huapi Drift.

According to the northern cryptic glacial refugial hypothesis, during the last ice age cold tolerant plant and animal species persisted in ice-free microrefugia north of the Alps in Europe. The alternative hypothesis of no persistence and postglacial immigration of plants and animals from southern refugia in Europe is sometimes also called the tabula rasa hypothesis.

The peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum. These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago. The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by proposed linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.

The coastal migration hypothesis is one of two leading hypothesis about the settlement of the Americas at the time of the Last Glacial Maximum. It proposes one or more migration routes involving watercraft, via the Kurile island chain, along the coast of Beringia and the archipelagos off the Alaskan-British Columbian coast, continuing down the coast to Central and South America. The alternative is the hypothesis solely by interior routes, which assumes migration along an ice-free corridor between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets during the Last Glacial Maximum.