Dharma is a key concept with multiple meanings in the Indian religions, among others. Although no single-word translation exists for dharma in English, the term is commonly understood as referring to behaviours that are in harmony with the "order and custom" that sustain life; "virtue", or "religious and moral duties".

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a comprehensive resource to scholars and academic researchers, as well as describing usage in its many variations throughout the world.

Harold James Ruthven Murray was a British educationalist, inspector of schools, and prominent chess historian. His book, A History of Chess, is widely regarded as the most authoritative and comprehensive history of the game.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Hinduism:

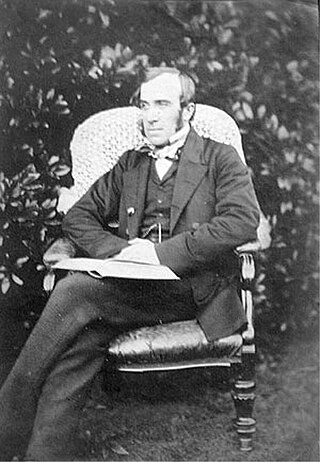

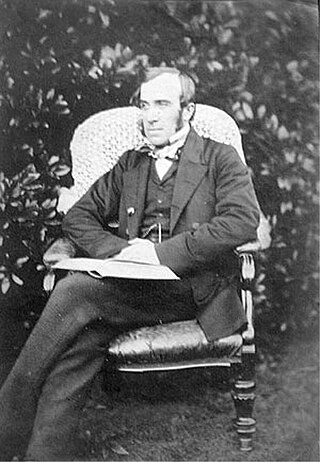

Frederick James Furnivall was an English philologist, best known as one of the co-creators of the New English Dictionary. He founded a number of learned societies on early English literature and made pioneering and massive editorial contributions to the subject, of which the most notable was his parallel text edition of The Canterbury Tales. He was one of the founders of and teachers at the London Working Men's College and a lifelong campaigner against injustice.

Henry Bradley, FBA was a British philologist and lexicographer who succeeded James Murray as senior editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Pashupati is a Hindu deity and an incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva as the "Lord of the animals". Pashupati is mainly worshipped in Nepal and India. Pashupati is also the national deity of Nepal.

Friedrich Max Müller was a British philologist and Orientalist of German origin. He was one of the founders of the Western academic disciplines of Indian studies and religious studies. Müller wrote both scholarly and popular works on the subject of Indology. The Sacred Books of the East, a 50-volume set of English translations, was prepared under his direction. He also promoted the idea of a Turanian family of languages.

Sir Monier Monier-Williams was a British scholar who was the second Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University, England. He studied, documented and taught Asian languages, especially Sanskrit, Persian and Hindustani.

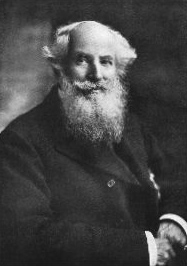

Sir James Augustus Henry Murray, FBA was a British lexicographer and philologist. He was the primary editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) from 1879 until his death.

Charles Rockwell Lanman was an American scholar of the Sanskrit language.

Alain Daniélou was a French historian, Indologist, intellectual, musicologist, translator, writer, and notable Western convert to and expert on the Shaivite branch of Hinduism.

Simon Theodor Aufrecht was a German Indologist and comparative linguist. He was the first Professor of Sanskrit and Comparative Philology at the University of Edinburgh, and subsequently spent two decades as Professor of Indology at the University of Bonn.

Professor Johann Georg Bühler was a German scholar of ancient Indian languages and law.

Sanskrit has been studied by Western scholars since the late 18th century. In the 19th century, Sanskrit studies played a crucial role in the development of the field of comparative linguistics of the Indo-European languages. During the British Raj (1857–1947), Western scholars edited many Sanskrit texts which had survived in manuscript form. The study of Sanskrit grammar and philology remains important both in the field of Indology and of Indo-European studies.

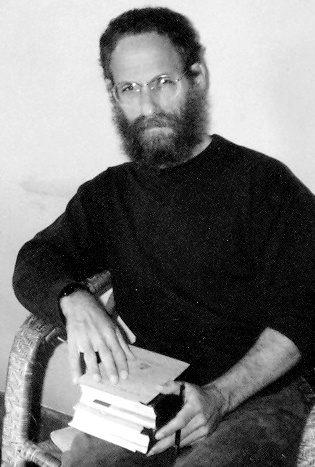

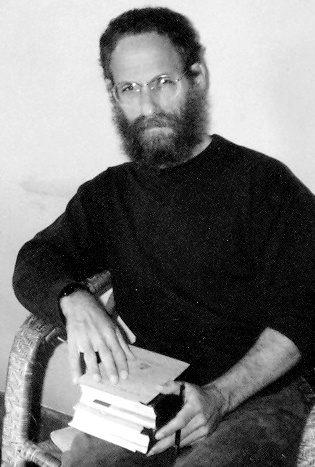

Sheldon I. Pollock is an American scholar of Sanskrit, the intellectual and literary history of India, and comparative intellectual history. He is the Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies at Columbia University. He was the general editor of the Clay Sanskrit Library and the founding editor of the Murty Classical Library of India.

TarkateerthaLakshman Shastri Joshi was an Indian scholar, of Sanskrit, Hindu Dharma, and a Marathi literary critic, and supporter of Indian independence. Mahatma Gandhi chose him to be his principal advisor in his campaign against untouchability. Joshi was the first recipient of Sahitya Akademi Award in year 1955. He was also awarded with two of the India's highest civilian honours Padma Bhushan in 1973 and Padma Vibhushan in 1992

Matthew Atmore Sherring (1826–1880), usually cited as M. A. Sherring, was a Anglican missionary in British India who was also an Indologist and wrote a number of works related to India. He was educated at Coward College, a dissenting academy in London that trained people for nonconformist ministry.

Ātma-bodha is a short Sanskrit text attributed to Adi Shankara of Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy. The text in sixty-eight verses describes the path to Self-knowledge or the awareness of Atman.

The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary is a 2006 book by three editors of the Oxford English Dictionary, Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner. It examines J. R. R. Tolkien's brief period working as a lexicographer with the OED after World War I, traces his use of philology as it is apparent in his writings, and in particular in his legendarium, and finally examines in detail over 100 words that he used, developed or invented.