The Constitution provides for the freedom to practice the rights of one's religion and faith in accordance with the customs that are observed in the kingdom, unless they violate public order or morality. The state religion is Islam. The Government prohibits conversion from Islam and proselytization of Muslims.

In June 2006, the Government published the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in the Official Gazette, which, according to Article 93.2 of the Constitution, gives the Covenant the force of law. Article 18 of the ICCPR provides for freedom of religion (See Legal and policy framework). Despite this positive development, restrictions and some abuses continued. Members of unrecognized religious groups and converts from Islam face legal discrimination and bureaucratic difficulties as well as societal intolerance; Shari'a courts have the authority to prosecute proselytizers. [1]

In 2022 Muslims made up about 97.2% of the country's population; [1] there were almost 750,000 refugees and other displaced persons registered in the country, mainly Sunni Muslims from Syria.

In the same year, Christians made up 2.1% of the country's population. [1] A 2015 study estimated 6,500 Christian believers, from a Muslim background, were in the country (mainly Protestant). [2] It was also noted that the country has a small number of Buddhists, Hindus, Zoroastrians and Yezidis. [1]

In 2022, officially recognized Christian denominations include the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic (Melkite), Armenian Orthodox, Maronite Catholic, Coptic, Anglican, Lutheran, Seventh-day Adventist, United Pentecostal and Syrian Orthodox churches. Other Christian groups with some recognition include the Free Evangelicals, the Church of the Nazarene, the Assembly of God, the Baptist Church and the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

In 2020, there were approximately 14,000 Druze in the country, and 1,000 people following the Baháʼí Faith; [3] there were reported to be no Jewish citizens.

There are a number of Syriac Christians (who are overwhelmingly ethnic Assyrians) and Shi'a among the estimated 250,000 to 450,000 Iraqis in the country, many of whom are undocumented or on visitor permits.

With few exceptions, there are no major geographic concentrations of religious minorities. The cities of Husn, in the north, and Fuheis, near Amman, are predominantly Christian. Madaba and Karak, both south of Amman, also have significant Christian populations. The northern part of the city of Azraq has a sizable Druze population, as does Umm Al-Jamal in the governorate of Mafraq. There also are Druze populations in Amman and Zarka and a smaller number in Irbid and Aqaba. There are a number of nonindigenous Shi'a living in the Jordan Valley and the south. The Druze are registered as "Muslims" and, as they have their own court in Al-Azraq, can administer their own personal status matters.

In 2023, the country was scored 2 out of 4 for religious freedom. [4]

According to US Department of State's Human Rights Reports in 2015 legal and societal discrimination and harassment remained a problem for religious minorities, and religious converts. [5]

The Constitution provides for the freedom to practice the rites of one's religion and faith in accordance with the customs that are observed in the kingdom, unless they violate public order or morality. According to the Constitution the state religion is Islam and the King must be Muslim. The Government prohibits conversion from Islam and proselytization of Muslims.

The Constitution, in Articles 103-106, provides that matters concerning the personal status of Muslims are the exclusive jurisdiction of Shari'a courts which apply Shari'a law in their proceedings. Personal status includes religion, marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance. Personal status law follows the guidelines of the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence, which is applied to cases that are not explicitly addressed by civil status legislation. Matters of personal status of non-Muslims whose religion is recognized by the Government are the jurisdiction of Tribunals of Religious Communities, according to Article 108.

There is no provision for civil marriage or divorce. Some Christians are unable to divorce under the legal system because they are subject to their denomination's religious court system, which does not allow divorce. Such individuals sometimes convert to another Christian denomination or to Islam to divorce legally.

The head of the department that manages Shari'a court affairs (a cabinet-level position) appoints Shari'a judges, while each recognized non-Muslim religious community selects the structure and members of its own tribunal. All judicial nominations are approved by the Prime Minister and commissioned officially by royal decree. The Protestant denominations registered as "societies" come under the jurisdiction of one of the recognized Protestant church tribunals. There are no tribunals assigned for atheists or adherents of unrecognized religions such as the Baháʼí Faith. Such individuals must request one of the recognized courts to hear their personal status cases.

Shari'a is applied in all matters relating to family law involving Muslims or the children of a Muslim father, and all citizens, including non-Muslims, are subject to Islamic legal provisions regarding inheritance. According to the law, all minor children of male citizens who convert to Islam are considered to be Muslim. Adult children of a male Christian who has converted to Islam become ineligible to inherit from their father if they do not also convert to Islam. In cases in which a Muslim converts to Christianity, the authorities do not recognize the conversion as legal, and the individual continues to be treated as a Muslim in matters of family and property law.

While Christianity is a recognized religion and non-Muslim citizens may profess and practice the Christian faith, churches must be accorded legal recognition through administrative procedures in order to own land and administer sacraments, including marriage. Churches and other religious institutions can receive official recognition by applying to the Prime Ministry. The Prime Minister unofficially confers with an interfaith council of clergy representing officially registered local churches on all matters relating to the Christian community, including the registration of new churches. The Government refers to the following criteria when considering official recognition of Christian churches: the faith must not contradict the nature of the Constitution, public ethics, customs, or traditions; it must be recognized by the Middle East Council of Churches; the faith must not oppose the national religion; and the group must include some citizen adherents. Groups that the Government deems to engage in practices that violate the law and the nature of society or threaten the stability of public order are prohibited; however, there were no reports of banned religious groups. The Government does not interfere with public worship by the country's Christian minority.

Recognized non-Muslim religious institutions do not receive subsidies; they are financially and administratively independent of the Government and are tax-exempt. The Free Evangelicals, the Church of the Nazarene, the Assembly of God, and the Christian and Missionary Alliance, are registered with the Ministry of Interior as "societies" but not as churches

Public schools provide mandatory religious instruction for all Muslim students. Christian students are not required to attend courses that teach Islam. The Constitution provides that congregations have the right to establish schools for the education of their own communities "provided that they comply with the general provisions of the law and are subject to government control in matters relating to their curriculums and orientation."

In June 2006, the Government published the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in the Official Gazette. According to Article 93.2 of the Constitution, acts published in the Official Gazette attain force of law. Article 18 of the Covenant states that everyone shall have the "right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion," including freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom "to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice, and teaching." Additionally, the Covenant stipulates that no one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice. The country ratified the ICCPR without reservations in 1976. However, Article 2, Section 2 of the ICCPR states that the Covenant is not self-executing, and requires implementing legislation to give the Covenant effect. By the end of the reporting period, no such legislation had been proposed. Nevertheless, a senior official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the ICCPR's publication in the Official Gazette signifies that the Government considers the Covenant as a source of law alongside domestic law, including the Constitution and Shari'a (Islamic law). Articles 103-106 of the Constitution still provide that matters concerning the personal status of Muslims, including religion, are the exclusive jurisdiction of Shari'a courts which apply Shari'a (Hanafi) in their proceedings.

The government-sponsored Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies organized several conferences and seminars to support its effort to provide a venue in the Arab world for the interdisciplinary study and rational discussion of religion and religious issues, with particular reference to Christianity in Arab and Islamic society. These included an international conference in January 2007 to debate a common approach to reform in different religious traditions, a February 2007 seminar that addressed the role of religious traditions in the context of social and political modernization, and an April 2007 conference entitled "The ‘Universal' in Human Rights: A Precondition for a Dialogue of Cultures."

Eid al-Adha, Eid al-Fitr, the birth of the Prophet Muhammad, the Prophet's Ascension, the Islamic New Year, Christmas, and the Gregorian calendar New Year are celebrated as national holidays. Christians may request leave for other Christian holidays approved by the local Council of Bishops such as Easter and Palm Sunday.

There were no reports that the practice of any faith was prohibited; however, the Government does not officially recognize all religious groups. Some religious groups, while allowed to meet and practice their faith, faced societal and official discrimination. In addition, not all Christian denominations have applied for or been accorded legal recognition.

The Government does not recognize the Druze or Baháʼí Faiths as religions but does not prohibit their practice. The Druze do not face official discrimination nor do they complain of social discrimination. Baháʼís face both official and social discrimination. The Baháʼí community does not have its own court to adjudicate personal status matters, such as inheritance and other family-related issues; such cases may be heard in Shari'a courts. Baháʼí spouses face difficulty in obtaining residency permits for their non-Jordanian partners because the Government does not recognize Baháʼí marriage certificates. The Government does not officially recognize the Druze temple in Azraq, and four social halls belonging to the Druze are registered as "societies." The Government does not permit Baháʼís to register schools or places of worship. The Baháʼí cemetery in Adasieh is registered in the name of the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs.

Employment applications for government positions occasionally contain questions about an applicant's religion. Christians serve regularly as cabinet ministers. Of the 120 seats of the lower house of Parliament, 9 are reserved for Christians. No seats are reserved for adherents of other religious groups. No seats are reserved for Druze, but they are permitted to hold office under their government classification as Muslims.

The Government does not recognize Jehovah's Witnesses, or the Church of Christ, but each is allowed to conduct religious services without interference.

The Government recognizes Judaism as a religion; however, there are reportedly no citizens who are Jewish. The Government does not impose restrictions on Jews, and they are permitted to own property and conduct business in the country.

Because Shari'a governs the personal status of Muslims, converting from Islam to Christianity and proselytism of Muslims are not allowed. Muslims who convert to another religion face societal and governmental discrimination. Under Shari'a, converts are regarded as apostates and may be denied their civil and property rights. The Government maintains it neither encourages nor prohibits apostasy. The Government does not recognize converts from Islam as falling under the jurisdiction of their new religious community's laws in matters of personal status; converts are still considered Muslims. Converts to Islam fall under the jurisdiction of Shari'a courts. Shari'a, in theory, provides for the death penalty for Muslims who apostatize; however, the Government has never applied such punishment. The Government allows conversion to Islam.

There is no statute that expressly forbids proselytism of Muslims; however, government policy requires that foreign missionary groups refrain from public proselytism.

The Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary (JETS), a Christian training school for pastors and missionaries, was registered with the Government and operates as a cultural center. JETS purchased land to build a new facility in 2003 and received permits to construct the buildings in September 2006. JETS is permitted to appoint faculty and administration, but the Government denies accreditation as an academic institution. Because JETS is not accredited, its students are not eligible for student visas but may enter the country on tourist visas of limited duration. The JETS program requires four years of study, and as a consequence many students overstay their visas; upon departure from the country they, and any family members who may have accompanied them, are required to pay two dollars for each day they spent without a visa (as are other visiting foreign nationals). The Government does not allow JETS to accept Muslim students.

According to JETS, during the reporting period the Government revoked JETS's nonprofit status, requiring the organization to pay 16 percent sales tax on all items purchased. In 2006, the Customs office confiscated a shipment of approximately 100 books ordered by JETS. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs intervened and secured the release of the books.

Parliamentary elections law historically has under represented urban areas that are centers of support for Islamist candidates.

The Political Parties Law prohibits houses of worship from being used for political activity. This stipulation was designed primarily to prevent government opponents from preaching politically oriented sermons in mosques.

The Ministry of Religious Affairs and Trusts ("Awqaf") manages Islamic institutions and the construction of mosques. It also appoints imams, provides mosque staff salaries, manages Islamic clergy training centers, and subsidizes certain activities sponsored by mosques. The Government monitors sermons at mosques and requires that preachers refrain from political commentary that could instigate social or political unrest.

Following the Summer 2006 Lebanon war, some Sunnis in the country reportedly converted to Shi'ism. In November 2006, the Government reportedly deported some Iraqi Shi'ites for practicing self-flagellation rituals at a Shi'ite shrine outside Amman. Some Sunni clerics alleged that Iraqi Shi'ites could be Iranian agents, and some sources reported that the alleged deportations were a result of Shi'a proselytizing. The credibility of these reports was not verified. The Government permits Shi'ites to worship but not to self-mutilate or to shed blood, as may occur in some Shi'ite ceremonies.

In January 2006, Jihad Al-Momani, former chief editor of the weekly newspaper Shihan, and Hussein Al-Khalidi, of the weekly Al-Mihar, were arrested for printing controversial cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. On February 5, 2006, the two men were charged by the Conciliation Court and the Court of First Instance with "denigrating the Prophets in public" and "insulting God." In May 2006 they received the minimum prison sentence of two months, but were immediately released on bail with the possibility that the sentences would be commuted to a light fine of $170 (JD 120) each.

Druze, Baháʼís, and members of other unrecognized religious groups do not have their religious affiliations correctly noted on their national identity cards or "family books" (the family book is a national registration record that is issued to the head of every family and that serves as proof of citizenship). Baháʼís have an "assembly" which officiates marriages; however, the Department of Civil Status and Passports (DCSP) does not recognize marriages conducted by Baháʼí assemblies, and will not issue birth certificates for the children of these marriages or residence permits for partners who are not citizens. The DCSP issues passports on the basis of these marriages, but without entering the marriage into official records. The DCSP frequently records Baháʼís and Druze as Muslims on identifying documents. Atheists must associate themselves with a recognized religion for purposes of official identification.

The Government traditionally reserves some positions in the upper levels of the military for Christians (4 percent); however, all senior command positions are held by Muslims. Division-level commanders and above are required to lead Islamic prayer on certain occasions. There is no Christian clergy in the military.

On April 29, 2007, government authorities reportedly deported Pastor Mazhar Izzat Bishay of the Aqaba Free Evangelical Church, an Egyptian national and long-time resident, to Egypt. It was reported that they had previously interrogated him and that they offered him no reason for his deportation. At the end of the reporting period, the credibility of these reports had not been verified.

In November 2006, the authorities deported Wajeeh Besharah, Ibrahim Atta, Raja Welson, Imad Waheeb, four Coptic Egyptians living in Aqaba, to Egypt. It was reported that the authorities questioned them about their affiliation with the Free Evangelical Church in Aqaba prior to their deportation. At the end of the reporting period, the credibility of this report had not been verified.

On January 20, 2006, a Shari'a court received an apostasy complaint against Mahmoud Abdel Rahman Mohammad Eleker, a convert from Islam to Christianity. On April 14, 2006, the complainant, the convert's brother-in-law, dropped the charges after the convert's wife renounced in the presence of a lawyer any claims she might have to an inheritance from her own parents. At the end of the reporting period, there was no further update on this case.

In September 2004, on the order of a Shari'a court, the authorities arrested a convert from Islam to Christianity and held him overnight on charges of apostasy. In November 2004, a Shari'a court found the defendant guilty of apostasy. The ruling was upheld in January 2005 by a Shari'a appeals court. The verdict declared the convert to be a ward of the state, stripped him of his civil rights, and annulled his marriage. It further declared him to be without any religious identity. It stated that he lost all rights to inheritance and may not remarry his (now former) wife unless he returns to Islam, and forbade his being considered an adherent of any other religion. The verdict implies the possibility that legal and physical custody of his child could be assigned to someone else. The convert left the country, received refugee status, and was resettled in the United States.

There were no reports of religious prisoners or detainees who remained in custody at the end of the period covered by this report.

There were no reports of forced religious conversion, including of U.S. citizens who had been abducted or illegally removed from the United States, or of the refusal to allow such citizens to be returned to the United States.

Editorial cartoons, articles, and opinion pieces with antisemitic themes occur with less frequency in the government-controlled media, but are more common and feature more prominently in privately owned weekly tabloids such as al-Sabil and al-Rai. [6]

In 2022, the al-Rai newspaper printed several articles containing antisemitic content and denying the Holocaust. [1]

On December 26, 2006, King Abdullah II convened his first meeting with evangelical leaders. Attendees reported that this event offered a sense of hope and progress towards continued interfaith dialogue.

The Baptist Church applied for official registration with the Ministry of Interior on December 12, 2006. In June 2006, the Prime Ministry denied the Church's application. No additional information regarding the reason for denial was available by the end of the reporting period. The Assemblies of God Church also applied for official registration with the Ministry of Interior on April 10, 2007. Its application was under consideration at the end of the period covered by this report.

In June 2006, the Government published the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in the Official Gazette. Article 18 of the Covenant provides for freedom of religion.

Baháʼís faced some societal discrimination.

Muslims who convert to other religions often face social ostracism, threats, and abuse from their families and Muslim religious leaders. According to the survey in 2010 by the Pew Global Attitudes Project, 86% of Jordanians polled supported the death penalty for those who leave the Muslim religion. [7]

Parents usually strongly discourage young adults from pursuing interfaith romantic relationships, because they may lead to conversion. Such relationships may lead to ostracism and, in some cases, violence against the couple or feuds between members of the couple's families. When such situations arise, families may approach local government officials for resolution. In the past, there were reports that in some cases local government officials encouraged Christian women involved in relationships with Muslim men to convert to Islam to defuse potential family or tribal conflict and keep the peace; however, during the period covered by this report, no such cases were reported.

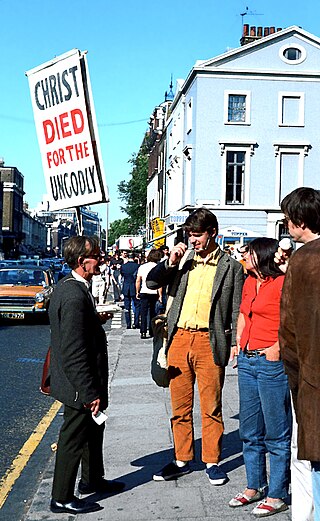

Proselytism is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Carrying out attempts to instill beliefs can be called proselytization.

The constitution of Iran states that the country is an Islamic republic; it specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion.

Religion in Israel is manifested primarily in Judaism, the ethnic religion of the Jewish people. The State of Israel declares itself as a "Jewish and democratic state" and is the only country in the world with a Jewish-majority population. Other faiths in the country include Islam, Christianity and the religion of the Druze people. Religion plays a central role in national and civil life, and almost all Israeli citizens are automatically registered as members of the state's 14 official religious communities, which exercise control over several matters of personal status, especially marriage. These recognized communities are Orthodox Judaism, Islam, the Druze faith, the Catholic Church, Greek Orthodox Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Armenian Apostolic Church, Anglicanism, and the Baháʼí Faith.

Religion in Egypt controls many aspects of social life and is endorsed by law. The state religion of Egypt is Islam, although estimates vary greatly in the absence of official statistics. Since the 2006 census, religion has been excluded, and thus available statistics are estimates made by religious and non-governmental agencies. The country is majority Sunni Muslim, with the next largest religious group being Coptic Orthodox Christians. The exact numbers are subject to controversy, with Christians alleging that they have been systemically under-counted in existing censuses.

Baháʼís are persecuted in various countries, especially in Iran, where the Baháʼí Faith originated and where one of the largest Baháʼí populations in the world is located. The origins of the persecution stem from a variety of Baháʼí teachings which are inconsistent with traditional Islamic beliefs, including the finality of Muhammad's prophethood, and the placement of Baháʼís outside the Islamic religion. Thus, Baháʼís are seen as apostates from Islam.

Sunni Islam is the dominant religion in Jordan. Muslims make up about 97.2% of the country's population. A few of them are Shiites. Many Shia in Jordan are refugees from Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

The Egyptian identification card controversy is a series of events, beginning in the 1990s, that created a de facto state of disenfranchisement for Egyptian Baháʼís, atheists, agnostics, and other Egyptians who did not identify themselves as Muslim, Christian, or Jewish on government identity documents.

Religion in Iran has been shaped by multiple religions and sects over the course of the country's history. Zoroastrianism was the main followed religion during the Achaemenid Empire, Parthian Empire, and Sasanian Empire. Another Iranian religion known as Manichaeanism was present in Iran during this period. Jewish and Christian communities thrived, especially in the territories of northwestern, western, and southern Iran—mainly Caucasian Albania, Asoristan, Persian Armenia, and Caucasian Iberia. A significant number of Iranian peoples also adhered to Buddhism in what was then eastern Iran, such as the regions of Bactria and Sogdia.

Nepal is a secular state under the Constitution of Nepal 2015, where "secular" means religious, cultural freedoms, including protection of religion and culture handed down from time immemorial.

The constitution of Brunei states that while the official religion is the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam, all other religions may be practiced "in peace and harmony." Apostasy and blasphemy are legally punishable by corporal and capital punishment, including stoning to death, amputation of hands or feet, or caning. Only caning has been used since 1957.

The Indonesian constitution provides some degree of freedom of religion. The government generally respects religious freedom for the six officially recognized religions and/or folk religion. All religions have equal rights according to the Indonesian laws.

The Constitution of Bahrain states that Islam is the official religion and that Shari'a is a principal source for legislation. Article 22 of the Constitution provides for freedom of conscience, the inviolability of worship, and the freedom to perform religious rites and hold religious parades and meetings, in accordance with the customs observed in the country; however, the Government has placed some limitations on the exercise of this right.

According to Article 9 of the Lebanese Constitution, all religions and creeds are to be protected and the exercise of freedom of religion is to be guaranteed providing that the public order is not disturbed. The Constitution declares equality of rights and duties for all citizens without discrimination or preference. Nevertheless, power is distributed among different religious and sectarian groups. The position of president is reserved for a Maronite Christian; the role of Presidency of Parliament for a Shiite Muslim; and the role of Prime Minister for a Sunni Muslim. The government has generally respected these rights; however, the National Pact agreement in 1943 restricted the constitutional provision for apportioning political offices according to religious affiliation. There have been periodic reports of tension between religious groups, attributable to competition for political power, and citizens continue to struggle with the legacy of the civil war that was fought along sectarian lines. Despite sectarian tensions caused by the competition for political power, the Lebanese continue to coexist.

In Qatar, the Constitution, as well as certain laws, provide for freedom of association, public assembly, and worship in accordance with the requirements of public order and morality. Notwithstanding this, the law prohibits proselytizing by non-Muslims and places some restrictions on public worship. Islam is the state religion.

The most widely professed religion in Bosnia and Herzegovina is Islam and the second biggest religion is Christianity. Nearly all the Muslims of Bosnia are followers of the Sunni denomination of Islam; the majority of Sunnis follow the Hanafi legal school of thought (fiqh) and Maturidi theological school of thought (kalām). Bosniaks are generally associated with Islam, Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Roman Catholic Church, and Bosnian Serbs with the Serbian Orthodox Church. The State Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the entity Constitutions of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska provide for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respects this right in ethnically integrated areas or in areas where government officials are of the majority religion; the state-level Law on Religious Freedom also provides comprehensive rights to religious communities. However, local authorities sometimes restricted the right to worship of adherents of religious groups in areas where such persons are in the minority.

Of the religions in Tunisia, Islam is the most prevalent. It is estimated that in 2022, approximately 99% of Tunisia's inhabitants identified themselves as Muslims.

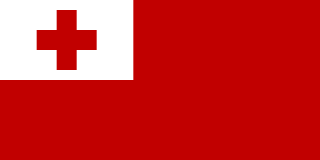

Christianity is the predominant religion in Tonga, with Methodists having the most adherents.

Freedom of religion in Morocco refers to the extent to which people in Morocco are freely able to practice their religious beliefs, taking into account both government policies and societal attitudes toward religious groups. The constitution declares that Islam is the religion of the state, with the state guaranteeing freedom of thought, expression, and assembly. The state religion of Morocco is Islam. The government plays an active role in determining and policing religious practice for Muslims, and disrespecting Islam in public can carry punishments in the forms of fines and imprisonment.

The status of religious freedom in Africa varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

The status of religious freedom in Asia varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.