Monosaccharides, also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built. Simply, this is the structural unit of carbohydrates.

In chemistry, a pentose is a monosaccharide with five carbon atoms. The chemical formula of many pentoses is C

5H

10O

5, and their molecular weight is 150.13 g/mol.

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. This contrasts with structural isomers, which share the same molecular formula, but the bond connections or their order differs. By definition, molecules that are stereoisomers of each other represent the same structural isomer.

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is C6H12O6, and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

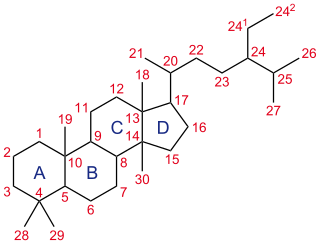

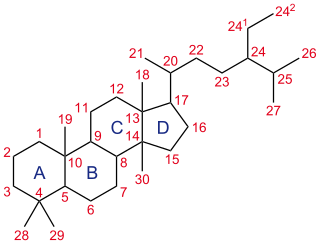

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

The structural formula of a chemical compound is a graphic representation of the molecular structure, showing how the atoms are possibly arranged in the real three-dimensional space. The chemical bonding within the molecule is also shown, either explicitly or implicitly. Unlike other chemical formula types, which have a limited number of symbols and are capable of only limited descriptive power, structural formulas provide a more complete geometric representation of the molecular structure. For example, many chemical compounds exist in different isomeric forms, which have different enantiomeric structures but the same molecular formula. There are multiple types of ways to draw these structural formulas such as: Lewis structures, condensed formulas, skeletal formulas, Newman projections, Cyclohexane conformations, Haworth projections, and Fischer projections.

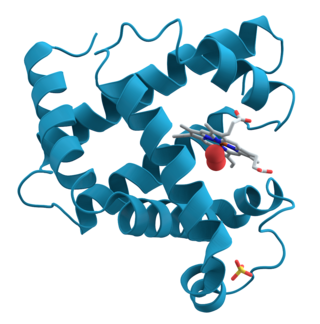

A biomolecule or biological molecule is loosely defined as a molecule produced by a living organism and essential to one or more typically biological processes. Biomolecules include large macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids, as well as small molecules such as vitamins and hormones. A more general name for this class of material is biological materials. Biomolecules are an important element of living organisms, those biomolecules are often endogenous, produced within the organism but organisms usually need exogenous biomolecules, for example certain nutrients, to survive.

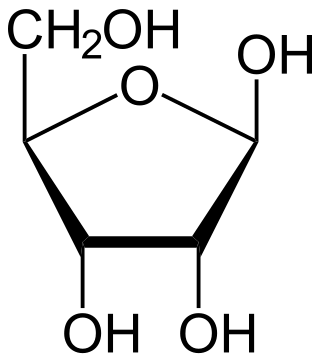

In chemistry, a Haworth projection is a common way of writing a structural formula to represent the cyclic structure of monosaccharides with a simple three-dimensional perspective. Haworth projection approximate the shapes of the actual molecules better for furanoses—which are in reality nearly planar—than for pyranoses which exist in solution in the chair conformation. Organic chemistry and especially biochemistry are the areas of chemistry that use the Haworth projection the most.

In carbohydrate chemistry, a pair of anomers is a pair of near-identical stereoisomers or diastereomers that differ at only the anomeric carbon, the carbon atom that bears the aldehyde or ketone functional group in the sugar's open-chain form. However, in order for anomers to exist, the sugar must be in its cyclic form, since in open-chain form, the anomeric carbon atom is planar and thus achiral. More formally stated, then, an anomer is an epimer at the hemiacetal/hemiketal carbon atom in a cyclic saccharide. Anomerization is the process of conversion of one anomer to the other. As is typical for stereoisomeric compounds, different anomers have different physical properties, melting points and specific rotations.

Glycal is a name for cyclic enol ether derivatives of sugars having a double bond between carbon atoms 1 and 2 of the ring. The term "glycal" should not be used for an unsaturated sugar that has a double bond in any position other than between carbon atoms 1 and 2.

In organic chemistry, the anomeric effect or Edward-Lemieux effect is a stereoelectronic effect that describes the tendency of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to a heteroatom within a cyclohexane ring to prefer the axial orientation instead of the less-hindered equatorial orientation that would be expected from steric considerations. This effect was originally observed in pyranose rings by J. T. Edward in 1955 when studying carbohydrate chemistry.

In organic chemistry, pyranose is a collective term for saccharides that have a chemical structure that includes a six-membered ring consisting of five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. There may be other carbons external to the ring. The name derives from its similarity to the oxygen heterocycle pyran, but the pyranose ring does not have double bonds. A pyranose in which the anomeric −OH at C(l) has been converted into an OR group is called a pyranoside.

A cyclic compound is a term for a compound in the field of chemistry in which one or more series of atoms in the compound is connected to form a ring. Rings may vary in size from three to many atoms, and include examples where all the atoms are carbon, none of the atoms are carbon, or where both carbon and non-carbon atoms are present. Depending on the ring size, the bond order of the individual links between ring atoms, and their arrangements within the rings, carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds may be aromatic or non-aromatic; in the latter case, they may vary from being fully saturated to having varying numbers of multiple bonds between the ring atoms. Because of the tremendous diversity allowed, in combination, by the valences of common atoms and their ability to form rings, the number of possible cyclic structures, even of small size numbers in the many billions.

Carbohydrate conformation refers to the overall three-dimensional structure adopted by a carbohydrate (saccharide) molecule as a result of the through-bond and through-space physical forces it experiences arising from its molecular structure. The physical forces that dictate the three-dimensional shapes of all molecules—here, of all monosaccharide, oligosaccharide, and polysaccharide molecules—are sometimes summarily captured by such terms as "steric interactions" and "stereoelectronic effects".

Oligosaccharides and polysaccharides are an important class of polymeric carbohydrates found in virtually all living entities. Their structural features make their nomenclature challenging and their roles in living systems make their nomenclature important.

Monosaccharide nomenclature is the naming system of the building blocks of carbohydrates, the monosaccharides, which may be monomers or part of a larger polymer. Monosaccharides are subunits that cannot be further hydrolysed in to simpler units. Depending on the number of carbon atom they are further classified into trioses, tetroses, pentoses, hexoses etc., which is further classified in to aldoses and ketoses depending on the type of functional group present in them.

Carbohydrate NMR spectroscopy is the application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to structural and conformational analysis of carbohydrates. This method allows the scientists to elucidate structure of monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, polysaccharides, glycoconjugates and other carbohydrate derivatives from synthetic and natural sources. Among structural properties that could be determined by NMR are primary structure, saccharide conformation, stoichiometry of substituents, and ratio of individual saccharides in a mixture. Modern high field NMR instruments used for carbohydrate samples, typically 500 MHz or higher, are able to run a suite of 1D, 2D, and 3D experiments to determine a structure of carbohydrate compounds.

Kalkitoxin, a toxin derived from the cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula, induces NMDA receptor mediated neuronal necrosis, blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels, and induces cellular hypoxia by inhibiting the electron transport chain (ETC) complex 1.

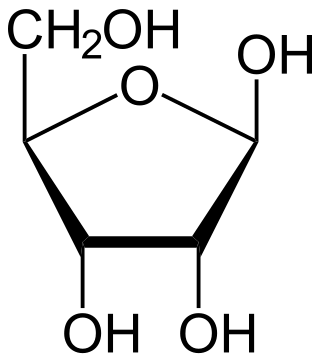

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, d-ribose, is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compound is necessary for coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. It has a structural analog, deoxyribose, which is a similarly essential component of DNA. l-ribose is an unnatural sugar that was first prepared by Emil Fischer and Oscar Piloty in 1891. It was not until 1909 that Phoebus Levene and Walter Jacobs recognised that d-ribose was a natural product, the enantiomer of Fischer and Piloty's product, and an essential component of nucleic acids. Fischer chose the name "ribose" as it is a partial rearrangement of the name of another sugar, arabinose, of which ribose is an epimer at the 2' carbon; both names also relate to gum arabic, from which arabinose was first isolated and from which they prepared l-ribose.

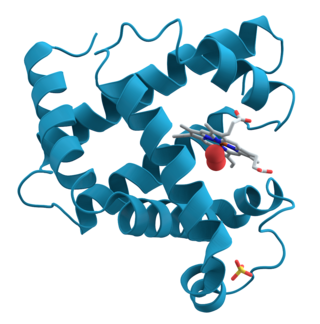

D-Ribose pyranase is an enzyme that catalyzes the interconversion of β-D-ribopyranose and β-D-ribofuranose. This enzyme is an isomerase that has only been found in bacteria and viruses. It has two known functions of helping transport ribose into cells and producing β-D-ribofuranose, which can later be used to make ribose 5-phosphate for the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). D-Ribose pyranase does not have a defined crystal structure but there are two different proposed structures. The active site of D-ribose pyranase is high in histidine residues along with a few other key binding sites.