Related Research Articles

Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Marr was a German agitator and journalist, who popularized the term "antisemitism" (1881) [which was invented by Moritz Steinschneider].

Julius Streicher was a member of the Nazi Party, the Gauleiter of Franconia and a member of the Reichstag, the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, which became a central element of the Nazi propaganda machine. The publishing firm was financially very successful and made Streicher a multi-millionaire.

The German National People's Party was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Weimar Germany. It was an alliance of conservative, nationalists, reactionary monarchists, völkisch and antisemitic elements supported by the Pan-German League.

The Free Conservative Party was a liberal-conservative political party in Prussia and the German Empire which emerged from the Prussian Conservative Party in the Prussian Landtag in 1866. In the federal elections to the Reichstag parliament from 1871, it ran as the German Reich Party. DRP was classified as centrist or centre-right by political standards at the time, and it also put forward the slogan "conservative progress".

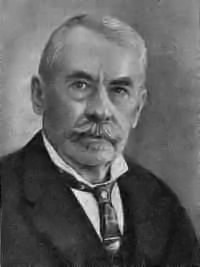

Theodor Fritsch, was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His writings also appeared under the pen names Thomas Frey, Fritz Thor, and Ferdinand Roderich-Stoltheim.

Count Sándor Ágost Dénes Festetics de Tolna was a Hungarian nobleman and cabinet minister who later became an advocate of Nazism in Hungary.

The Christian Social Party was a right-wing political party in the German Empire founded in 1878 by Adolf Stoecker as the Christian Social Workers' Party.

Benno Jacob was a liberal rabbi and Bible scholar.

Ludwig Johannes Herbert Martin Münchmeyer was an Evangelical German pastor known for antisemitism. He led an "antisemitic spa" on the island of Borkum. He won a libel suit against Bruno Weil, but enough of the allegations of loose morals and scandalous misconduct against him were confirmed that he was defrocked. He later acted as a prominent Nazi speaker after leaving the German National People's Party. He also propagandized for the Nazi Party in Weser-Ems.

The Pan-German League was a Pan-German nationalist organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed.

Otto Böckel was a German populist politician who became one of the first to successfully exploit anti-Semitism as a political issue in the country.

Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg was a German officer who became noted as an anti-Semitic politician and publisher. He was part of a wider campaign against German Jews that became a central feature of nationalist politics in Imperial Germany in the late nineteenth century.

Hermann Ahlwardt was a writer, a member of the Reichstag and a vehement antisemite.

Antisemitism in Russia is expressed in acts of hostility against Jews in Russia and the promotion of antisemitic views in the Russian Federation. This article covers the events since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Previous time periods are covered in the articles Antisemitism in the Russian Empire and Antisemitism in the Soviet Union.

Anti-Jewish boycotts are organized boycotts directed against Jewish people to exclude them economical, political or cultural life. Antisemitic boycotts are often regarded as a manifestation of popular antisemitism.

The Economic Union was a parliamentary group in the German Empire's Reichstag, gathering deputies of several minor antisemitic and agrarian parties.

The German Social Party was a far-right political party active in the German Empire.

The German Reform Party was a far-right political party active in the German Empire. It had antisemitism as its ideological basis.

Oswald Franz Alexander Zimmermann was a German anti-Semitic politician and journalist. One of the leading representatives of political anti-Semitism in the German Empire, he was elected a member of the Reichstag three times.

Anti-antisemitism is opposition to antisemitism or prejudice against Jews, and just like the history of antisemitism, the history of anti-antisemitism is long and multifaceted. According to historian Omer Bartov, political controversies around antisemitism involve "those who see the world through an antisemitic prism, for whom everything that has gone wrong with the world, or with their personal lives, is the fault of the Jews; and those who see the world through an anti-antisemitic prism, for whom every critical observation of Jews as individuals or as a community, or, most crucially, of the state of Israel, is inherently antisemitic". It is disputed whether or not anti-antisemitism is synonymous with philosemitism, but anti-antisemitism often includes the "imaginary and symbolic idealization of ‘the Jew’" which is similar to philosemitism.

References

- ↑ Geoff Eley, Reshaping the German Right: Radical Nationalism and Political Change After Bismarck, University of Michigan Press, 1991, p. 246

- 1 2 Robert Melson, Revolution and Genocide: On the Origins of the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust, University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 118

- ↑ Dan S. White, The Splintered Party: National Liberalism in Hessen and the Reich, 1867-1918, 1976, p. 146

- ↑ Herbert A. Strauss, Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Walter de Gruyter, 1993, p. 142

- ↑ Jack Wertheimer, Unwelcome Strangers, Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 165

- ↑ Heinrich August Winkler, Germany: 1789-1933, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 254

- ↑ Carola Daffner, Beth A. Muellner, German Women Writers and the Spatial Turn: New Perspectives, Walter de Gruyter, 2015, pp. 225-226

- ↑ Gary D. Stark, Banned In Berlin: Literary Censorship in Imperial Germany, 1871-1918, Berghahn Books, 2013, pp. 61-62

- ↑ David Cesarani, Sarah Kavanaugh, Holocaust: Hitler, Nazism and the "Racial State", Psychology Press, 2004, p. 78

- ↑ Strauss, Hostages of Modernization, p. 72

- ↑ Richard S. Levy, Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 22

- ↑ Jonathan Karp, Adam Sutcliffe, Philosemitism in History, Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 172

- ↑ Madeleine Hurd, Public Spheres, Public Mores, and Democracy: Hamburg and Stockholm, 1870-1914, University of Michigan Press, 2000, p. 75

- ↑ Hurd, Public Spheres, Public Mores, and Democracy, pp. 178-179

- ↑ Peter G. J. Pulzer, The Rise of Political Anti-semitism in Germany & Austria, Harvard University Press, 1988, p. 44

- ↑ Strauss, Hostages of Modernization, p. 76

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 762 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914-45, Routledge, 2001, p. 57

- ↑ Strauss, Hostages of Modernization, p. 147

- ↑ Rudy J. Koshar, Social Life, Local Politics, and Nazism: Marburg, 1880-1935, UNC Press Books, 2014, p. 71

- ↑ Larry Eugene Jones, The German Right in the Weimar Republic: Studies in the History of German Conservatism, Nationalism, and Antisemitism, Berghahn Books, 2014, p. 80

- ↑ Walther Killy (ed.), Dictionary of German Biography: Thibaut - Zycha, Volume 10, Walter de Gruyter, 2006, p. 705