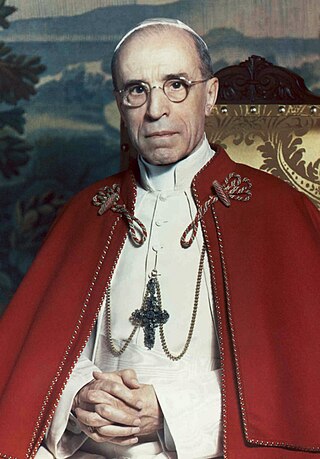

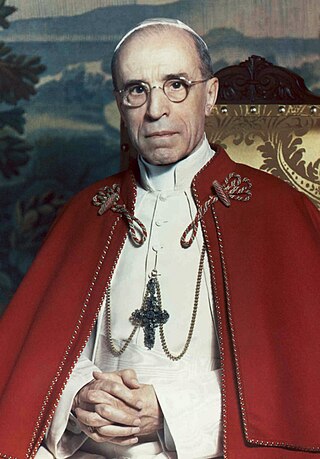

Pope Pius XII was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his election to the papacy, he served as secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, papal nuncio to Germany, and Cardinal Secretary of State, in which capacity he worked to conclude treaties with various European and Latin American nations, including the Reichskonkordat treaty with the German Reich.

The Lateran Treaty was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman Question. The treaty and associated pacts were named after the Lateran Palace where they were signed on 11 February 1929, and the Italian parliament ratified them on 7 June 1929. The treaty recognised Vatican City as an independent state under the sovereignty of the Holy See. The Italian government also agreed to give the Roman Catholic Church financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States. In 1948, the Lateran Treaty was recognized in the Constitution of Italy as regulating the relations between the state and the Catholic Church. The treaty was significantly revised in 1984, ending the status of Catholicism as the sole state religion.

Pope Pius XI, born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was the Bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to 10 February 1939. He also became the first sovereign of the Vatican City State upon its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929. He remained head of the Catholic Church until his death in February 1939. His papal motto was "Pax Christi in Regno Christi", translated as "The Peace of Christ in the Reign of Christ".

The Reichskonkordat is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII, on behalf of Pope Pius XI and Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen on behalf of President Paul von Hindenburg and the German government. It was ratified 10 September 1933 and it has been in force from that date onward. The treaty guarantees the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. When bishops take office Article 16 states they are required to take an oath of loyalty to the Governor or President of the German Reich established according to the constitution. The treaty also requires all clergy to abstain from working in and for political parties. Nazi breaches of the agreement began almost as soon as it had been signed and intensified afterwards leading to protest from the Church including in the 1937 Mit brennender Sorge encyclical of Pope Pius XI. The Nazis planned to eliminate the Church's influence by restricting its organizations to purely religious activities.

Mit brennender Sorge is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937. Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was smuggled into Germany for fear of censorship and was read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches on one of the Church's busiest Sundays, Palm Sunday.

Pietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

The Catholic Church in Germany or Roman Catholic Church in Germany is part of the worldwide Roman Catholic Church in communion with the Pope, assisted by the Roman Curia, and with the German bishops. The current "Speaker" of the episcopal conference is Georg Bätzing, Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Limburg. It is divided into 27 dioceses, 7 of them with the rank of metropolitan sees.

The Church policies after World War II of Pope Pius XII focused on material aid to war-torn Europe, the internationalization of the Roman Catholic Church, its persecution in Eastern Europe, China and Vietnam, and relations with the United States and the emerging European Union.

Kirchenkampf is a German term which pertains to the situation of the Christian churches in Germany during the Nazi period (1933–1945). Sometimes used ambiguously, the term may refer to one or more of the following different "church struggles":

- The internal dispute within German Protestantism between the German Christians and the Confessing Church over control of the Protestant churches;

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Protestant church bodies; and

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Roman Catholic Church.

Persecutions against the Catholic Church took place during the papacy of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). Pius' reign coincided with World War II (1939–1945), followed by the commencement of the Cold War and the accelerating European decolonisation. During his papacy, the Catholic Church faced persecution under Fascist and Communist governments.

Pope Pius XII and Poland includes Church relations from 1939 to 1958. Pius XII became Pope on the eve of the Second World War. The invasion of predominantly Catholic Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939 ignited the conflict and was followed soon after by a Soviet invasion of the Eastern half of Poland, in accordance with an agreement reached between the dictators Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. The Catholic Church in Poland was about to face decades of repression, both at Nazi and Communist hands. The Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Poland was followed by a Stalinist repression which was particularly intense through the years 1946–1956. Pope Pius XII's policies consisted in attempts to avoid World War II, extensive diplomatic activity on behalf of Poland and encouragement to the persecuted clergy and faithful.

The tradition of the Catholic Church claims it began with Jesus Christ and his teachings; the Catholic tradition considers that the Church is a continuation of the early Christian community established by the Disciples of Jesus. The Church considers its bishops to be the successors to Jesus's apostles and the Church's leader, the Bishop of Rome, to be the sole successor to St Peter who ministered in Rome in the first century AD after his appointment by Jesus as head of the Church. By the end of the 2nd century, bishops began congregating in regional synods to resolve doctrinal and administrative issues. Historian Eamon Duffy claims that by the 3rd century, the church at Rome might even function as a court of appeal on doctrinal issues.

Cesare Vincenzo Orsenigo was Apostolic Nuncio to Germany from 1930 to 1945, during the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II. Along with the German ambassador to the Vatican, Diego von Bergen and later Ernst von Weizsäcker, Orsenigo was the direct diplomatic link between Pope Pius XI and Pope Pius XII and the Nazi regime, meeting several times with Adolf Hitler directly and frequently with other high-ranking officials and diplomats.

The papacy of Pius XII began on 2 March 1939 and continued to 9 October 1958, covering the period of the Second World War and the Holocaust, during which millions of Jews were murdered by Adolf Hitler's Germany. Before becoming pope, Cardinal Pacelli served as a Vatican diplomat in Germany and as Vatican Secretary of State under Pius XI. His role during the Nazi period has been closely scrutinised and criticised. His supporters argue that Pius employed diplomacy to aid the victims of the Nazis during the war and, through directing his Church to provide discreet aid to Jews and others, saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Pius maintained links to the German Resistance, and shared intelligence with the Allies. His strongest public condemnation of genocide was, however, considered inadequate by the Allied Powers, while the Nazis viewed him as an Allied sympathizer who had dishonoured his policy of Vatican neutrality.

Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany differed in their responses to the rise of Nazi Germany, World War II, and the Holocaust during the years 1933–1945. In the 1930s, the Episcopate of the Catholic Church of Germany comprised 6 Archbishops and 19 bishops while German Catholics comprised around one third of the population of Germany served by 20,000 priests. In the lead up to the 1933 Nazi takeover, German Catholic leaders were outspoken in their criticism of Nazism. Following the Nazi takeover, the Catholic Church sought an accord with the Government, was pressured to conform, and faced persecution. The regime had flagrant disregard for the Reich concordat with the Holy See, and the episcopate had various disagreements with the Nazi government, but it never declared an official sanction of the various attempts to overthrow the Hitler regime. Ian Kershaw wrote that the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of ... especially of the Catholic Church - against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.

The conversion of Jews to Catholicism during the Holocaust is one of the most controversial aspects of the record of Pope Pius XII during The Holocaust.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

During the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), the Weimar Republic transitioned into Nazi Germany. In 1933, the ailing President von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany in a Coalition Cabinet, and the Holy See concluded the Reich concordat treaty with the still nominally functioning Weimar state later that year. Hoping to secure the rights of the Church in Germany, the Church agreed to a requirement that clergy cease to participate in politics. The Hitler regime routinely violated the treaty, and launched a persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany.

The Roman Catholic Church in the 20th century responded to the challenge of increasing secularization of Western society and persecution resulting from great social unrest and revolutions in several countries. It instituted reforms, particularly in the 1970s after the Second Vatican Council, to modernize practices and positions. In this period, Catholic missionaries in the Far East worked to improve education and health care, while evangelizing peoples and attracting followers in China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan.

Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany was a component of German resistance to Nazism and of Resistance during World War II. The role of the Catholic Church during the Nazi years remains a matter of much contention. From the outset of Nazi rule in 1933, issues emerged which brought the church into conflict with the regime and persecution of the church led Pope Pius XI to denounce the policies of the Nazi Government in the 1937 papal encyclical Mit brennender Sorge. His successor Pius XII faced the war years and provided intelligence to the Allies. Catholics fought on both sides in World War II and neither the Catholic nor Protestant churches as institutions were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi State.