Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The town's population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia meet, it is the easternmost town in West Virginia as well as its lowest point above sea level.

The St. Louis Arsenal is a large complex of federal military weapons and ammunition storage buildings operated by the United States Air Force in St. Louis, Missouri. During the American Civil War, the St. Louis arsenal's contents were transferred to Illinois by Union Captain Nathaniel Lyon, an act that helped fuel tension between secessionists and those citizens loyal to the Federal government.

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes the historic center of Harpers Ferry, notable as a key 19th-century industrial area and as the scene of John Brown's failed abolitionist uprising. It contains the most visited historic site in the state of West Virginia, John Brown's Fort.

John Brown's Fort was initially built in 1848 for use as a guard and fire engine house by the federal Harpers Ferry Armory, in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. An 1848 military report described the building as "An engine and guard-house 35 1/2 x 24 feet, one story brick, covered with slate, and having copper gutters and down spouts…"

Virginius Island is a formerly inhabited island of some 12 acres (4.9 ha), on the Shenandoah River in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The island was created by the Shenandoah Canal, constructed by the Patowmack Company between 1806 and 1807, which separates it from the town of Harpers Ferry. The canal was constructed to enable boats to bypass rapids on the river, and also channel water to drive machinery. In the nineteenth century Virginius Island contained Harpers Ferry's industry and working-class housing: a boarding house and row houses. Virginius Island is part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

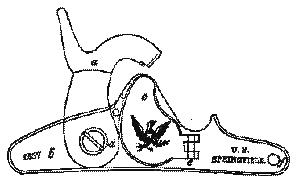

The Fayetteville Rifle was a 2 banded rifle produced at the Confederate States Arsenal in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The machinery which produced these weapons was primarily that captured at the United States Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, which was previously used to produce the US Model 1855 Rifle.

The 5th Vermont Infantry Regiment was a three years' infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Organized at St. Albans and mustered in September 16, 1861, it served in the Army of the Potomac (AoP). It departed Vermont for Washington, DC, September 23, 1861.

The city of Winchester, Virginia, and the surrounding area, were the site of numerous battles during the American Civil War, as contending armies strove to control the lower Shenandoah Valley. Winchester changed hands more often than any other Confederate city.

The 4th New York Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It is also known as the 1st Scott's Life Guard.

The 7th New York Infantry Regiment, later reorganized at the 7th Veteran Infantry Regiment, was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was composed almost entirely of German immigrants and is also known as the Steuben Guard or the Steuben Regiment. It should not be confused with the 7th New York Militia, an entirely different regiment whose service overlapped with the 7th New York Volunteers.

James H. Burton was born in Shenandoah Spring, Virginia. Educated at the Westchester Academy in Pennsylvania, Burton entered a Baltimore machine shop at age 16. In April 1844, he went to work at the Harpers Ferry Armory, serving as a machinist. He subsequently served as Foreman of the Rifle Factory Machine Shop, where he gained a considerable amount of knowledge and respect for the work of John H. Hall. Hall pioneered mechanized arms production and interchangeable manufacture at Harpers Ferry between 1820-1840. According to Burton, Hall's Rifle Works housed "not an occasional machine, but a plant of milling machinery by which the system and economy of the manufacture was materially altered." During the next three decades, Burton followed Hall's example by furthering the mechanization of arms production.

The Potomac Water Gap is a double water gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains, located at the intersection of the states of Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland, near Harpers Ferry. At 256 feet (78 m), it is the lowest crossing of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The Richmond rifle was a rifled musket produced by the Richmond Armory in Richmond, Virginia, for use by the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

The B & O Railroad Potomac River Crossing is a 15-acre (6.1 ha) historic site where a set of railroad bridges, originally built by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, span the Potomac River between Sandy Hook, Maryland and Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 14, 1978, for its significance in commerce, engineering, industry, invention, and transportation.

The Harpers Ferry Historic District comprises about one hundred historic structures in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The historic district includes the portions of the central town not included in Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, including large numbers of early 19th-century houses built by the United States Government for the workers at the Harpers Ferry Armory. Significant buildings and sites include the site of the Armory, the U.S Armory Potomac Canal, the Harpers Ferry Train Station, and Shenandoah Street, Potomac Street, and High or Washington Street. The National Historic Park essentially comprises the lower, flood-prone areas of the town, while the Historic District comprises the upper town.

The Winchester and Potomac Railroad (W&P) was a railroad in the southern United States, which ran from Winchester, Virginia, to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on the Potomac River, at a junction with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). It played a key role in early train raids of the B&O during the beginning months of the American Civil War.

The 2nd Virginia Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment raised in today's western Virginia and what became West Virginia during the American Civil War for service in the Confederate States Army. It would combine with the 4th, 5th, 27th, and 33rd Virginia infantry regiments and the Rockbridge Artillery Battery and fight as part of what became known as the Stonewall Brigade, mostly with the Army of Northern Virginia.

The Springfield Model 1855 was a rifled musket widely used in the American Civil War. It exploited the advantages of the new conical Minié ball, which could be deadly at over 1,000 yards (910 m). It was a standard infantry weapon for Union and Confederates alike, until the Springfield Model 1861 supplanted it, obviating the use of the insufficiently weather resistant Maynard tape primer.

The Virginia Manufactory of Arms was a state-owned firearms manufacturer and arsenal in what is today Richmond, Virginia. It was established by the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1798 to supply the Virginia militia with firearms and related items such as swords and bayonets. The factory originally operated from 1802 or 1803 to 1821.

The 49th New York Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.