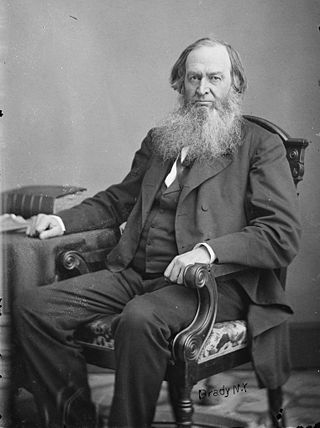

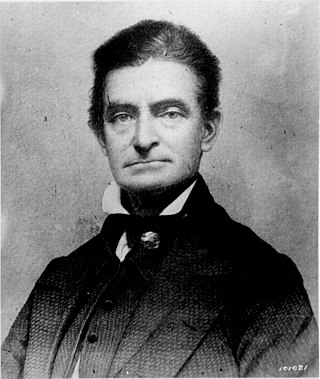

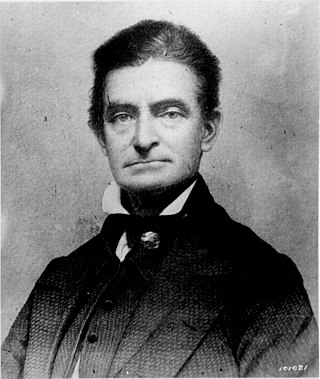

John Brown was a prominent leader in the American abolitionist movement in the decades preceding the Civil War. First reaching national prominence in the 1850s for his radical abolitionism and fighting in Bleeding Kansas, Brown was captured, tried, and executed by the Commonwealth of Virginia for a raid and incitement of a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

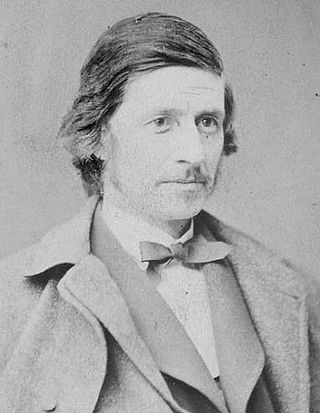

Samuel Gridley Howe was an American physician, abolitionist, and advocate of education for the blind. He organized and was the first director of the Perkins Institution. In 1824, he had gone to Greece to serve in the revolution as a surgeon; he also commanded troops. He arranged for support for refugees and brought many Greek children back to Boston with him for their education.

Mary Ann Day Brown was the second wife of abolitionist John Brown, leader of a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, which attempted to start a campaign of liberating enslaved people in the South. Married at age 17, Mary raised 5 stepchildren and an additional 13 children born during her marriage. She supported her husband's activities by managing the family farm while he was away, which he often was. Mary and her husband helped enslaved Africans escape slavery via the Underground Railroad. The couple lived in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and in the abolitionist settlement of North Elba, New York. After the execution of her husband, she became a California pioneer.

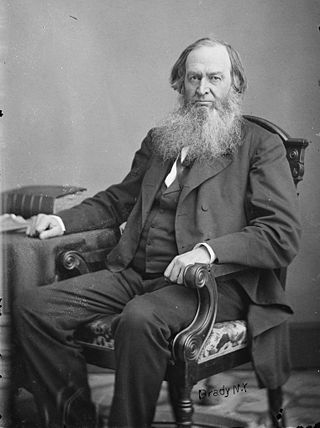

Gerrit Smith, also spelled Gerritt Smith, was an American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidate for President of the United States in 1848, 1856, and 1860. He served a single term in the House of Representatives from 1853 to 1854.

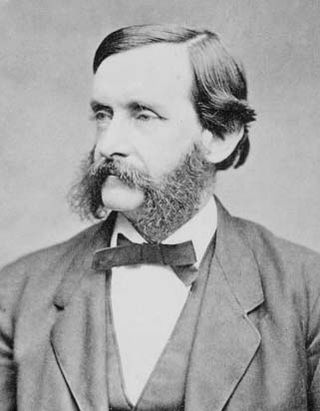

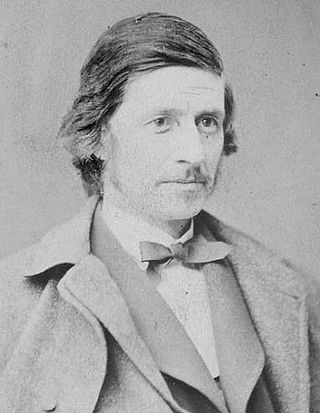

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who went by the name Wentworth, was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in abolitionism in the United States during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with disunion and militant abolitionism. He was a member of the Secret Six who supported John Brown. During the Civil War, he served as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first federally authorized black regiment, from 1862 to 1864. Following the war, he wrote about his experiences with African-American soldiers and devoted much of the rest of his life to fighting for the rights of freed people, women, and other disfranchised peoples. He is also remembered as a mentor to poet Emily Dickinson.

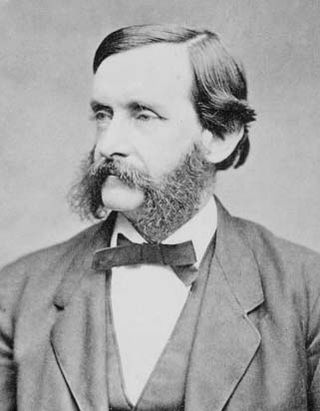

George Luther Stearns was an American industrialist and merchant in Medford, Massachusetts, as well as an abolitionist and a noted recruiter of black soldiers for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Virginia v. John Brown was a criminal trial held in Charles Town, Virginia, in October 1859. The abolitionist John Brown was quickly prosecuted for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection, all part of his raid on the United States federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He was found guilty of all charges, sentenced to death, and was executed by hanging on December 2. He was the first person executed for treason in the United States.

It was in many respects a most remarkable trial. Capital cases have been exceedingly few in the history of our country where trial and conviction have followed so quickly upon the commission of the offense. Within a fortnight from the time when Brown had struck what he believed to be a righteous blow against what he felt to be the greatest sin of the age he was a condemned felon, with only thirty days between his life and the hangman's noose.

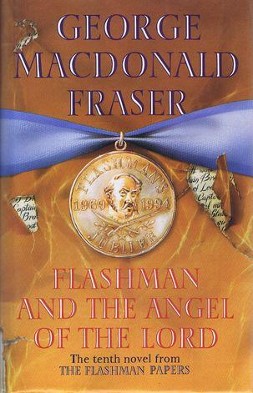

Flashman and the Angel of the Lord is a 1994 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the tenth of the Flashman novels.

Franklin Benjamin Sanborn was an American journalist, teacher, author, reformer, and abolitionist. Sanborn was a social scientist and memorialist of American transcendentalism who wrote early biographies of many of the movement's key figures. He founded the American Social Science Association in 1865 "to treat wisely the great social problems of the day." He was a member of the so-called Secret Six, or "Committee of Six", which funded or helped obtain funding for John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry; in fact, he introduced Brown to the others. A recent scholar describes him as "humorless."

Lewis Sheridan Leary was an African-American harnessmaker from Oberlin, Ohio, who joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, where he was killed.

John Anthony Copeland Jr. was born free in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, free mulattos, who married in Raleigh in 1831. Delilah was born free, while John was manumitted in the will of his master. In 1843 the family moved north, to the abolitionist center of Oberlin, Ohio, where he later attended Oberlin College's preparatory division. He was a highly visible leader in the successful Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, for which he was indicted but not tried. Copeland joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry; other than Brown himself, he was the only member of John Brown's raiders that was at all well known. He was captured, and a marshal from Ohio came to Charles Town to serve him with the indictment. He was indicted a second time, for murder and conspiracy to incite slaves to rebellion. He was found guilty and was hanged on December 16, 1859. There were 1,600 spectators. His family tried but failed to recover his body, which was taken by medical students for dissection, and the bones discarded.

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an abolitionist organization formed in Boston, Massachusetts, to protect escaped slaves from being kidnapped and returned to slavery in the South. The Committee aided hundreds of escapees, most of whom arrived as stowaways on coastal trading vessels and stayed a short time before moving on to Canada or England. Notably, members of the Committee provided legal and other aid to George Latimer, Ellen and William Craft, Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns.

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was an effort by abolitionist John Brown, from October 16 to 18, 1859, to initiate a slave revolt in Southern states by taking over the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. It has been called the dress rehearsal for, or tragic prelude to, the American Civil War.

John Brown Jr. was the eldest son of the abolitionist John Brown. His mother was Brown's first wife, Dianthe Lusk Brown, who died when John Jr. was 11. He was born in Hudson, Ohio. In 1841 he tried teaching in a country school, but left it after one year, finding it frustrating and the children "snotty". In spring 1842 he enrolled at the Grand River Institute in Austinburg, Ohio. In July 1847 he married Wealthy Hotchkiss (1829–1911), who had also studied at the Grand River Institute. The couple settled in Springfield, Massachusetts, and had two children.

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, the abolitionist John Brown led a band of 22 in a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Watson Brown was a son of the abolitionist John Brown and his second wife Mary Day Brown, born in Franklin Mills, Ohio. He was married to Isabell "Belle" Thompson Brown, and they had a son Frederick W., who died of diphtheria at age 4, and is buried at what is now the John Brown Farm State Historic Site in North Elba, New York.

Francis Jackson Meriam was an American abolitionist, born on November 17, 1837, in Framingham, Massachusetts, and died on November 28, 1865, in New York City. He was named for his grandfather, Francis Jackson, who had been president of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Hinton describes him as "handsome, well-to-do, cultivated, and traveled". Instead of college, he lived in Paris for some time. In contrast, Sanborn described him as "enthusiastic and resolute, but with little judgment, and in feeble health; altogether, one would say, a very unfit person to take part actively in Brown’s enterprise." He was blind in one eye. He was the only one of John Brown's raiders who helped him financially.

George Sennott was an American lawyer and abolitionist. He was the legal defense for two of the John Brown's raiders in 1859. In his lifetime, Sennott was considered one of the best known lawyers in Boston, according to The Boston Post newspaper.