Loa or lwa are the spirits of Haitian Vodou and Louisiana Voodoo. They are intermediaries between Bondye – the Supreme Creator, but who is distant from the world – and humanity. Loa are not deities in and of themselves. Unlike saints or angels, however, they are not simply prayed to; they are served. They are each distinct beings with their own personal likes and dislikes, distinct sacred rhythms, songs, dances, ritual symbols (veves), and special modes of service.

Vodun is practiced by the Aja, Ewe, and Fon peoples of Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Agassou is a loa who guards the old traditions of Dahomey in the West African Vodun religion and the rada loa of Haitian Vodou.

Ayizan is the loa of the marketplace and commerce in Vodou, especially in Haiti.

L'inglesou is a Vodou loa who lives in the wild areas of Haiti and kills anyone who offends him.

Haitian Vodou is a syncretic mixture of Roman Catholic rituals developed during the French colonial period, based on traditional African beliefs, with roots in Dahomey, Kongo and Yoruba traditions, and folkloric influence from the indigenous Taino peoples of Haiti. The Loa, or spirits with whom Vodouisants work and practice, are not gods but servants of the Supreme Creator Bondye. In keeping with the French-Catholic influence of the faith, vodousaints are for the most part monotheists, believing that the Loa are great and powerful forces in the world with whom humans interact and vice versa, resulting in a symbiotic relationship intended to bring both humans and the Loa back to Bondye. "Vodou is a religious practice, a faith that points toward an intimate knowledge of God, and offers its practitioners a means to come into communion with the Divine, through an ever evolving paradigm of dance, song and prayers."

Dutty Boukman was an early leader of the Haitian Revolution. Born in Senegambia, he was captured, enslaved and transported to Jamaica. He eventually ended up in Haiti, where he became a leader of the Maroons and a vodou houngan (priest).

Loco is a loa, patron of healers and plants, especially trees in the Vodou religion. He is a racine (root) and a rada loa. Among several other loa, he is linked with the poteau mitan or center post in a Vodou peristyle.

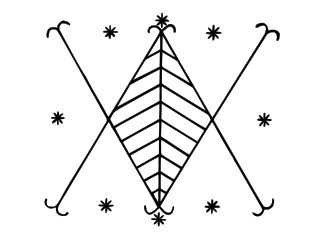

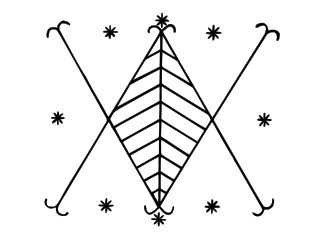

A veve is a religious symbol commonly used in different branches of Vodun throughout the African diaspora, such as Haitian Vodou. Veves should not be confused with the patipembas used in Palo, nor the pontos riscados used in Umbanda and Quimbanda since these are separate African religions. The veve acts as a "beacon" for the loa, and will serve as a loa's representation during rituals.

Bois Caïman was the site of the first major meeting of enslaved Blacks during which the first major slave insurrection of the Haitian Revolution was planned.

Homosexuality in Haitian Vodou is religiously acceptable and homosexuals are allowed to participate in all religious activities. However, in countries with large Vodou populations, some Christian influence may have given homosexuality a social stigma, at least on some levels of society.

A mambo is a priestess in the Haitian Vodou religion. Haitian Vodou's conceptions of priesthood stem from the religious traditions of enslaved people from Dahomey, in what is today Benin. For instance, the term mambo derives from the Fon word nanbo. Like their West African counterparts, Haitian mambos are female leaders in Vodou temples who perform healing work and guide others during complex rituals. This form of female leadership is prevalent in urban centers such as Port-au-Prince. Typically, there is no hierarchy among mambos and houngans. These priestesses and priests serve as the heads of autonomous religious groups and exert their authority over the devotees or spiritual servants in their hounfo (temples).

The Rada are a family of lwa spirits in the religion of Haitian Vodou. They are regarded as being sweet-tempered and "cool", in this contrasting with the Petro lwa, which are regarded as volatile and "hot".

Haitian Vodou is an African diasporic religion that gradually developed in Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional religions of West Africa and the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. Adherents are known as Vodouists or "servants of the spirits". There is no central authority in control of Vodou, which is organised through autonomous groups.

Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo or Creole Voodoo, is an African diasporic religion originating in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional religions of West Africa, the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, and Haitian Vodou. The religion existed from the 18th century through to the early 20th, at which point it had effectively died out, only to be revived in an altered form in the late 20th century. There is no central authority in control of Louisiana Voodoo, which is organised through autonomous groups.

Vodou drumming and associated ceremonies are folk ritual faith system of henotheistic religion of Haitian Vodou originated and inextricable part of Haitian culture.

A hounfour is a Vodou temple. The leader of the ceremony is a male priest called a houngan, or a female priest called a mambo. The term is believed to derive from the Fon houn for, "abode of spirits."

Christian-Vodou relations have been marked by syncretism and conflicts, especially in Haiti, but less so in Louisiana and elsewhere.

Cuban Vodú is a religion indigenous to Cuba. It is a religion formed from the blending of Fon and Ewe beliefs and Dahomey religion which came to form Haitian Vodou. Loa are worshiped by the religion's practitioners. Cuban Vodú is noteworthy for its popularity in the Oriente Province of Cuba and a lack of academic study of the religion.

Haitian Vodou art is art related to the Haitian Vodou religion. This religion has its roots in West African traditional religions brought to Haiti by slaves, but has assimilated elements from Europe and the Americas and continues to evolve. The most distinctive Vodou art form is the drapo Vodou, an embroidered flag often decorated with sequins or beads, but the term covers a wide range of visual art forms including paintings, embroidered clothing, clay or wooden figures, musical instruments and assemblages. Since the 1950s there has been growing demand for Vodou art by tourists and collectors.