In linguistics and etymology, suppletion is traditionally understood as the use of one word as the inflected form of another word when the two words are not cognate. For those learning a language, suppletive forms will be seen as "irregular" or even "highly irregular".

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut is a system of apophony in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

The laryngeal theory is a theory in historical linguistics positing that the Proto-Indo-European language included a number of laryngeal consonants that are not reconstructable by direct application of the comparative method to the Indo-European family. The "missing" sounds remain consonants of an indeterminate place of articulation towards the back of the mouth, though further information is difficult to derive. Proponents aim to use the theory to:

In Indo-European studies, a thematic vowel or theme vowel is the vowel *e or *o from ablaut placed before the ending of a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word. Nouns, adjectives, and verbs in the Indo-European languages with this vowel are thematic, and those without it are athematic. Used more generally, a thematic vowel is any vowel found at the end of the stem of a word.

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages.

In phonetics and phonology, gemination, or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from stress. Gemination is represented in many writing systems by a doubled letter and is often perceived as a doubling of the consonant. Some phonological theories use 'doubling' as a synonym for gemination, while others describe two distinct phenomena.

The Germanic language family is one of the language groups that resulted from the breakup of Proto-Indo-European (PIE). It in turn divided into North, West and East Germanic groups, and ultimately produced a large group of mediaeval and modern languages, most importantly: Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish (North); English, Dutch and German (West); and Gothic.

Proto-Indo-European verbs reflect a complex system of morphology, more complicated than the substantive, with verbs categorized according to their aspect, using multiple grammatical moods and voices, and being conjugated according to person, number and tense. In addition to finite forms thus formed, non-finite forms such as participles are also extensively used.

A feature common to all Indo-European languages is the presence of a verb corresponding to the English verb to be.

In historical linguistics, the German term grammatischer Wechsel refers to the effects of Verner's law when they are viewed synchronically within the paradigm of a Germanic verb.

The Germanic spirant law, or Primärberührung, is a specific historical instance in linguistics of dissimilation that occurred as part of an exception of Grimm's law in Proto-Germanic, the ancestor of Germanic languages.

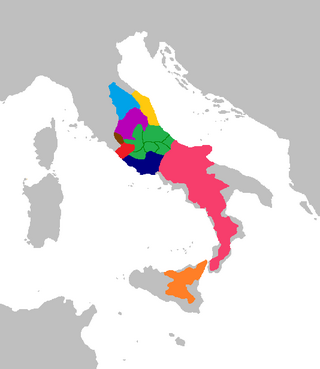

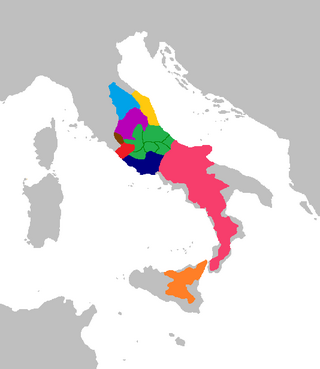

Latin is a member of the broad family of Italic languages. Its alphabet, the Latin alphabet, emerged from the Old Italic alphabets, which in turn were derived from the Etruscan, Greek and Phoenician scripts. Historical Latin came from the prehistoric language of the Latium region, specifically around the River Tiber, where Roman civilization first developed. How and when Latin came to be spoken has long been debated.

Sievers's law in Indo-European linguistics accounts for the pronunciation of a consonant cluster with a glide before a vowel as it was affected by the phonetics of the preceding syllable. Specifically, it refers to the alternation between *iy and *y, and possibly *uw and *w as conditioned by the weight of the preceding syllable. For instance, Proto-Indo-European (PIE) *kor-yo-s became Proto-Germanic *harjaz, Gothic harjis "army", but PIE *ḱerdh-yo-s became Proto-Germanic *hirdijaz, Gothic hairdeis "shepherd". It differs from ablaut in that the alternation has no morphological relevance but is phonologically context-sensitive: PIE *iy followed a heavy syllable, but *y would follow a light syllable.

Proto-Indo-European nominals include nouns, adjectives, and pronouns. Their grammatical forms and meanings have been reconstructed by modern linguists, based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. This article discusses nouns and adjectives; Proto-Indo-European pronouns are treated elsewhere.

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology.

The roots of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) are basic parts of words to carry a lexical meaning, so-called morphemes. PIE roots usually have verbal meaning like "to eat" or "to run". Roots never occurred alone in the language. Complete inflected verbs, nouns, and adjectives were formed by adding further morphemes to a root and potentially changing the root's vowel in a process called ablaut.

Kluge's law is a controversial Proto-Germanic sound law formulated by Friedrich Kluge. It purports to explain the origin of the Proto-Germanic long consonants *kk, *tt, and *pp as originating in the assimilation of *n to a preceding voiced plosive consonant, under the condition that the *n was part of a suffix which was stressed in the ancestral Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The name "Kluge's law" was coined by Kauffmann (1887) and revived by Frederik Kortlandt (1991). As of 2006, this law has not been generally accepted by historical linguists.

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. Proto-Italic descended from the earlier Proto-Indo-European language.

Historical linguistics has made tentative postulations about and multiple varyingly different reconstructions of Proto-Germanic grammar, as inherited from Proto-Indo-European grammar. All reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk (*).