Cyrus Roberts Vance was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary of Defense in the Johnson administration. During the Kennedy administration he was Secretary of the Army and General Counsel of the Department of Defense.

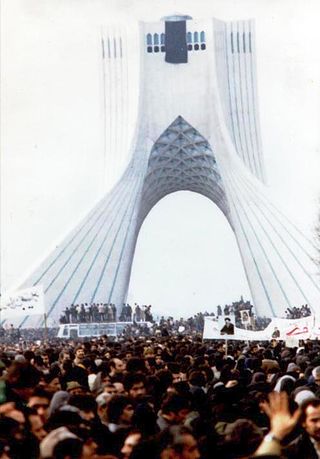

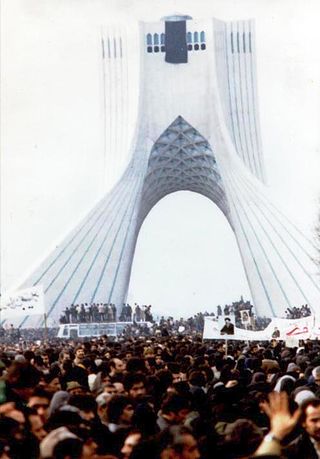

Fifty-three United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage in Iran from November 4, 1979 to their release on January 20, 1981. They were taken as hostages by a group of armed Iranian college students who supported the Iranian Revolution, including Hossein Dehghan, Mohammad Ali Jafari and Mohammad Bagheri. The students took over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The crisis is considered a pivotal episode in the history of Iran–United States relations.

Operation Eagle Claw was a failed operation by the United States Armed Forces ordered by U.S. President Jimmy Carter to attempt the rescue of 53 embassy staff held captive at the Embassy of the United States, Tehran, on 24 April 1980. The operation, one of Delta Force's first, encountered many obstacles and failures and was subsequently aborted. Eight helicopters were sent to the first staging area called Desert One, but only five arrived in operational condition. One had encountered hydraulic problems, another was caught in a sand storm, and the third showed signs of a cracked rotor blade. During the operational planning, it was decided that the mission would be aborted if fewer than six helicopters remained operational upon arrival at the Desert One site, despite only four being absolutely necessary. In a move that is still discussed in military circles, the field commanders advised President Carter to abort the mission, which he did.

Sadegh Ghotbzadeh was an Iranian politician who served as a close aide of Ayatollah Khomeini during his 1978 exile in France and was foreign minister during the Iran hostage crisis following the Iranian Revolution. In 1982, he was executed for allegedly plotting the assassination of Ayatollah Khomeini and the overthrow of the Islamic Republic.

The Iran–United States Claims Tribunal (IUSCT) is an international arbitral tribunal established under the Algiers Accords, an agreement between the United States and Iran mediated by Algeria and formalized through two declarations issued on January 19, 1981. The tribunal was created to address disputes between the two countries stemming from the 1979–1981 Iran hostage crisis and related incidents involving U.S. embassy staff in Tehran.

United States of America v. Islamic Republic of Iran [1980] ICJ 1 is a public international law case brought to the International Court of Justice by the United States of America against Iran in response to the Iran hostage crisis, where United States diplomatic offices and personnel were seized by militant revolutionaries.

The "Canadian Caper" was the joint covert rescue by the Canadian government and the CIA of six American diplomats who had evaded capture during the seizure of the United States embassy in Tehran, Iran, on November 4, 1979, after the Iranian Revolution, when Islamist students took most of the American embassy personnel hostage, demanding the return of the US-backed Shah for trial.

The Algiers Accords of January 19, 1981 was a set of obligations and commitments undertaken independently by the United States and Iran to resolve the Iran hostage crisis, brokered by the Algerian government and signed in Algiers on January 19, 1981. The crisis began from the takeover of the American embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, where Iranian students took hostage of present American embassy staff. By this accord and its adherence, 52 American citizens were able to leave Iran. With the two countries unable to settle on mutually agreeable terms, particularly for quantitative financial obligations, Algerian mediators proposed an alternative agreement model - one where each country undertook obligations under the accords independently, rather than requiring both countries to mutually adhere to the same terms under a bilateral agreement.

This article is a timeline of events relevant to the Islamic Revolution in Iran. For earlier events refer to Pahlavi dynasty and for later ones refer to History of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This article doesn't include the reasons of the events and further information is available in Islamic revolution of Iran.

In July 2001, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika became the first Algerian President to visit the White House since 1985. This visit, followed by a second meeting in November 2001, and President Bouteflika's participation at the June 2004 G8 Sea Island Summit, is indicative of the growing relationship between the United States and Algeria. Since the September 11 attacks in the United States, contacts in key areas of mutual concern, including law enforcement and counter-terrorism cooperation, have intensified. Algeria publicly condemned the terrorist attacks on the United States and has been strongly supportive of the Global War on Terrorism. The United States and Algeria consult closely on key international and regional issues. The pace and scope of senior-level visits has accelerated.

The Embassy of the United States of America in Tehran was the American diplomatic mission in the Imperial State of Iran. Direct bilateral diplomatic relations between the two governments were severed following the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and the subsequent seizure of the embassy in November 1979.

The Cuba–United States Maritime Boundary Agreement is a 1977 treaty between Cuba and the United States that set the international maritime boundary between the two states. Maritime boundary delimitation was necessary to facilitate law enforcement and resource management, and to avoid conflict, within the countries' overlapping two-hundred mile maritime zones.

Richard Henry Morefield was an American diplomat who served in the United States Foreign Service. He was one of the 66 staff members at the American embassy in Tehran who were taken captive by a militant Islamist student group called the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line on November 4, 1979, in what became known as the Iran hostage crisis. He was one of 52 Americans who were held as a hostage for 444 days, until negotiations for the remaining captives being held hostage were concluded with the signing of the Algiers Accords on January 19, 1981, with their release coming the following day.

Public Law 113-110 is a law that "ban(s) Iran's new United Nations ambassador, who has ties to a terrorist group, from entering the United States." Iran's proposed ambassador, Hamid Aboutalebi, is controversial due to his involvement in the Iran hostage crisis, in which a number of American diplomats from the US embassy in Tehran were held captive from 1979 until 1981. Aboutalebi said he did not participate in the takeover of the US embassy, but was brought in to translate and negotiate following the occupation. President Barack Obama told Iran that Aboutalebis selection was not "viable" and Congress reacted by passing this law to ban his presence in the United States.

Roberts Bishop "Bob" Owen was an American lawyer and diplomat. He served as Legal Adviser of the Department of State from 1979 to 1981 and acted as a mediator and arbitrator in several international disputes.

This is a timeline of the Iran hostage crisis (1979–1981), starting from the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi's leaving of Iran and ending at the return of all hostages to the United States.

In 2016, the BBC published a report which stated that the administration of United States President Jimmy Carter (1977–1981) had extensive contact with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his entourage in the prelude to the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The report was based on "newly declassified US diplomatic cables". According to the report, as mentioned by The Guardian, Khomeini "went to great lengths to ensure the Americans would not jeopardise his plans to return to Iran - and even personally wrote to US officials" and assured them not to worry about their interests in Iran, particularly oil. According to the report, in turn, Carter and his administration helped Khomeini and made sure that the Imperial Iranian army would not launch a military coup.

Seghir Mostefai was an Algerian lawyer, economist and high civil servant. He graduated with a master's degree in law and economics from Sorbonne University, Paris. Long time anti-colonial activist with responsibilities in the political independentist organization in Algeria and later in exile in Tunis, he participated to the negotiation of the Évian Accords leading to the independence of Algeria. He founded the Central Bank of Algeria, created the national currency and served as Governor of the Central Bank, representing Algeria at the board of the IMF for 20 years.

The Villa Montfeld is an historic residence in the El Biar district of Algiers, Algeria, which serves as the residence of the Ambassador of the United States to Algeria. The villa was built in the mid-19th century and was reconstructed in a Moorish Revival style by the English architect Benjamin Bucknall between 1878 and 1895. In 1947 the villa was bought by the United States government for use as an ambassadorial residence. In 1981 Villa Montfeld hosted negotiations leading to the Algiers Accords, which ended the Iran hostage crisis.

The Role of Algeria in the Resolution of the American Hostages Crisis