Related Research Articles

Nergal was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations indicating that his cult survived into the period of Achaemenid domination. He was primarily associated with war, death, and disease, and has been described as the "god of inflicted death". He reigned over Kur, the Mesopotamian underworld, depending on the myth either on behalf of his parents Enlil and Ninlil, or in later periods as a result of his marriage with the goddess Ereshkigal. Originally either Mammitum, a goddess possibly connected to frost, or Laṣ, sometimes assumed to be a minor medicine goddess, were regarded as his wife, though other traditions existed, too.

Nammu was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as a creator deity in the local theology of Eridu. It is assumed that she was associated with water. She is also well attested in connection with incantations and apotropaic magic. She was regarded as the mother of Enki, and in a single inscription she appears as the wife of Anu, but it is assumed that she usually was not believed to have a spouse. From the Old Babylonian period onwards, she was considered to be the mother of An (Heaven) and Ki (Earth), as well as a representation of the primeval sea/ocean, an association that may have come from influence from the goddess Tiamat.

Zababa was the tutelary deity of the city of Kish in ancient Mesopotamia. He was a war god. While he was regarded as similar to Ninurta and Nergal, he was never fully conflated with them. His worship is attested from between the Early Dynastic to the Achaemenid periods, with the Old Babylonian kings being particularly devoted to him. Starting with the Old Babylonian period, he was regarded as married to the goddess Bau.

Ninkasi was the Mesopotamian goddess of beer and brewing. It is possible that in the first millennium BC she was known under the variant name Kurunnītu, derived from a term referring to a type of high quality beer. She was associated with both positive and negative consequences of the consumption of beer. In god lists, such as the An = Anum list and the Weidner god list, she usually appears among the courtiers of the god Enlil, alongside deities such as Ninimma and Ninmada. She could also be paired with Siraš, a goddess of similar character, who sometimes was regarded as her sister. A possible association between her and the underworld deities Nungal and Laṣ is also attested, possibly in reference to the possible negative effects of alcohol consumption.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian deity of vegetation, the underworld and sometimes war. He was commonly associated with snakes. Like Dumuzi, he was believed to spend a part of the year in the land of the dead. He also shared many of his functions with his father Ninazu.

Nirah was a Mesopotamian god who served as the messenger (šipru) of Ištaran, the god of Der. He was depicted in the form of a snake.

Ninazu was a Mesopotamian god of the underworld of Sumerian origin. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. He was frequently associated with Ereshkigal, either as a son, husband, or simply as a deity belonging to the same category of underworld gods.

Enmesharra was a Mesopotamian god associated with the underworld. He was regarded as a member of an inactive old generation of deities, and as such was commonly described as a ghost or resident of the underworld. He is best known from various lists of primordial deities, such as the so-called "theogony of Enlil," which lists many generations of ancestral deities.

Isimud was a Mesopotamian god regarded as the divine attendant (sukkal) of the god Enki (Ea). He was depicted with two faces. No references to temples dedicated to him are known, though ritual texts indicate he was worshiped in Uruk and Babylon. He was also incorporated into Hurrian religion and Hittite religion. In myths, he appears in his traditional role as a servant of Enki.

Šumugan, Šamagan, Šumuqan or Šakkan (𒀭𒄊) was a god worshipped in Mesopotamia and ancient Syria. He was associated with animals.

Tishpak (Tišpak) was a Mesopotamian god associated with the ancient city Eshnunna and its sphere of influence, located in the Diyala area of Iraq. He was primarily a war deity, but he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mushussu and bashmu, and with kingship.

Nuska or Nusku, possibly also known as Našuḫ, was a Mesopotamian god best attested as the sukkal of Enlil. He was also associated with fire and light, and could be invoked as a protective deity against various demons, such as Lamashtu or gallu. His symbols included a staff, a lamp and a rooster. Various traditions existed regarding his genealogy, with some of them restricted to texts from specific cities. His wife was the goddess Sadarnunna, whose character is poorly known. He could be associated with the fire god Gibil, as well as with various courtiers of Enlil, such as Shuzianna and Ninimma.

Lugal-irra (𒀭𒈗𒄊𒊏) and Meslamta-ea (𒀭𒈩𒇴𒋫𒌓𒁺𒀀) were a pair of Mesopotamian gods who typically appear together in cuneiform texts and were described as the "divine twins" (Maštabba). There were regarded as warrior gods and as protectors of doors, possibly due to their role as the gatekeepers of the underworld. In Mesopotamian astronomy they came to be associated with a pair of stars known as the "Great Twins", Alpha Geminorum and Beta Geminorum. They were both closely associated with Nergal, and could be either regarded as members of his court or equated with him. Their cult centers were Kisiga and Dūrum. While no major sanctuaries dedicated to them are attested elsewhere, they were nonetheless worshiped in multiple other cities.

Sukkal was a term which could denote both a type of official and a class of deities in ancient Mesopotamia. The historical sukkals were responsible for overseeing the execution of various commands of the kings and acted as diplomatic envoys and translators for foreign dignitaries. The deities referred to as sukkals fulfilled a similar role in mythology, acting as servants, advisors and envoys of the main gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon, such as Enlil or Inanna. The best known sukkal is the goddess Ninshubur. In art, they were depicted carrying staves, most likely understood as their attribute. They could function as intercessory deities, believed to mediate between worshipers and the major gods.

Alammuš (Alammush) was a Mesopotamian god. He was the sukkal of the moon god Nanna, and like him was worshiped in Ur. He was also closely associated with the cattle god Ningublaga, and especially in astronomical texts they could be regarded as twin brothers.

Idlurugu or Id (dÍD) was a Mesopotamian god regarded as both a river deity and a divine judge. He was the personification of a type of trial by ordeal, which shared its name with him.

Laṣ was a Mesopotamian goddess who was commonly regarded as the wife of Nergal, a god associated with war and the underworld. Instances of both conflation and coexistence of her and another goddess this position was attributed to, Mammitum, are attested in a number sources. Her cult centers were Kutha in Babylonia and Tarbiṣu in Assyria.

Alla or Alla-gula was a Mesopotamian god associated with the underworld. He functioned as the sukkal of Ningishzida, and most likely was a dying god similar to Dumuzi and Damu, but his character is not well known otherwise. He had his own cult center, Esagi, but its location is presently unknown.

Ebiḫ (Ebih) was a Mesopotamian god presumed to represent the Hamrin Mountains. It has been suggested that while such an approach was not the norm in Mesopotamian religion, no difference existed between the deity and the associated location in his case. It is possible that he was depicted either in a non-anthropomorphic or only partially anthropomorphic form. He appears in theophoric names from the Diyala area, Nuzi and Mari from between the Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian periods, and in later Middle Assyrian ones from Assyria. He was also actively venerated in Assur in the Neo-Assyrian period, and appears in a number of royal Tākultu rituals both as a mountain and as a personified deity.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiggermann 1998, p. 570.

- 1 2 3 4 Woods 2004, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiggermann 1998, p. 571.

- 1 2 3 Beaulieu 2021, p. 171.

- 1 2 Lambert 2013, p. 238.

- ↑ Stol 2014, p. 65.

- ↑ Koppen & Lacambre 2020, p. 153.

- ↑ Woods 2004, p. 73.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1998, pp. 571–572.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 244.

- 1 2 Lambert 2013, p. 270.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ Woods 2004, p. 77.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2021, p. 170.

- ↑ Michalowski 2008, p. 133.

- 1 2 Lambert 1999, p. 153.

- ↑ Lambert 1999, p. 155.

- ↑ Lambert 1999, p. 154.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 54.

- 1 2 Peterson 2009, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 Wiggermann 1998, p. 574.

- ↑ McEwan 1983, p. 226.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 239.

- ↑ McEwan 1983, p. 225.

- ↑ Peterson 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ McEwan 1983, p. 228.

Bibliography

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2021). "Remarks on Theophoric Names in the Late Babylonian Archives from Ur". Individuals and Institutions in the Ancient Near East. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9781501514661-006.

- Koppen, Frans van; Lacambre, Denis (2020). "Sippar and the Frontier between Ešnunna and Babylon. New Sources for the History of Ešnunna in the Old Babylonian Period". Jaarbericht van Het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux. 41. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1999). "Literary Texts from Nimrud". Archiv für Orientforschung. 46/47. Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO)/Institut für Orientalistik: 149–155. ISSN 0066-6440. JSTOR 41668445 . Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2013). Babylonian creation myths. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-861-9. OCLC 861537250.

- McEwan, Gilbert J. P. (1983). "dMUŠ and Related Matters". Orientalia. 52 (2). GBPress - Gregorian Biblical Press: 215–229. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43077512 . Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2008), "Puzur-Niraḫ", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-04

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2009). "A Sumerian Literary Fragment Involving the God Irḫan" (PDF). Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires (NABU) (3).

- Stol, Marten (2014), "Tišpak", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-04

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1997). "Transtigridian Snake Gods". In Finkel, I. L.; Geller, M. J. (eds.). Sumerian Gods and their Representations. ISBN 978-90-56-93005-9.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998), "Niraḫ, Irḫan", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-04

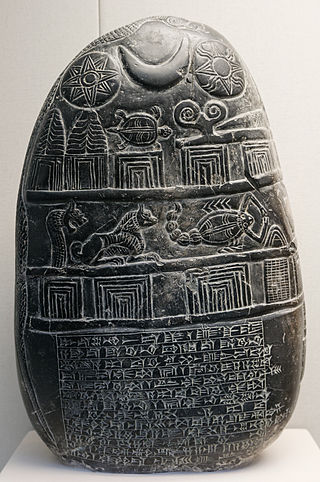

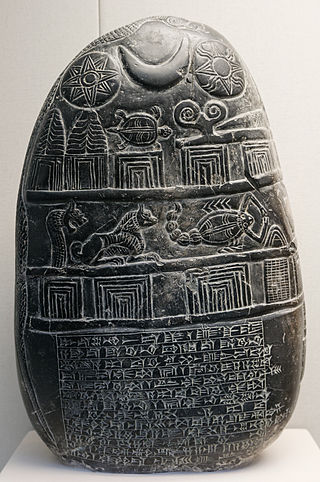

- Woods, Christopher E. (2004). "The Sun-God Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina Revisited". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 56. American Schools of Oriental Research: 23–103. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 3515920 . Retrieved 2022-05-04.