Democritus was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. Democritus wrote extensively on a wide variety of topics.

Empedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the four classical elements. He also proposed forces he called Love and Strife which would mix and separate the elements, respectively.

Heraclitus was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on ancient and modern Western philosophy, including through the works of Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, and Heidegger.

Leucippus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He is traditionally credited as the founder of atomism, which he developed with his student Democritus. Leucippus divided the world into two entities: atoms, indivisible particles that make up all things, and the void, the nothingness that exists between the atoms. He developed his philosophy as a response to the Eleatics, who believed that all things are one and the void does not exist. Leucippus's ideas were influential in ancient and Renaissance philosophy. Leucippus was the first Western philosopher to develop the concept of atoms, but his ideas only bear a superficial resemblance to modern atomic theory.

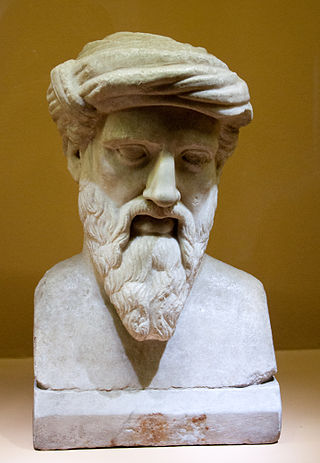

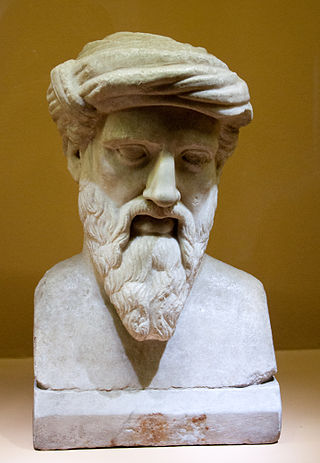

Pythagoras of Samos was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and, through them, the West in general. Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend; modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton in southern Italy, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle.

Parmenides of Elea was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as Early Greek Philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of these early philosophers spanned the workings of the natural world as well as human society, ethics, and religion. They sought explanations based on natural law rather than the actions of gods. Their work and writing has been almost entirely lost. Knowledge of their views comes from testimonia, i.e. later authors' discussions of the work of pre-Socratics. Philosophy found fertile ground in the ancient Greek world because of the close ties with neighboring civilizations and the rise of autonomous civil entities, poleis.

Zeno of Elea was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He was a student of Parmenides and one of the Eleatics. Born in Elea, Zeno defended his instructor's belief in monism, the idea that only one single entity exists that makes up all of reality. He rejected the existence of space, time, and motion. To disprove these concepts, he developed a series of paradoxes to demonstrate why these are impossible. Though his original writings are lost, subsequent descriptions by Plato, Aristotle, Diogenes Laertius, and Simplicius of Cilicia have allowed study of his ideas.

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and later evolved into Roman philosophy.

Diogenes of Apollonia was an ancient Greek philosopher, and was a native of the Milesian colony Apollonia in Thrace. He lived for some time in Athens. He believed air to be the one source of all being from which all other substances were derived, and, as a primal force, to be both divine and intelligent. He also wrote a description of the organization of blood vessels in the human body. His ideas were parodied by the dramatist Aristophanes, and may have influenced the Orphic philosophical commentary preserved in the Derveni papyrus. His philosophical work has not survived in a complete form, and his doctrines are known chiefly from lengthy quotations of his work by Simplicius, as well as a few summaries in the works of Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Aetius.

Xenophanes of Colophon was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer from Ionia who travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early Classical Antiquity.

Philolaus was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and the most outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras developed a school of philosophy that was dominated by both mathematics and mysticism. Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views. He may have been the first to write about Pythagorean doctrine. According to August Böckh (1819), who cites Nicomachus, Philolaus was the successor of Pythagoras.

Melissus of Samos was the third and last member of the ancient school of Eleatic philosophy, whose other members included Zeno and Parmenides. Little is known about his life, except that he was the commander of the Samian fleet in the Samian War. Melissus’ contribution to philosophy was a treatise of systematic arguments supporting Eleatic philosophy. Like Parmenides, he argued that reality is ungenerated, indestructible, indivisible, changeless, and motionless. In addition, he sought to show that reality is wholly unlimited, and infinitely extended in all directions; and since existence is unlimited, it must also be one.

The Eleatics were a group of pre-Socratic philosophers and school of thought in the 5th century BC centered around the ancient Greek colony of Elea, located around 80 miles south-east of Naples in southern Italy, then known as Magna Graecia.

Hippasus of Metapontum was a Greek philosopher and early follower of Pythagoras. Little is known about his life or his beliefs, but he is sometimes credited with the discovery of the existence of irrational numbers. The discovery of irrational numbers is said to have been shocking to the Pythagoreans, and Hippasus is supposed to have drowned at sea, apparently as a punishment from the gods for divulging this and crediting it to himself instead of Pythagoras which was the norm in Pythagorean society. However, the few ancient sources who describe this story either do not mention Hippasus by name or alternatively tell that Hippasus drowned because he revealed how to construct a dodecahedron inside a sphere. The discovery of irrationality is not specifically ascribed to Hippasus by any ancient writer.

The Megarian school of philosophy, which flourished in the 4th century BC, was founded by Euclides of Megara, one of the pupils of Socrates. Its ethical teachings were derived from Socrates, recognizing a single good, which was apparently combined with the Eleatic doctrine of Unity. Some of Euclides' successors developed logic to such an extent that they became a separate school, known as the Dialectical school. Their work on modal logic, logical conditionals, and propositional logic played an important role in the development of logic in antiquity.

Hermotimus of Clazomenae, was a possibly historic or legendary Presocratic philosopher about whom many legendary feats were ascribed in antiquity, including the ability for his soul to leave his body and travel around. Some ancient sources also considered him a previous reincarnation of Pythagoras. Aristotle also credited him with some of the metaphysical doctrines on Nous that were more commonly attributed to Anaxagoras.

This page is a list of topics in ancient philosophy.

David Neil Sedley FBA is a British philosopher and historian of philosophy. He was the seventh Laurence Professor of Ancient Philosophy at Cambridge University.

John Earle Raven was an English classical scholar, notable for his work on pre-Socratic philosophy, and amateur botanist.