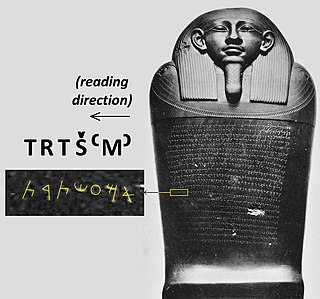

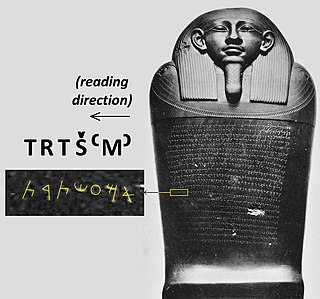

The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

Jean-Jacques Barthélemy was a French Catholic clergyman, archaeologist, numismatologist and scholar who became the first person to decipher an extinct language. He deciphered the Palmyrene alphabet in 1754 and the Phoenician alphabet in 1758.

The Temple of Eshmun is an ancient place of worship dedicated to Eshmun, the Phoenician god of healing. It is located near the Awali river, 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Sidon in southwestern Lebanon. The site was occupied from the 7th century BC to the 8th century AD, suggesting an integrated relationship with the nearby city of Sidon. Although originally constructed by Sidonian king Eshmunazar II in the Achaemenid era to celebrate the city's recovered wealth and stature, the temple complex was greatly expanded by Bodashtart, Yatonmilk and later monarchs. Because the continued expansion spanned many centuries of alternating independence and foreign hegemony, the sanctuary features a wealth of different architectural and decorative styles and influences.

Edward Lipiński, or Edouard Lipiński, was a Polish-Belgian Biblical scholar and Orientalist, professor and exegete at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Eshmunazar II was the Phoenician king of Sidon. He was the grandson of Eshmunazar I, and a vassal king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar II succeeded his father Tabnit I who ruled for a short time and died before the birth of his son. Tabnit I was succeeded by his sister-wife Amoashtart who ruled alone until Eshmunazar II's birth, and then acted as his regent until the time he would have reached majority. Eshmunazar II died prematurely at the age of 14. He was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.

Bodashtart was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon, the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

Gaby Emile Layoun was the Lebanese Minister of Culture, announced as part of the cabinet led by Najib Mikati. He represents the Free Patriotic Movement. Layoun is married and has two children. He holds a diploma in engineering, a Lebanese Baccalaureate in mathematics (1982) and a Sacred Heart of the city of Zahle.

The Phoenician port of Beirut, also known as the Phoenician Harbour of Beirut and archaeological site BEY039 is located between Rue Allenby and Rue Foch in Beirut, Lebanon. Studies have shown that the Bronze Age waterfront lay around 300 metres (330 yd) behind the modern port due to coastal regularisation and siltation. It was excavated and reported on by Josette Elayi and Hala Sayegh in 2000 and determined to date to the Iron Age III and Persian periods. Two nineteenth-century Ottoman docks were also unearthed during construction, just to the north of this area at archaeological sites BEY018 and BEY019.

Phoenico-Persian Quarter is located in Beirut, Lebanon.

Abdashtart I was a king of the Phoenician city-state of Sidon who reigned from 365 BC to 352 BC following the death of his father, Baalshillem II.

Yatonmilk was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and a vassal to the Achaemenid king of kings Darius I.

The Baalshillem Temple Boy, or Ba'al Sillem Temple Boy, is a votive statue of a "temple boy" with a Phoenician inscription known as KAI 281. It was found along with a number of other votive statues of children near the canal in the Temple of Eshmun in 1963-64 by Maurice Dunand, and is currently in the National Museum of Beirut.

Eshmunazar I was a priest of Astarte and the Phoenician King of Sidon. He was the founder of his namesake dynasty, and a vassal king of the Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar participated in the Neo-Babylonian campaigns against Egypt under the command of either Nebuchadnezzar II or Nabonidus. The Sidonian king is mentioned in the funerary inscriptions engraved on the royal sarcophagi of his son Tabnit I and his grandson Eshmunazar II. The monarch's name is also attested in the dedicatory temple inscriptions of his other grandson, King Bodashtart.

Baalshillem I was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He was succeeded by his son Abdamon to the throne of Sidon.

Baalshillem II was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and the great-grandson of Baalshillem I who founded the namesake dynasty. He succeeded Baana to the throne of Sidon, and was succeeded by his son Abdashtart I. The name Baalshillem means "recompense of Baal" in Phoenician.

The Arwad bilingual, also the Arados inscription, is a Phoenician-Greek inscription from Arwad, Syria.

Amoashtart was a Phoenician queen of Sidon during the Persian period. She was the daughter of Eshmunazar I, and the wife of her brother, Tabnit. When Tabnit died, Amoashtart became co-regent to her then-infant son, Eshmunazar II, but after the boy died "in his fourteenth year", she was succeeded by her nephew Bodashtart, possibly in a palace coup. Modern historians have characterized her as an "energetic, responsible [woman], and endowed with immense political acumen, [who] exercised royal functions for many years".

Abdamon (also transliterated Abdamun ; Phoenician: 𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤌𐤍, was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He was succeeded by his son Baana to the throne of Sidon.

The Phoenician sanctuary of Kharayeb is a historic temple in the hinterland of Tyre, Southern Lebanon, that was excavated in three stages. In 1946, Maurice Chehab, head of Lebanon's Directorate General of Antiquities, led the first mission that revealed a Hellenistic period temple and thousands of clay figurines dating from the sixth-to-first centuries BC. Excavations in 1969 by Lebanese archaeologist Brahim Kaoukabani and in 2009 by the Government of Italy yielded evidence of cultic practices, and produced a detailed reconstruction of the sanctuary's architecture.

Al-Kharayeb is a historic municipality in the Sidon District in the South Governorate, Lebanon. The town is 77 km (48 mi) south of Beirut, and stands at an average altitude of 190 m (620 ft) above sea level. The town boasts a rich historical legacy, with archaeological excavations revealing a complex settlement history spanning from Prehistory to the Ottoman period. Notably, Kharayeb's origins can be traced back to the Persian period, when it played a pivotal role in the region's agricultural and economic landscape, culminating in the construction of its Phoenician temple around the 6th century BC.