| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

The Kalamukha were a medieval Shaivite sect of the Deccan Plateau who were among the first professional monks of India. Their earliest monasteries were built in Mysore. [1]

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

The Kalamukha were a medieval Shaivite sect of the Deccan Plateau who were among the first professional monks of India. Their earliest monasteries were built in Mysore. [1]

Information regarding the Kalamukha sect takes the form of inscriptions relating to temple grants and texts usually written by their opponents. They appear to have been an offshoot of the Pashupata sect, about whom more is known. [2] Their name was derived from kālāmukha which has multiple meanings namely, 'facing the time' or 'facing the death' or 'black-face'. Their rituals using "yantras" were more of time based so, we can safely assume the meaning would be one of the first two rather than last one. [3] Evidence from the Puranas and similar ancient texts makes it clear that they were also known by other names, such as Laguda, Lakula and Nakula, and associated with other words meaning black-faced, such as Kalanana. [4]

The rise of the Kalamukhas to a position of influence coincided with the popularisation of the agama texts of Shaivism, and they are shown in the Tirumandiram as one of the six schools of thought to emerge from the agamas. [lower-alpha 1] Theirs was not, however, a school based purely on the agamas as they also took heed of the orthodox Śruti and were well-versed in the Vaisheshika and Nyaya schools. [3] The Kalamukhas were themselves subdivided, with at least two divisions, called the Saktiparisad and the Simhaparisad. The former of these were found over a wide-ranging area and the latter were mostly concentrated around the districts of Dharwar and Shimoga. [5]

According to Ramendra Nath Nandi, the first known record of the Kalamukha sect is a grant issued by the Rashtrakuta dynasty in 807 CE, although he also refers to the existence of a Kalamukha monastery in Mysore in the 8th century. [6] Among the references are a Kalamukha temple recorded in Srinivaspur in 870, another with a college at Chitradurga in 947, and a monastery and temple at Nanjangud by 977. Their major centre was at Balligavi and other temple sites included one at Vijayawada. [7] There is a gap in the recorded evidence of them for around two centuries, after which they are well documented until the Vijayanagara era. [8]

Ramanuja, a Vaishnavite acharya, may have confused the Kalamukha with the Kapalikas in his Sri Bhasya work, in which he noted them as eating from a skull and keeping wine. Such practices were common for the Kapalikas but are atypical for the Kalamukhas. His writings may have been coloured by his experienced of being a member of a different school and being forced by the Kalamukhas and other Shavites to leave his native Tamil Nadu. There was also possibly a desire to discredit because of an element of fear or jealousy driven by the then rising popularity of the Kalamukhas. [9] [10] Nandi notes that:

the Kalamukhas were a saivite sect of social and religious reformers with a strong social basis, whereas the Kapalikas were a sect of self-seekers practising queer and gruesome rites at the cremation ground, away from human localities. [11]

Nonetheless, for many years scholars such as R. G. Bhandarkar believed the Kalamukhas to be a more extreme sect than the Kapalikas, despite acknowledging that Ramanuja's written accounta were confused. David Lorenzen believes this error lay in placing emphasis on Ramanuja's skewed written record above that placed on such epigraphical evidence from inscriptions as had been collated by the time Bhandarkar and others analysed the situation. [12]

Tantra is an esoteric yogic tradition that developed on the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE onwards in both Hinduism and Buddhism.

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions. The feminine form, sometimes used in English, is yogini.

Shaivism is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions ranging from devotional dualistic theism such as Shaiva Siddhanta to yoga-orientated monistic non-theism such as Kashmiri Shaivism. It considers both the Vedas and the Agama texts as important sources of theology. According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, Shaivism is the second-largest Hindu sect, constituting about 253 million or 26.6% of Hindus.

Lingayatism is a Hindu denomination based on Shaivism. Initially known as Veerashaivas, since the 12th-century adherents of this faith are known as Lingayats.

Sadhu, also spelled saddhu, is a religious ascetic, mendicant or any holy person in Hinduism and Jainism who has renounced the worldly life. They are sometimes alternatively referred to as yogi, sannyasi or vairagi.

Nath, also called Natha, are a Shaiva sub-tradition within Hinduism in India and Nepal. A medieval movement, it combined ideas from Buddhism, Shaivism and Yoga traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The Naths have been a confederation of devotees who consider Shiva as their first lord or guru, with varying lists of additional gurus. Of these, the 9th or 10th century Matsyendranatha and the ideas and organization mainly developed by Gorakhnath are particularly important. Gorakhnath is considered the originator of the Nath Panth.

A matha, also written as math, muth, mutth, mutt, or mut, is a Sanskrit word that means 'institute or college', and it also refers to a monastery in Hinduism. An alternative term for such a monastery is adheenam. The earliest epigraphical evidence for mathas related to Hindu-temples comes from the 7th to 10th century CE.

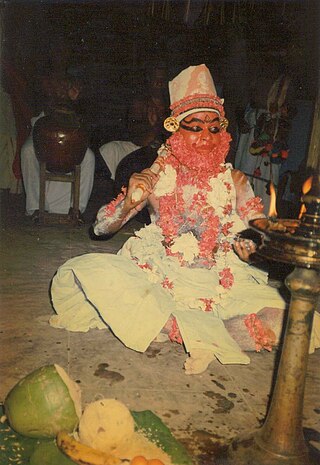

The Kāpālika tradition was a Tantric, non-Puranic form of Shaivism which originated in Medieval India between the 7th and 8th century CE. The word is derived from the Sanskrit term kapāla, meaning "skull", and kāpālika means the "skull-men".

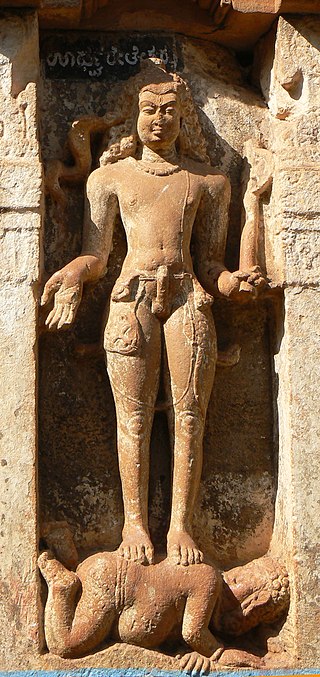

Lakulisha was a prominent Shaivite revivalist, reformist and preceptor of the doctrine of the Pashupatas, one of the oldest sects of Shaivism.

Mattavilasa Prahasana (Devanagari:मत्तविलासप्रहसन), is a short one-act Sanskrit play. It is one of the two great one act plays written by Pallava King Mahendravarman I in the beginning of the seventh century in Tamil Nadu.

Khottiga or Amoghavarsha IV, who bore the title Nityavarsha, was a Rashtrakuta Emperor. During his reign, the Rashtrakutas started to decline. The Paramara King Siyaka II plundered Manyakheta and Khottiga died fighting them. This information is available from the Jain work Mahapurana written by Pushpadanta. He was succeeded by Karka II who only reigned for a few months. In 968 CE, Khottiga installed a panavatta at Danavulapadu Jain temple for the Mahamastakabhisheka of Shantinatha.

Choultry is a resting place, an inn or caravansary for travelers, pilgrims or visitors to a site, typically linked to Buddhist, Jain and Hindu temples. They are also referred to as chottry, choultree, chathra, choltry, chowry, chawari, chawadi, choutry, chowree or tschultri.

Sri Vaishnavism is a denomination within the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism. The name refers to goddess Lakshmi, as well as a prefix that means "sacred, revered", and the god Vishnu, who are together revered in this tradition.

David Neal Lorenzen is a British-American historian, scholar of Religious studies, essayist, and emeritus professor of South Asian history at the Centre for Asian and African studies, El Colegio de México in Mexico City.

Hinduism is the most followed Religion in India and nearly 84% of the total population of Karnataka follows Hinduism, as per 2011 Census of India. Several great empires and dynasties have ruled over Karnataka and many of them have contributed richly to the growth of Hinduism, its temple culture and social development. These developments have reinforced the "Householder tradition", which is of disciplined domesticity, though the saints who propagated Hinduism in the state and in the country were themselves ascetics. The Bhakti movement, of Hindu origin, is devoted to the worship of Shiva and Vishnu; it had a telling impact on the sociocultural ethos of Karnataka from the 12th century onwards.

Bhillama V was the first sovereign ruler of the Seuna (Yadava) dynasty of Deccan region in India. A grandson of the Yadava king Mullagi, he carved out a principality in present-day Maharashtra by capturing forts in and around the Konkan region. Around 1175 CE, he grabbed the Yadava throne, supplanting the descendants of his uncle and an usurper. Over the next decade, he ruled as a nominal vassal of the Chalukyas of Kalyani, raiding the Gujarat Chaulukya and Paramara territories. After the fall of the Chalukya power, he declared sovereignty around 1187 CE, and fought with the Hoysala king Ballala II for control of the former Chalukya territory in present-day Karnataka. Around 1189 CE, he defeated Ballala in a battle at Soratur, but two years later, Ballala defeated him decisively.

Alampuram Papanasi Temples are a group of twenty three Hindu temples dated between 9th- and 11th-century that have been relocated to the southwest of Alampuram village in Telangana. This cluster of mostly ruined temples are co-located near the meeting point of Tungabhadra River and Krishna River at the border of Andhra Pradesh. They are about 1.5 kilometers from the Alampur Navabrahma Temples of the Shaivism tradition, but completed a few centuries later by the Rashtrakutas and later Chalukyas.

The Lakulisa Mathura Pillar Inscription is a 4th-century CE Sanskrit inscription in early Gupta script related to the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism. Discovered near a Mathura well in north India, the damaged inscription is one of the earliest evidences of murti (statue) consecration in a temple made to celebrate gurus. It is, according to the Indologist Michael Willis, crucial to understanding the "history of Pashupata Shaivism" and a floruit for the antiquity of its practices. The Lakulisha Mathura inscription is one of the earliest epigraphical evidence of a developed Shaiva initiation tradition.

The Humcha Jain temples or Humcha basadis are a group of temples found in Humcha village of Shimoga district in Karnataka, India. They were constructed in the 7th century CE in the period of the Santara dynasty and are regarded as one of the major Jain centres of Karnataka. The Padmavati Basadi is the most well-known of these temples.

Notes

Citations

Bibliography