Locksmithing is the work of making and defeating locks. Locksmithing is a traditional trade and in many countries requires completion of an apprenticeship. The level of formal education legally required varies from country to country from none at all, to a simple training certificate awarded by an employer, to a full diploma from an engineering college, in addition to time spent working as an apprentice.

Lock picking is the practice of unlocking a lock by manipulating the components of the lock device without the original key.

A warded lock is a type of lock that uses a set of obstructions, or wards, to prevent the lock from opening unless the correct key is inserted. The correct key has notches or slots corresponding to the obstructions in the lock, allowing it to rotate freely inside the lock.

The pin tumbler lock, also known as the Yale lock after the inventor of the modern version, is a lock mechanism that uses pins of varying lengths to prevent the lock from opening without the correct key.

Engineering tolerance is the permissible limit or limits of variation in:

- a physical dimension;

- a measured value or physical property of a material, manufactured object, system, or service;

- other measured values ;

- in engineering and safety, a physical distance or space (tolerance), as in a truck (lorry), train or boat under a bridge as well as a train in a tunnel ;

- in mechanical engineering, the space between a bolt and a nut or a hole, etc.

A lock is a mechanical or electronic fastening device that is released by a physical object, by supplying secret information, by a combination thereof, or it may only be able to be opened from one side, such as a door chain.

A lever tumbler lock is a type of lock that uses a set of levers to prevent the bolt from moving in the lock. In the simplest form of these, lifting the tumbler above a certain height will allow the bolt to slide past.

A collet is a segmented sleeve, band or collar. One of the two radial surfaces of a collet is usually tapered and the other is cylindrical. The term collet commonly refers to a type of chuck that uses collets to hold either a workpiece or a tool, but collets have other mechanical applications.

A machine taper is a system for securing cutting tools or toolholders in the spindle of a machine tool or power tool. A male member of conical form fits into the female socket, which has a matching taper of equal angle.

Padlocks are portable locks usually with a shackle that may be passed through an opening to prevent use, theft, vandalism or harm.

A key blank is a key that has not been cut to a specific bitting. The blank has a specific cross-sectional profile to match the keyway in a corresponding lock cylinder. Key blanks can be stamped with a manufacturer name, end-user logo or with a phrase, the most commonly seen being 'Do not duplicate'. Blanks are typically stocked by locksmiths for duplicating keys. The profile of the key bow, or the large, flat end, is often characteristic of an individual manufacturer.

Rekeying a lock is replacing the old lock pins with new lock pins.

A wafer tumbler lock is a type of lock that uses a set of flat wafers to prevent the lock from opening unless the correct key is inserted. This type of lock is similar to the pin tumbler lock and works on a similar principle. However, unlike the pin tumbler lock, where each pin consists of two or more pieces, each wafer in the lock is a single piece. The wafer tumbler lock is often incorrectly referred to as a disc tumbler lock, which uses an entirely different mechanism.

The term protector lock has referred to two unrelated lock designs, one invented in the 1850s by Alfred Hobbs, the other in 1874 by Theodor Kromer.

A magnetic keyed lock or magnetic-coded lock is a locking mechanism whereby the key utilizes magnets as part of the locking and unlocking mechanism. Magnetic-coded locks encompass knob locks, cylinder locks, lever locks, and deadbolt locks as well as applications in other security devices.

Engineering fits are generally used as part of geometric dimensioning and tolerancing when a part or assembly is designed. In engineering terms, the "fit" is the clearance between two mating parts, and the size of this clearance determines whether the parts can, at one end of the spectrum, move or rotate independently from each other or, at the other end, are temporarily or permanently joined. Engineering fits are generally described as a "shaft and hole" pairing, but are not necessarily limited to just round components. ISO is the internationally accepted standard for defining engineering fits, but ANSI is often still used in North America.

In mechanical engineering, a key is a machine element used to connect a rotating machine element to a shaft. The key prevents relative rotation between the two parts and may enable torque transmission. For a key to function, the shaft and rotating machine element must have a keyway and a keyseat, which is a slot and pocket in which the key fits. The whole system is called a keyed joint. A keyed joint may allow relative axial movement between the parts.

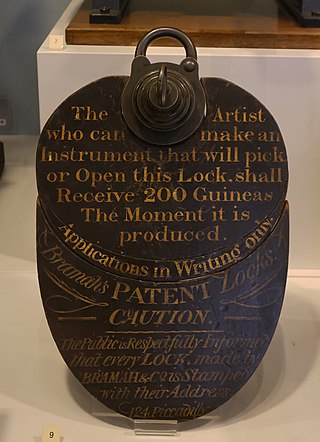

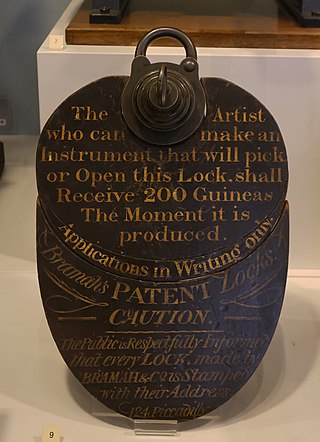

The Bramah lock was created by Joseph Bramah in 1784. The lock employed the first known high-security design.

This is a glossary of locksmithing terms.

Key duplication refers to the process of creating a key based on an existing key. Key cutting is the primary method of key duplication: a flat key is fitted into a vise in a machine, with a blank attached to a parallel vise, and the original key is moved along a guide, while the blank is moved against a blade, which cuts it. After cutting, the new key is deburred: scrubbed with a wire brush, either built into the machine, or in a bench grinder, to remove burrs which, were they not removed, would be dangerously sharp and, further, foul locks.