In United States constitutional law, a regulatory taking occurs when governmental regulations limit the use of private property to such a degree that the landowner is effectively deprived of all economically reasonable use or value of their property. Under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution governments are required to pay just compensation for such takings. The amendment is incorporated to the states via the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court decided 8–1 in favor of the respondent, Edward Schempp, on behalf of his son Ellery Schempp, and declared that school-sponsored Bible reading and the recitation of the Lord's Prayer in public schools in the United States was unconstitutional.

Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 5–4, that the use of eminent domain to transfer land from one private owner to another private owner to further economic development does not violate the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. In the case, plaintiff Susette Kelo sued the city of New London, Connecticut, for violating her civil rights after the city tried to acquire her house's property through eminent domain so that the land could be used as part of a "comprehensive redevelopment plan". Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the five-justice majority that the city's use of eminent domain was permissible under the Takings Clause, because the general benefits the community would enjoy from economic growth qualified as "public use".

Inverse condemnation is a legal concept and cause of action used by property owners when a governmental entity takes an action which damages or decreases the value of private property without obtaining ownership of the property through the use of eminent domain. Thus, unlike the typical eminent domain case, the property owner is the plaintiff and not the defendant.

Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 535 U.S. 302 (2002), is one of the United States Supreme Court's more recent interpretations of the Takings Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The case dealt with the question of whether a moratorium on construction of individual homes imposed by the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency fell under the Takings Clause of the United States Constitution and whether the landowners therefore should receive just compensation as required by that clause. The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency was represented by future Chief Justice John Roberts. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the opinion of the Court, finding that the moratorium did not constitute a taking. It reasoned that there was an inherent difference between the acquisition of property for public use and the regulation of property from private use. The majority concluded that the moratorium at issue in this case should be classified as a regulation of property from private use and therefore no compensation was required.

Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393 (1922), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that whether a regulatory act constitutes a taking requiring compensation depends on the extent of diminution in the value of the property.

Keystone Bituminous Coal Ass'n v. DeBenedictis, 480 U.S. 470 (1987), is a United States Supreme Court case interpreting the Fifth Amendment's Takings Clause. In this case, the court upheld a Pennsylvania statute which limited coal mining causing damage to buildings, dwellings, and cemeteries through subsidence.

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution creates several constitutional rights, limiting governmental powers focusing on criminal procedures. It was ratified, along with nine other articles, in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights.

The Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) is an American nonprofit public interest legal organization established for the purpose of defending and promoting individual and economic freedom. PLF attorneys provide pro bono legal representation, file amicus curiae briefs, and hold administrative proceedings with the stated goal of supporting property rights, equality before the law, freedom of speech and association, economic liberty, and the separation of powers. The organization is the first and oldest libertarian public interest law firm, having been founded in 1973.

Williamson County Regional Planning Commission v. Hamilton Bank of Johnson City, 473 U.S. 172 (1985), is a U.S. Supreme Court case that limited access to federal court for plaintiffs alleging uncompensated takings of private property under the Fifth Amendment. In June 2019, this case was overruled in part by the Court's decision in Knick v. Township of Scott, Pennsylvania.

First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County, 482 U.S. 304 (1987), was a 6–3 decision of the United States Supreme Court. The court held that the complete destruction of the value of property constituted a "taking" under the Fifth Amendment even if that taking was temporary and the property was later restored.

United States v. Causby, 328 U.S. 256 (1946), was a landmark United States Supreme Court decision related to ownership of airspace above private property. The United States government claimed a public right to fly over Thomas Lee Causby's farm located near an airport in Greensboro, North Carolina. Causby argued that the government's low-altitude flights entitled him to just compensation under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

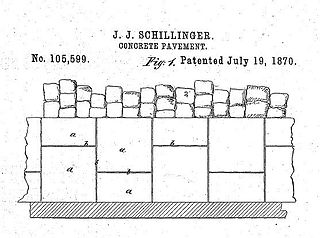

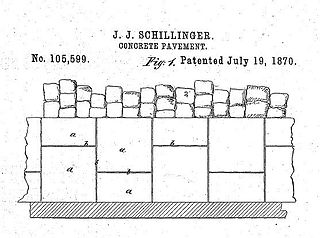

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission v. United States, 568 U.S. 23 (2012), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States holding that it was possible for government-induced, temporary flooding to constitute a "taking" of property under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, such that compensation could be owed to the owner of the flooded property.

Horne v. Department of Agriculture, 569 U.S. 513 (2013) ; 576 U.S. 351 (2015), is a case in which the United States Supreme Court issued two decisions regarding the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The case arose out of a dispute involving the National Raisin Reserve, when a farmer challenged a rule that required farmers to keep a portion of their crops off the market. In Horne I the Court held that the plaintiff had standing to sue for violation of the United States Constitution’s Takings Clause. In Horne II the Court held that the National Raisin Reserve was an unconstitutional violation of the Takings Clause.

Eminent domain in the United States refers to the power of a state or the federal government to take private property for public use while requiring just compensation to be given to the original owner. It can be legislatively delegated by the state to municipalities, government subdivisions, or even to private persons or corporations, when they are authorized to exercise the functions of public character.

Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case that determined that unless they consent, states have sovereign immunity from private suits filed against them in the courts of another state. The 5–4 decision overturned precedent set in a 1979 Supreme Court case, Nevada v. Hall. This was the third time that the litigants had presented their case to the Court, as the Court had already ruled on the issue in 2003 and 2016.