| kp.t Determ: grains, incense in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kyphi, cyphi, or Egyptian cyphi is a compound incense that was used in ancient Egypt for religious and medical purposes.

| kp.t Determ: grains, incense in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kyphi, cyphi, or Egyptian cyphi is a compound incense that was used in ancient Egypt for religious and medical purposes.

Kyphi (Latin : cyphi) is romanized from Greek κυ̑φι for Ancient Egyptian "kap-t", incense, from "kap", to perfume, to cense, to heat, to burn, to ignite. [1] [2] The word root also exists in Indo-European languages, with a similar meaning, like in Sanskrit कपि (kapi) "incense", Greek καπνός "smoke", and Latin vapor. [3] [4]

According to Plutarch (De Iside et Osiride) and Suidas (s. v. Μανήθως), the Egyptian priest Manetho (ca. 300 BCE) is said to have written a treatise called "On the preparation of kyphi" (Περὶ κατασκευη̑ϛ κυφίων), but no copy of this work survives. [5] [6] Three Egyptian kyphi recipes from Ptolemaic times are inscribed on the temple walls of Edfu and Philae. [7]

Greek kyphi recipes are recorded by Dioscorides (De materia medica, I, 24), Plutarch [8] [6] and Galen (De antidotis, II, 2). [7]

The seventh century physician Paul of Aegina records a "lunar" kyphi of twenty-eight ingredients and a "solar" kyphi of thirty-six.[ citation needed ]

The Egyptian recipes have sixteen ingredients each. Dioscorides has ten ingredients, which are common to all recipes. Plutarch gives sixteen, Galen fifteen. Plutarch implies a mathematical significance to the number of sixteen ingredients. [7]

Some ingredients remain obscure. Greek recipes mention aspalathus, which Roman authors describe as a thorny shrub. Scholars do not agree on the identity of this plant: a species of Papilionaceae (Cytisus, Genista or Spartium), [7] Convolvulus scoparius, [7] and Genista acanthoclada [9] have been suggested. The Egyptian recipes similarly list several ingredients whose botanical identity is uncertain.[ citation needed ]

The manufacture of kyphi involves blending and boiling the ingredients in sequence. According to Galen, the result was rolled into balls and placed on hot coals to give a perfumed smoke; it was also drunk as a medicine for liver and lung ailments. [7]

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus Cinnamomum. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, breakfast cereals, snack foods, bagels, teas, hot chocolate and traditional foods. The aroma and flavour of cinnamon derive from its essential oil and principal component, cinnamaldehyde, as well as numerous other constituents including eugenol.

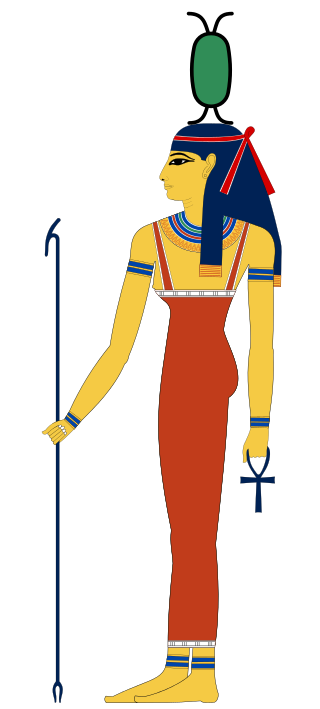

Neith was an ancient Egyptian deity, possibly of Libyan origin. She was connected with warfare, as indicated by her emblem of two crossed bows, and with motherhood, as shown by texts that call her the mother of particular deities, such as the sun god Ra and the crocodile god Sobek. As a mother goddess, she was sometimes said to be the creator of the world. She also had a presence in funerary religion, and this aspect of her character grew over time: she became one of the four goddesses who protected the coffin and internal organs of the deceased.

Hermanubis is a Graeco-Egyptian god who conducts the souls of the dead to the underworld. He is a syncretism of Hermes from Greek mythology and Anubis from Egyptian mythology. Hermanubis was one of the ancestors of the dog-headed Saint Christopher – a cynocephalus saint, which was, similarly to Anubis / Hermanubis, a powerful ferryman for travelers.

Manetho is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third century BC, during the Hellenistic period.

Rice pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and commonly other ingredients such as sweeteners, spices, flavourings and sometimes eggs.

Onycha, along with equal parts of stacte, galbanum, and frankincense, was one of the components of the consecrated Ketoret (incense) which appears in the Torah book of Exodus (Ex.30:34-36) and was used in Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. This formula was to be incorporated as an incense, and was not to be duplicated for non-sacred use. What the onycha of antiquity actually was cannot be determined with certainty. The original Hebrew word used for this component of the ketoret was שחלת, shecheleth, which means "to roar; as a lion " or “peeling off by concussion of sound." Shecheleth is related to the Syriac shehelta which is translated as “a tear, distillation, or exudation.” In Aramaic, the root SHCHL signifies “retrieve.” When the Torah was translated into Greek the Greek word “onycha” ονυξ, which means "fingernail" or "claw," was substituted for shecheleth.

The incense trade route was an ancient network of major land and sea trading routes linking the Mediterranean world with eastern and southern sources of incense, spices and other luxury goods, stretching from Mediterranean ports across the Levant and Egypt through Northern East Africa and Arabia to India and beyond. These routes collectively served as channels for the trading of goods such as Arabian frankincense and myrrh; Indian spices, precious stones, pearls, ebony, silk and fine textiles; and from the Horn of Africa, rare woods, feathers, animal skins, Somali frankincense, gold, and slaves. The incense land trade from South Arabia to the Mediterranean flourished between roughly the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD.

Iraqi cuisine is a Middle Eastern cuisine that has its origins in the ancient Near East culture of the fertile crescent. Tablets found in ancient ruins in Iraq show recipes prepared in the temples during religious festivals—the first cookbooks in the world. Ancient Iraq's cultural sophistication extended to the culinary arts.

Balm of Gilead was a rare perfume used medicinally that was mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and named for the region of Gilead, where it was produced. The expression stems from William Tyndale's language in the King James Bible of 1611 and has come to signify a universal cure in figurative speech. The tree or shrub producing the balm is commonly identified as Commiphora gileadensis. However, some botanical scholars have concluded that the actual source was a terebinth tree in the genus Pistacia.

Theriac or theriaca is a medical concoction originally labelled by the Greeks in the 1st century AD and widely adopted in the ancient world as far away as Persia, China and India via the trading links of the Silk Route. It was an alexipharmic, or antidote for a variety of poisons and diseases. It was also considered a panacea, a term for which it could be used interchangeably: in the 16th century Adam Lonicer wrote that garlic was the rustic's theriac or Heal-All.

The word perfume is used today to describe scented mixtures and is derived from the Latin word per fumus. The word perfumery refers to the art of making perfumes. Perfume was produced by ancient Greeks, and perfume was also refined by the Romans, the Persians and the Arabs. Although perfume and perfumery also existed in East Asia, much of its fragrances were incense based. The basic ingredients and methods of making perfumes are described by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia.

Stacte and nataph are names used for one component of the Solomon's Temple incense, the Ketoret, specified in the Book of Exodus. Variously translated to the Greek term or to an unspecified "gum resin" or similar, it was to be mixed in equal parts with onycha, galbanum and mixed with pure frankincense and they were to "beat some of it very small" for burning on the altar of the tabernacle.

The incense offering in Judaism was related to perfumed offerings on the altar of incense in the time of the Tabernacle and the First and Second Temple period, and was an important component of priestly liturgy in the Temple in Jerusalem.

John Gwyn Griffiths was a Welsh poet, Egyptologist and nationalist political activist who spent the largest span of his career lecturing at Swansea University.

Mastic is a resin obtained from the mastic tree. It is also known as tears of Chios, being traditionally produced on the island Chios, and, like other natural resins, is produced in "tears" or droplets.

The Leyden papyrus X is a papyrus codex written in Greek at about the end of the 3rd century A.D. or perhaps around 250 A.D. and buried with its owner, and today preserved at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

De materia medica is a pharmacopoeia of medicinal plants and the medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until supplanted by revised herbals in the Renaissance, making it one of the longest-lasting of all natural history and pharmacology books.

The incense offering, a blend of aromatic substances that exhale perfume during combustion, usually consisting of spices and gums burnt as an act of worship, occupied a prominent position in the sacrificial legislation of the ancient Hebrews.

The history of spices reach back thousands of years, dating back to the 8th century B.C. Spices are widely known to be developed and discovered in Asian civilizations. Spices have been used in a variety of antique developments for their unique qualities. There were a variety of spices that were used for common purposes across the ancient world. Different spices hold a value that can create a variety of products designed to enhance or suppress certain taste and/or sensations. Spices were also associated with certain rituals to perpetuate a superstition or fulfill a religious obligation, among other things.