Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, also known as the Great Earl of Cork, was an English politician who served as Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom of Ireland.

Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery, 25 April 1621 to 16 October 1679, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and politician. A younger son of the Earl of Cork, the largest landowner in Munster, like many Irish Protestants he supported the Dublin Castle administration during the Irish Confederate Wars, a related conflict of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

The Irish Confederate Wars, also called the Eleven Years' War, took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in the kingdoms of Ireland, England and Scotland – all ruled by Charles I. The conflict had political, religious and ethnic aspects and was fought over governance, land ownership, religious freedom and religious discrimination. The main issues were whether Irish Catholics or British Protestants held most political power and owned most of the land, and whether Ireland would be a self-governing kingdom under Charles I or subordinate to the parliament in England. It was the most destructive conflict in Irish history and caused 200,000–600,000 deaths from fighting as well as war-related famine and disease.

King John's Castle also known as Limerick Castle is a 13th-century castle located on King's Island in Limerick, Ireland, next to the River Shannon. Although the site dates back to 922 when the Vikings lived on the Island, the castle itself was built on the orders of King John of England in 1200. One of the best preserved Norman castles in Europe, the walls, towers and fortifications remain today and are visitor attractions. The remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during archaeological excavations at the site in 1900.

The battle of Knocknaclashy, took place in County Cork in southern Ireland in 1651. In it, an Irish Confederate force led by Viscount Muskerry was defeated by an English Parliamentarian force under Lord Broghill. It was the final pitched battle of the Irish Confederate Wars and one of the last of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

The Battle of Macroom was a skirmish fought on 10 May 1650, near Macroom, County Cork, in southern Ireland, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. An English Parliamentarian force under Roger Boyle,, defeated an Irish Confederate force under David Roche.

Nicholas Brady, Anglican divine and poet, was born in Bandon, County Cork, Ireland. He was the second son of Irishman Major Nicholas Brady and his wife Martha Gernon, daughter of the English-born judge and author Luke Gernon ; his great-grandfather was Hugh Brady, the first Protestant Bishop of Meath. He received his education at Westminster School and at Christ Church, Oxford; he had degrees from Trinity College, Dublin

William Maziere Brady (1825–1894) was an Irish priest, ecclesiastical historian and journalist who converted to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism.

Richard Townesend was a soldier and politician in England. He was born in 1618 or 1619. Much research has been undertaken by various members of the Townsend family to trace Richard's origins but nothing is known about him before 1643 when he was appointed to command a company, as a captain, in Colonel Ceely's Regiment, which had been raised to garrison Lyme Regis. Richard was engaged in several skirmishes, most notably on 3 March 1643 when he surprised and routed 150 Royalist cavalry at Bridport. Later, he was present during the defence of Lyme Regis 20 April – 13 June 1644 where he distinguished himself and was promoted to Major. In 1645 he assumed command of Colonel Ceely's Regt when Colonel Ceely was returned to Parliament as Member of Parliament (MP) for Bridport.

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munster, the Nine Years' War, and the Irish Rebellion of 1641. The Lord President was subject to the Lord Deputy of Ireland, but had full authority within the province, extending to civil, criminal, and church legal matters, the imposition of martial law, official appointments, and command of military forces. Some appointments to military governor of Munster were not accompanied by the status of President. The width of his powers led to frequent clashes with the longer established courts, and in 1622 the President, Donogh O'Brien, 4th Earl of Thomond, was warned sharply not to "intermeddle" with cases which were properly the business of those courts. He was assisted by a Council whose members included the Chief Justice of Munster, another justice and the Attorney General for the Province. By 1620 his council was permanently based in Limerick.

Murrough MacDermod O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin, was an Irish nobleman and soldier, who came from one of the most powerful families in Munster. Known as Murchadh na dTóiteán, he initially trained for war in the Spanish service. He accompanied the Earl of Strafford into Leinster on the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and was appointed governor of Munster in 1642. He had some small success, but was hampered by lack of funds and he was outwitted by the Irish leader, Viscount Muskerry, at Cappoquin and Lismore. His forces dispersed at the truce of 1643.

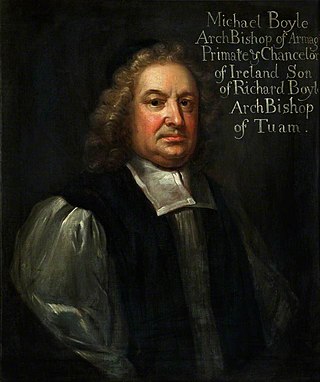

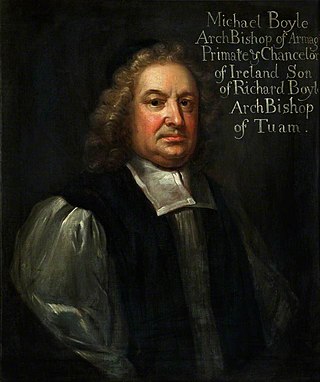

Michael Boyle, the younger was a Church of Ireland bishop who served as Archbishop of Dublin from 1663 to 1679 and Archbishop of Armagh from 1679 to his death. He also served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, the last time a bishop was appointed to that office.

Sir Maziere Brady, 1st Baronet, PC (Ire) was an Irish judge, notable for his exceptionally long, though not particularly distinguished tenure as Lord Chancellor of Ireland.

Sir Richard Pyne was an Irish landowner, barrister and judge. He held office as Lord Chief Justice of Ireland from 1695-1709.

Sir Thomas Crooke, 1st Baronet, of Baltimore (1574–1630) was an English-born politician, lawyer and landowner in seventeenth-century Ireland. He is chiefly remembered as the founder of the town of Baltimore, County Cork, which he developed into a flourishing port, but which was largely destroyed shortly after his death in the Sack of Baltimore 1631. He sat in the Irish House of Commons as member for Baltimore in the Parliament of 1613–1615. He was the first of the Crooke baronets of Baltimore, and ancestor of the Crooke family of Crookstown House.

William Saxey or Saxei was an English-born judge in Ireland of the late Elizabethan and early Stuart era. He was an unpopular and controversial figure with a reputation for corruption and misanthropy.

The chief justice of Munster was the senior of the two judges who assisted the Lord President of Munster in judicial matters. Despite his title of Chief Justice, full judicial authority was vested in the lord president, who had "power to hear and determine at his discretion all manner of complaints in any part of the province of Munster", and also had powers to hold commissions of oyer and terminer and gaol delivery.

Sir Robert Travers was an Irish judge, soldier and politician of the early seventeenth century. Despite his unenviable reputation for corruption, he had a highly successful career until the outbreak of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, when he went into opposition to King Charles I. He fought on the side of the Irish Parliament, and was killed at the Battle of Knocknanuss. He was a nephew of the poet Edmund Spenser, and was the founder of a notable military dynasty.

William Halsey was a politician, soldier and judge in seventeenth-century Ireland. He was Mayor of Waterford, a member of each of the three Protectorate Parliaments, and the last Chief Justice of Munster.

Sir Lawrence Parsons was an English-born barrister, judge and politician in seventeenth-century Ireland, who enjoyed a highly successful career, despite frequent accusations of corruption and neglect of official duty. His success owed much to the patronage of his uncle Sir Geoffrey Fenton, of his cousin by marriage Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, and of the prime Royal favourite, the Duke of Buckingham. He was the ancestor of the Earl of Rosse of the second creation. He rebuilt Birr Castle, which is still the Parsons family home.