The Arzhang, also known as the Book of Pictures, was one of the holy books of Manichaeism. It was written and illustrated by its prophet, Mani, in Syriac, with later reproductions written in Sogdian. It was unique as a sacred text in that it contained numerous pictures designed to portray Manichaean cosmogony, which were regarded as integral to the text.

Chinese Manichaeism, also known as Monijiao (Chinese: 摩尼教; pinyin: Móníjiào; Wade–Giles: Mo2-ni2 Chiao4; lit. 'religion of Moni') or Mingjiao (Chinese: 明教; pinyin: Míngjiào; Wade–Giles: Ming2-Chiao4; lit. 'religion of light or 'bright religion'), is the form of Manichaeism transmitted to and currently practiced in China. Chinese Manichaeism rose to prominence during the Tang dynasty and despite frequent persecutions, it has continued long after the other forms of Manichaeism were eradicated in the West. The most complete set of surviving Manichaean writings were written in Chinese sometime before the 9th century and were found in the Mogao Caves among the Dunhuang manuscripts.

The Manichaean Diagram of the Universe is a Yuan dynasty silk painting describing the cosmology of Manichaeism, in other words, the structure of universe according to Manichaean vision. The painting in vivid colours on a silk cloth survives in three parts, whose proper relation to one another and digital reconstruction was published by Zsuzsanna Gulácsi.

Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation is a Yuan dynasty silk hanging scroll, measuring 142 × 59 centimetres and dating from the 13th century, with didactic themes: a multi-scenic narrative that depicts Mani's Teachings about the Salvation combines a sermon subscene with the depictions of soteriological teaching in the rest of the painting.

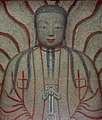

The Manichaean Painting of the Buddha Jesus (Chinese: 夷數佛幀; pinyin: Yí shù fó zhēn; Wade–Giles: I2-shu4 fo2-chên1; Japanese: キリスト聖像; rōmaji: Kirisuto Sei-zō; lit. 'Sacred Image of Christ'), is a Chinese Southern Song dynasty silk hanging scroll preserved at the Seiunji Temple in Kōshū, Yamanashi, Japan. It measures 153.5 cm in height, 58.7 cm in width, dates from the 12th to 13th centuries, and depicts a solitary nimbate figure on a dark-brown medieval Chinese silk. According to the Hungarian historian Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, this painting is one of the six documented Chinese Manichaean hanging scrolls from Zhejiang province from the early 12th century, which titled Yishu fo zhen (lit. "Silk Painting of the Buddha [Prophet] Jesus").

Zsuzsanna Gulácsi is a Hungarian-born American historian, art historian of pan-Asiatic religions. She is a professor of art history, Asian studies, and comparative religious studies at Northern Arizona University (NAU). Her teaching covers Early and Eastern Christian art, Islamic art, with special attention to the medium of the illuminated book; as well as late ancient and mediaeval Buddhist art from South, Central, and East Asia.

In Manichaeism, Jesus is considered one of the four prophets of the faith, along with Zoroaster, Gautama Buddha and Mani. He is also a "guiding deity" who greets the light bodies of the righteous after their deliverance.

Manichaean Temple Banner Number "MIK Ⅲ 6286" is a Manichaean monastery flag banner collected in Berlin Asian Art Museum, made in the 10th century AD. It was found in Xinjiang Gaochang by a German Turpan expedition team at the beginning of the 20th century. The flag streamer is 45.5 cm long and 16 cm wide, with painted portraits on both sides. It is a funeral streamer dedicated to the deceased Manichae believers.

The Birth of Mani is a Manichean silk cloth color painting painted in the Fujian Zhejiang area during the Yuan period, depicting the founder of the sect Mani The scene of birth, a scholar who specializes in Manichaeism Ma Xiaohe called it "a rare treasure". This picture is now in the collection of Japan Kyushu National Museum. The drawing technique and artistic style are similar to "Mani's Community Established" and "Mani's Parents", "The Birth of Mani" and "Manichean Universe Map". " It was originally part of a large-scale Manichean silk painting; however, now the silk painting has been lost, leaving only the birth picture.

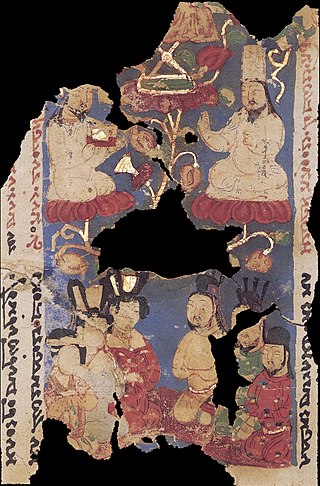

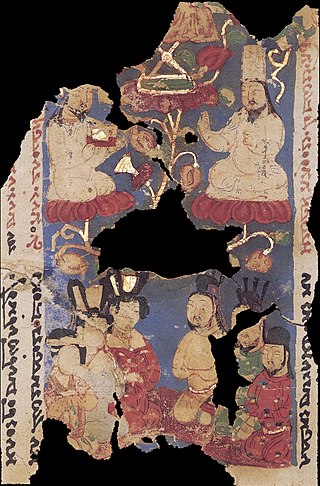

Episodes from Mani's Missionary Work is a Manichean silk color painting drawn in the coastal area of southern China during the yuan to ming period. It is now in a private Japanese collection. The whole picture can be roughly divided into five scenes, depicting the missionary process of a Manichean elector. According to Hungary Asian religious art historian Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, this priest is probably the founder of Manichaeism Mani himself. This painting was originally part of a large-scale Manichean silk painting. The drawing technique and artistic style are similar to "Mani's Community Established" and "Mani's Parents", "The Birth of Mani" and "Manichean Universe Map".

Icon of Mani is a silk painting hanging scroll from the Yuan or Ming period, from the coastal area of southern China, depicting Mani. The portrait of the founder Mani has been completely Sinicized.

Leaf from a Manichaean book MIK III 4974 is a fragment of Manichaean manuscripts collected in Germany Berlin Asian Art Museum, drawn in the 10th century, 20 At the beginning of the century, it was discovered by German Turpan expedition team in Xinjiang Gaochang Ancient City. The remaining page is 7.9 cm long and 15.5 cm wide, with an illuminated manuscript illustration drawn in the center of the front. The upper part of the book is written with Middle Persian Benediction The scriptures indicate that this fragment originally belonged to a Manichae Liturgical book.

Mani's Community Established is a Manichaen silk color painting drawn in the coastal area of southern China during the yuan to ming period, depicts the missionary history of Manichaeism and the establishment of its churches in three scenes. The preservation is intact and undamaged. This painting was originally part of a large Manichae silk painting, The drawing technique and artistic style are very similar to "Episodes from Mani's Missionary Work", "The Birth of Mani", "Mani's Parents" and "The Manichean Universe Map". The painting is now in a private collection in Japan.

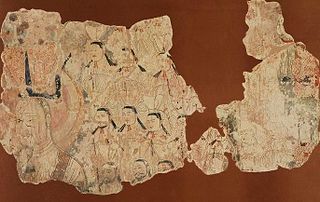

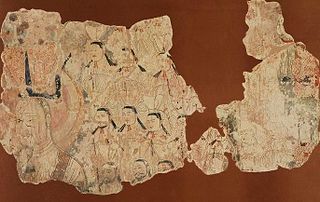

Mani's Parents is a color painting on silk drawn in the coastal areas of southern China during the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties. It is in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, US, and was donated by Ivory Brendage. The title given on the official website of the museum is "Fragment of a Manichaen Mandala".

Fragment of Manichaean Wall Painting "MIK Ⅲ 6918" is a fragment of a Manichaean mural collected in Germany Berlin Asian Art Museum, painted around the 10th century AD, and was found by the German Turpan expedition team in the ruins of Gaochang, in Xinjiang. The fragment is 88 centimeters long and 168.5 centimeters wide. It depicts a scene of worship in a Manichae church.

The crystal seal of Mani, also known as the crystal sealstone of Mani or the Manichean Rock-Crystal Seal, is a crystal stone seal with intaglio busts of three Manichean elect. There is a circle of Syriac writing around the intaglio, which could have been a personal seal used by Mani, the founder of Manichaeism. It is the oldest surviving piece of Manichaean art, and the only piece from Sassanid Mesopotamia. It is now in the collection of the National Library of France in Paris.

Leaf from a Manichaean book MIK III 8259 is a fragment of Manichaean manuscripts collected in Germany Berlin Asian Art Museum, drawn during the 8th–9th centuries. It was discovered in Xinjiang by German Turpan expedition team in the early 20th century. It is the largest currently known manuscript fragment, and is also the largest codex fragment with a figural scene, having a large portion of text on the same fragment. There is also text on the reverse of the image.

The Manichaean Turpan documents found in Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves include many documents and works of Manichaean art found by the German Turfan expeditions.

In Manichaeism, Siddartha Gautama is considered one of the four prophets of the faith, along with Zoroaster, Jesus and Mani. Mani believed that the teachings of Gautama Buddha, Zoroaster, and Jesus were incomplete, and that his revelations were for the entire world, calling his teachings the "Religion of Light".

In Manichaeism, Zarathustra is considered one of the four prophets of the faith, along with Buddha, Jesus and Mani. Mani believed that the teachings of Gautama Buddha, Zarathustra, and Jesus were incomplete, and that his revelations were for the entire world, calling his teachings the "Religion of Light".