Mechanism

MesPGN often occurs as a result of glomerular injury, though can be idiopathic. MesPGN has been associated with disease processes such as: IgA nephropathy, IgM nephropathy, systemic lupus erythematous, Alport syndrome, resolving post-infectious glomerulonephritis, and complement nephropathy, such as C1Q nephropathy. [1]

IgA nephropathy is the most common cause of MesPGN. [3] It is thought abnormally glycosylated IgA form polymers and deposit in the mesangium. [3] Subsequently, IgA immune complexes bind to IgA receptors on mesangial cells and induce injury to mesangial cells through release of cytokines and growth factors that promote infiltration of leukocytes, mesangial cell proliferation, and mesangial matrix expansion. [3]

In the context of resolving post-infectious glomerulonephritis, MesPGN can be seen after an infection with a nephritogenic strain of group A streptococci. [4] Pathogenesis of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis includes injury to the glomerulus by immune complexes (IgG) passively trapped in the glomerulus, which leads to an inflammatory response from recruited immune cells, cytokines, chemical mediators, and complement and coagulation cascade activation. [5] The inflammatory response includes endothelial and mesangial cell proliferation. [3]

Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis of lupus nephritis, Class II is also noted by mesangial hypercellularity and matrix expansion. Microscopic hematuria with or without proteinuria may be seen in Class II lupus nephritis. Hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and acute kidney injury are very rare at this stage. [6]

Idiopathic mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis is less established in the literature. Idiopathic mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis does not involve the deposition of either IgA or IgG immune complexes, though there can be focal or diffuse IgM deposits in the mesangium. [7] The relationship of IgM and mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis is hypothesized to involve either formed or deposited IgM complexes in the mesangium leading to T-cell mediated inflammatory response, mesangial proliferation, and glomerular injury or, as a result of mesangial proliferation, decreased clearance of monocytic IgM complexes. [7]

Diagnosis

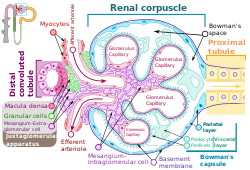

Most glomerulonephritis' classification and prognosis are aided by histological evaluation by renal biopsy. [3] The renal biopsy is classically evaluated with light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunohistology to diagnose a histological pattern, which is then compared to clinical evaluation through history, physical, and laboratory evaluation. [3] The laboratory evaluation usually follows that of a standard nephrology work up and will likely be targeted to a differential diagnosis. Studies focusing on mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis often use defined clinical criteria and histological criteria to select patients for research. For example, one study used the following histological criteria: "Glomeruli with mesangial hypercellularity (four or more cells/mesangium with or without mesangial matrix expansion and immune complex deposits)". [1] The histologic pattern of injury can also provide insight into the prognosis of the glomerular disorder. Mesangial proliferation indicates a mild, though active, lesion. [8] Overall, a kidney biopsy should address the following: [8]

- Primary diagnosis, with clinical modifiers

- Pattern of injury

- Established score/class/grade of disease entities (i.e., lupus nephritis, IgA nephropathy)

- Secondary diagnosis (i.e., ATN, interstitial nephritis, thrombotic microangiopathy)

- Ancillary studies, if done (i.e., IgG sub typing)

- Chronicity grade and score

The kidney biopsy is foundational to informing the diagnosis of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, as it is a morphological pattern.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.