Proteinuria is the presence of excess proteins in the urine. In healthy persons, urine contains very little protein, less than 150 mg/day; an excess is suggestive of illness. Excess protein in the urine often causes the urine to become foamy. Severe proteinuria can cause nephrotic syndrome in which there is worsening swelling of the body.

Nephrotic syndrome is a collection of symptoms due to kidney damage. This includes protein in the urine, low blood albumin levels, high blood lipids, and significant swelling. Other symptoms may include weight gain, feeling tired, and foamy urine. Complications may include blood clots, infections, and high blood pressure.

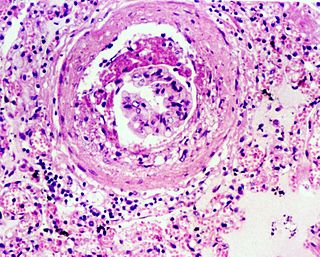

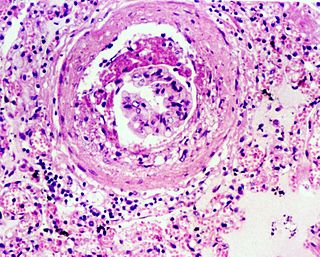

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), also known as Berger's disease, or synpharyngitic glomerulonephritis, is a disease of the kidney and the immune system; specifically it is a form of glomerulonephritis or an inflammation of the glomeruli of the kidney. Aggressive Berger's disease can attack other major organs, such as the liver, skin and heart.

Podocytes are cells in Bowman's capsule in the kidneys that wrap around capillaries of the glomerulus. Podocytes make up the epithelial lining of Bowman's capsule, the third layer through which filtration of blood takes place. Bowman's capsule filters the blood, retaining large molecules such as proteins while smaller molecules such as water, salts, and sugars are filtered as the first step in the formation of urine. Although various viscera have epithelial layers, the name visceral epithelial cells usually refers specifically to podocytes, which are specialized epithelial cells that reside in the visceral layer of the capsule.

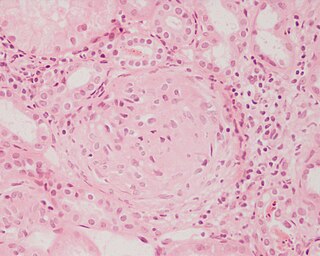

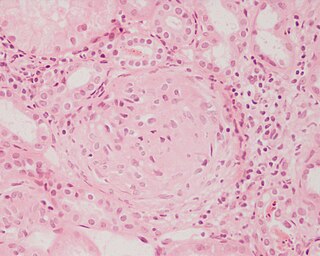

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a term used to refer to several kidney diseases. Many of the diseases are characterised by inflammation either of the glomeruli or of the small blood vessels in the kidneys, hence the name, but not all diseases necessarily have an inflammatory component.

Diabetic nephropathy, also known as diabetic kidney disease, is the chronic loss of kidney function occurring in those with diabetes mellitus. Diabetic nephropathy is the leading causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) globally. The triad of protein leaking into the urine, rising blood pressure with hypertension and then falling renal function is common to many forms of CKD. Protein loss in the urine due to damage of the glomeruli may become massive, and cause a low serum albumin with resulting generalized body swelling (edema) so called nephrotic syndrome. Likewise, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) may progressively fall from a normal of over 90 ml/min/1.73m2 to less than 15, at which point the patient is said to have end-stage renal disease. It usually is slowly progressive over years.

Hypertensive kidney disease is a medical condition referring to damage to the kidney due to chronic high blood pressure. It manifests as hypertensive nephrosclerosis. It should be distinguished from renovascular hypertension, which is a form of secondary hypertension, and thus has opposite direction of causation.

Membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) is a slowly progressive disease of the kidney affecting mostly people between ages of 30 and 50 years, usually white people.

HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) refers to kidney disease developing in association with infection by human immunodeficiency virus, the virus that causes AIDS. The most common, or "classical", type of HIV-associated nephropathy is a collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), though other forms of kidney disease may also occur. Regardless of the underlying histology, kidney disease in HIV-positive patients is associated with an increased risk of death.

Congenital nephrotic syndrome is a rare kidney disease which manifests in infants during the first 3 months of life, and is characterized by high levels of protein in the urine (proteinuria), low levels of protein in the blood, and swelling. This disease is primarily caused by genetic mutations which result in damage to components of the glomerular filtration barrier and allow for leakage of plasma proteins into the urinary space.

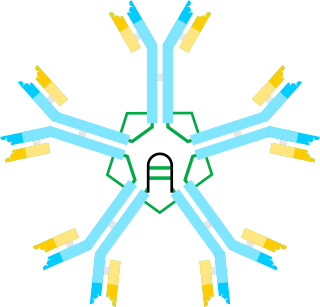

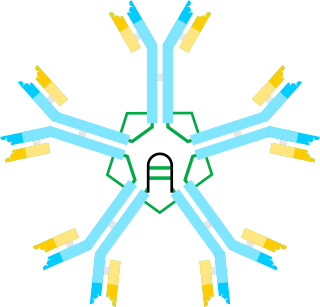

Nephrin is a protein necessary for the proper functioning of the renal filtration barrier. The renal filtration barrier consists of fenestrated endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane, and the podocytes of epithelial cells. Nephrin is a transmembrane protein that is a structural component of the slit diaphragm. It is present on the tips of the podocytes as an intricate mesh connecting adjacent foot processes. Nephrin contributes to the strong size selectivity of the slit diaphragm, however, the relative contribution of the slit diaphragm to exclusion of protein by the glomerulus is debated. The extracellular interactions, both homophilic and heterophilic—between nephrin and NEPH1—are not completely understood. In addition to eight immunoglobulin G–like motifs and a fibronectin type 3 repeat, nephrin has a single transmembrane domain and a short intracellular tail. Tyrosine phosphorylation at different sites on the intracellular tail contribute to the regulation of slit diaphragm formation during development and repair in pathology affecting podocytes. Podocin may interact with nephrin to guide it onto lipid rafts in podocytes, requiring the integrity of an arginine residue of nephrin at position 1160.

The glomerular basement membrane of the kidney is the basal lamina layer of the glomerulus. The glomerular endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane, and the filtration slits between the podocytes perform the filtration function of the glomerulus, separating the blood in the capillaries from the filtrate that forms in Bowman's capsule. The glomerular basement membrane is a fusion of the endothelial cell and podocyte basal laminas, and is the main site of restriction of water flow. Glomerular basement membrane is secreted and maintained by podocyte cells.

Podocin is a protein component of the filtration slits of podocytes. Glomerular capillary endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane and the filtration slits function as the filtration barrier of the kidney glomerulus. Mutations in the podocin gene NPHS2 can cause nephrotic syndrome, such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) or minimal change disease (MCD). Symptoms may develop in the first few months of life or later in childhood.

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is a type of glomerulonephritis caused by deposits in the kidney glomerular mesangium and basement membrane (GBM) thickening, activating the complement system and damaging the glomeruli.

Glomerulosclerosis is the hardening of the glomeruli in the kidney. It is a general term to describe scarring of the kidneys' tiny blood vessels, the glomeruli, the functional units in the kidney that filter urea from the blood.

Podocin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the NPHS2 gene.

Glomerulopathy is a disease that impacts the glomeruli in the nephron, either inflammatory or noninflammatory. Glomerulopathy includes collapsing glomerulopathy, glomerulocystic kidney disease, glomerulomegaly, membranous nephropathy, and tip lesion glomerulopathy.

Glomerulonephrosis is a non-inflammatory disease of the kidney (nephrosis) presenting primarily in the glomerulus as nephrotic syndrome. The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney and it contains the glomerulus, which acts as a filter for blood to retain proteins and blood lipids. Damage to these filtration units results in important blood contents being released as waste in urine. This disease can be characterized by symptoms such as fatigue, swelling, and foamy urine, and can lead to chronic kidney disease and ultimately end-stage renal disease, as well as cardiovascular diseases. Glomerulonephrosis can present as either primary glomerulonephrosis or secondary glomerulonephrosis.

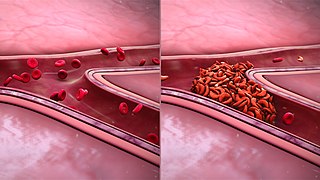

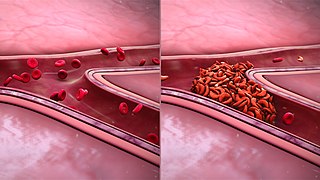

Sickle cell nephropathy is a type of kidney disease associated with sickle cell disease which causes kidney complications as a result of sickling of red blood cells in the small blood vessels. The hypertonic and relatively hypoxic environment of the renal medulla, coupled with the slower blood flow in the vasa recta, favors sickling of red blood cells, with resultant local infarction. Functional tubule defects in patients with sickle cell disease are likely the result of partial ischemic injury to the renal tubules.

IgM nephropathy or immunoglobulin M nephropathy (IgMN) is a kind of idiopathic glomerulonephritis that is marked by IgM diffuse deposits in the glomerular mesangium. IgM nephropathy was initially documented in 1978 by two separate teams of researchers.