The human urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The urinary tract is the body's drainage system for the eventual removal of urine. The kidneys have an extensive blood supply via the renal arteries which leave the kidneys via the renal vein. Each kidney consists of functional units called nephrons. Following filtration of blood and further processing, wastes exit the kidney via the ureters, tubes made of smooth muscle fibres that propel urine towards the urinary bladder, where it is stored and subsequently expelled through the urethra during urination. The female and male urinary system are very similar, differing only in the length of the urethra.

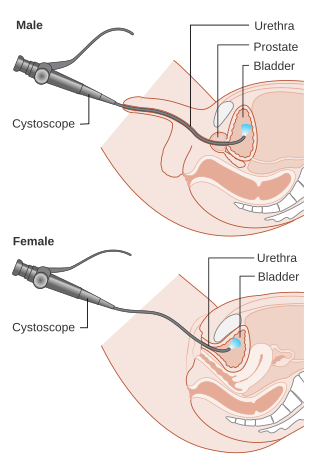

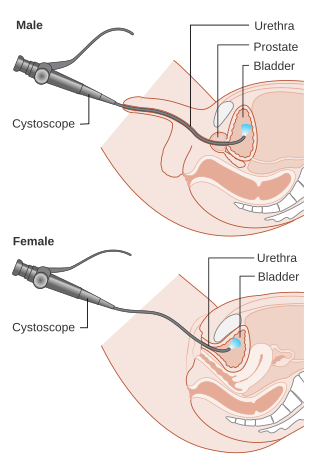

Cystoscopy is endoscopy of the urinary bladder via the urethra. It is carried out with a cystoscope.

In urinary catheterization, a latex, polyurethane, or silicone tube known as a urinary catheter is inserted into the bladder through the urethra to allow urine to drain from the bladder for collection. It may also be used to inject liquids used for treatment or diagnosis of bladder conditions. A clinician, often a nurse, usually performs the procedure, but self-catheterization is also possible. A catheter may be in place for long periods of time or removed after each use.

Urinalysis, a portmanteau of the words urine and analysis, is a panel of medical tests that includes physical (macroscopic) examination of the urine, chemical evaluation using urine test strips, and microscopic examination. Macroscopic examination targets parameters such as color, clarity, odor, and specific gravity; urine test strips measure chemical properties such as pH, glucose concentration, and protein levels; and microscopy is performed to identify elements such as cells, urinary casts, crystals, and organisms.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), also known as Berger's disease, or synpharyngitic glomerulonephritis, is a disease of the kidney and the immune system; specifically it is a form of glomerulonephritis or an inflammation of the glomeruli of the kidney. Aggressive Berger's disease can attack other major organs, such as the liver, skin and heart.

Dysuria refers to painful or uncomfortable urination.

Hydronephrosis describes hydrostatic dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces as a result of obstruction to urine flow downstream. Alternatively, hydroureter describes the dilation of the ureter, and hydronephroureter describes the dilation of the entire upper urinary tract.

Nephritic syndrome is a syndrome comprising signs of nephritis, which is kidney disease involving inflammation. It often occurs in the glomerulus, where it is called glomerulonephritis. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation and thinning of the glomerular basement membrane and the occurrence of small pores in the podocytes of the glomerulus. These pores become large enough to permit both proteins and red blood cells to pass into the urine. By contrast, nephrotic syndrome is characterized by proteinuria and a constellation of other symptoms that specifically do not include hematuria. Nephritic syndrome, like nephrotic syndrome, may involve low level of albumin in the blood due to the protein albumin moving from the blood to the urine.

Microhematuria, also called microscopic hematuria, is a medical condition in which urine contains small amounts of blood; the blood quantity is too low to change the color of the urine. While not dangerous in itself, it may be a symptom of kidney disease, such as IgA nephropathy or Sickle cell trait, which should be monitored by a doctor.

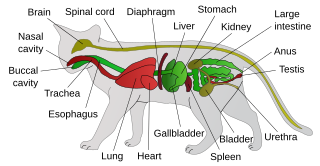

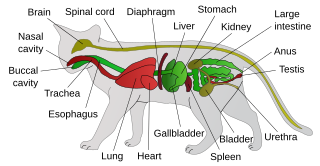

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is a generic category term to describe any disorder affecting the bladder or urethra of cats.

Hemorrhagic cystitis or haemorrhagic cystitis is an inflammation of the bladder defined by lower urinary tract symptoms that include dysuria, hematuria, and hemorrhage. The disease can occur as a complication of cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide and radiation therapy. In addition to hemorrhagic cystitis, temporary hematuria can also be seen in bladder infection or in children as a result of viral infection.

A ureteral stent, or ureteric stent, is a thin tube inserted into the ureter to prevent or treat obstruction of the urine flow from the kidney. The length of the stents used in adult patients varies between 24 and 30 cm. Additionally, stents come in differing diameters or gauges, to fit different size ureters. The stent is usually inserted with the aid of a cystoscope. One or both ends of the stent may be coiled to prevent it from moving out of place; this is called a JJ stent, double J stent or pig-tail stent.

Pyelogram is a form of imaging of the renal pelvis and ureter.

Loin pain hematuria syndrome (LPHS) is the combination of debilitating unilateral or bilateral flank pain and microscopic or macroscopic amounts of blood in the urine that is otherwise unexplained.

Bacteriuria is the presence of bacteria in urine. Bacteriuria accompanied by symptoms is a urinary tract infection while that without is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria. Diagnosis is by urinalysis or urine culture. Escherichia coli is the most common bacterium found. People without symptoms should generally not be tested for the condition. Differential diagnosis include contamination.

Urologic diseases or conditions include urinary tract infections, kidney stones, bladder control problems, and prostate problems, among others. Some urologic conditions do not affect a person for that long and some are lifetime conditions. Kidney diseases are normally investigated and treated by nephrologists, while the specialty of urology deals with problems in the other organs. Gynecologists may deal with problems of incontinence in women.

A urine test strip or dipstick is a basic diagnostic tool used to determine pathological changes in a patient's urine in standard urinalysis.

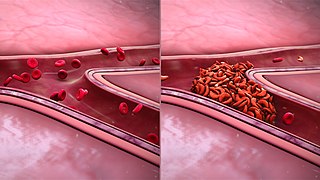

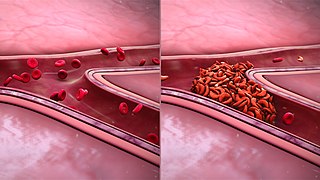

Sickle cell nephropathy is a type of kidney disease associated with sickle cell disease which causes kidney complications as a result of sickling of red blood cells in the small blood vessels. The hypertonic and relatively hypoxic environment of the renal medulla, coupled with the slow blood flow in the vasa recta, favors sickling of red blood cells, with resultant local infarction. Functional tubule defects in patients with sickle cell disease are likely the result of partial ischemic injury to the renal tubules.

Fraley syndrome is a condition where the superior infundibulum of the upper calyx of the kidney is obstructed by the crossing renal artery branch, causing distension and dilatation of the calyx and presenting clinically as haematuria and nephralgia. Furthermore, when the renal artery obstructs the proximal collecting system, filling defects can occur anywhere in the calyces, pelvis, or ureter.

Urine cytology is a test that looks for abnormal cells in urine under a microscope. The test commonly checks for infection, inflammatory disease of the urinary tract, cancer, or precancerous conditions. It can be part of a broader urinalysis. If a cancerous condition is detected, other tests and procedures are usually recommended to diagnose cancers, including bladder cancer, ureteral cancer and cancer of the urethra. It is especially recommended when blood in the urine (hematuria) has been detected.