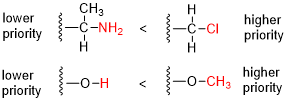

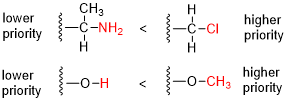

In organic chemistry, the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) sequence rules are a standard process to completely and unequivocally name a stereoisomer of a molecule. The purpose of the CIP system is to assign an R or S descriptor to each stereocenter and an E or Z descriptor to each double bond so that the configuration of the entire molecule can be specified uniquely by including the descriptors in its systematic name. A molecule may contain any number of stereocenters and any number of double bonds, and each usually gives rise to two possible isomers. A molecule with an integer n describing the number of stereocenters will usually have 2n stereoisomers, and 2n−1 diastereomers each having an associated pair of enantiomers. The CIP sequence rules contribute to the precise naming of every stereoisomer of every organic molecule with all atoms of ligancy of fewer than 4.

Cis–trans isomerism, also known as geometric isomerism, describes certain arrangements of atoms within molecules. The prefixes "cis" and "trans" are from Latin: "this side of" and "the other side of", respectively. In the context of chemistry, cis indicates that the functional groups (substituents) are on the same side of some plane, while trans conveys that they are on opposing (transverse) sides. Cis–trans isomers are stereoisomers, that is, pairs of molecules which have the same formula but whose functional groups are in different orientations in three-dimensional space. Cis and trans isomers occur both in organic molecules and in inorganic coordination complexes. Cis and trans descriptors are not used for cases of conformational isomerism where the two geometric forms easily interconvert, such as most open-chain single-bonded structures; instead, the terms "syn" and "anti" are used.

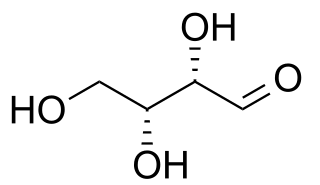

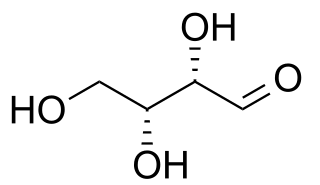

Monosaccharides, also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built. Simply, this is the structural unit of carbohydrates.

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. This contrasts with structural isomers, which share the same molecular formula, but the bond connections or their order differs. By definition, molecules that are stereoisomers of each other represent the same structural isomer.

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which by definition have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the geometric positioning of the atoms in space. For this reason, it is also known as 3D chemistry—the prefix "stereo-" means "three-dimensionality".

In chemistry, a racemic mixture or racemate, is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule or salt. Racemic mixtures are rare in nature, but many compounds are produced industrially as racemates.

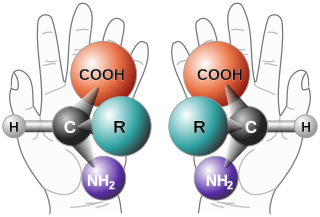

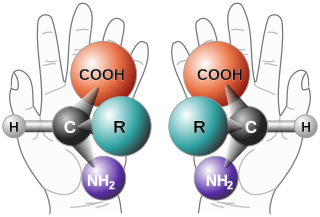

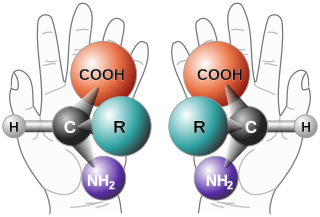

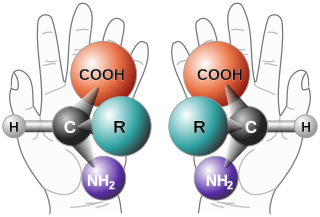

In chemistry, an enantiomer – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode – is one of two stereoisomers that are nonsuperposable onto their own mirror image. Enantiomers of each other are much like one's right and left hands; without mirroring one of them, hands cannot be superposed onto each other. It is solely a relationship of chirality and the permanent three-dimensional relationships among molecules or other chemical structures: no amount of re-orientiation of a molecule as a whole or conformational change converts one chemical into its enantiomer. Chemical structures with chirality rotate plane-polarized light. A mixture of equal amounts of each enantiomer, a racemic mixture or a racemate, does not rotate light.

In chemistry, racemization is a conversion, by heat or by chemical reaction, of an optically active compound into a racemic form. This creates a 1:1 molar ratio of enantiomers and is referred to as a racemic mixture. Plus and minus forms are called Dextrorotation and levorotation. The D and L enantiomers are present in equal quantities, the resulting sample is described as a racemic mixture or a racemate. Racemization can proceed through a number of different mechanisms, and it has particular significance in pharmacology as different enantiomers may have different pharmaceutical effects.

In stereochemistry, a stereocenter of a molecule is an atom (center), axis or plane that is the focus of stereoisomerism; that is, when having at least three different groups bound to the stereocenter, interchanging any two different groups creates a new stereoisomer. Stereocenters are also referred to as stereogenic centers.

In stereochemistry, diastereomers are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have different configurations at one or more of the equivalent (related) stereocenters and are not mirror images of each other. When two diastereoisomers differ from each other at only one stereocenter, they are epimers. Each stereocenter gives rise to two different configurations and thus typically increases the number of stereoisomers by a factor of two.

In organic chemistry, butyl is a four-carbon alkyl radical or substituent group with general chemical formula −C4H9, derived from either of the two isomers (n-butane and isobutane) of butane.

In chemistry, a molecule or ion is called chiral if it cannot be superposed on its mirror image by any combination of rotations, translations, and some conformational changes. This geometric property is called chirality. The terms are derived from Ancient Greek χείρ (cheir) 'hand'; which is the canonical example of an object with this property.

In chemistry, stereospecificity is the property of a reaction mechanism that leads to different stereoisomeric reaction products from different stereoisomeric reactants, or which operates on only one of the stereoisomers.

(E)-Stilbene, commonly known as trans-stilbene, is an organic compound represented by the condensed structural formula C6H5CH=CHC6H5. Classified as a diarylethene, it features a central ethylene moiety with one phenyl group substituent on each end of the carbon–carbon double bond. It has an (E) stereochemistry, meaning that the phenyl groups are located on opposite sides of the double bond, the opposite of its geometric isomer, cis-stilbene. Trans-stilbene occurs as a white crystalline solid at room temperature and is highly soluble in organic solvents. It can be converted to cis-stilbene photochemically, and further reacted to produce phenanthrene.

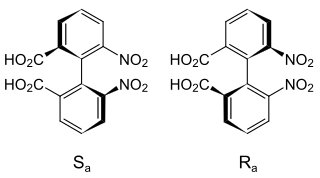

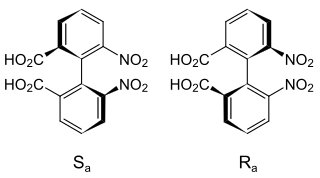

Atropisomers are stereoisomers arising because of hindered rotation about a single bond, where energy differences due to steric strain or other contributors create a barrier to rotation that is high enough to allow for isolation of individual conformers. They occur naturally and are important in pharmaceutical design. When the substituents are achiral, these conformers are enantiomers (atropoenantiomers), showing axial chirality; otherwise they are diastereomers (atropodiastereomers).

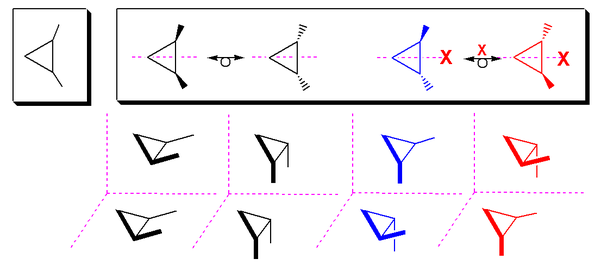

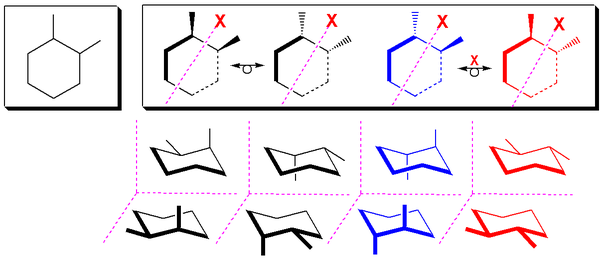

In organic chemistry, a ring flip is the interconversion of cyclic conformers that have equivalent ring shapes that results in the exchange of nonequivalent substituent positions. The overall process generally takes place over several steps, involving coupled rotations about several of the molecule's single bonds, in conjunction with minor deformations of bond angles. Most commonly, the term is used to refer to the interconversion of the two chair conformers of cyclohexane derivatives, which is specifically referred to as a chair flip, although other cycloalkanes and inorganic rings undergo similar processes.

1,2-Diphenyl-1,2-ethylenediamine, DPEN, is an organic compound with the formula H2NCHPhCHPhNH2, where Ph is phenyl (C6H5). DPEN exists as three stereoisomers: meso and two enantiomers S,S- and R,R-. The chiral diastereomers are used in asymmetric hydrogenation. Both diastereomers are bidentate ligands.

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Diamond and graphite are a familiar example; they are isomers of carbon. Isomerism refers to the existence or possibility of isomers.

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word chirality is derived from the Greek χείρ (kheir), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

In chemical nomenclature, a descriptor is a notational prefix placed before the systematic substance name, which describes the configuration or the stereochemistry of the molecule. Some of the listed descriptors should not be used in publications, as they no longer accurately correspond with the recommendations of the IUPAC. Stereodescriptors are often used in combination with locants to clearly identify a chemical structure unambiguously.