Cadmium is a chemical element; it has symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of its compounds, and like mercury, it has a lower melting point than the transition metals in groups 3 through 11. Cadmium and its congeners in group 12 are often not considered transition metals, in that they do not have partly filled d or f electron shells in the elemental or common oxidation states. The average concentration of cadmium in Earth's crust is between 0.1 and 0.5 parts per million (ppm). It was discovered in 1817 simultaneously by Stromeyer and Hermann, both in Germany, as an impurity in zinc carbonate.

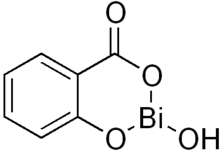

A toxic heavy metal is a common but misleading term for a metal noted for its potential toxicity. Not all heavy metals are toxic and some toxic metals are not heavy. Elements often discussed as toxic include cadmium, mercury and lead, all of which appear in the World Health Organization's list of 10 chemicals of major public concern. Other examples include chromium and nickel, thallium, bismuth, arsenic, antimony and tin.

Beryllium copper (BeCu), also known as copper beryllium (CuBe), beryllium bronze, and spring copper, is a copper alloy with 0.5–3% beryllium. Copper beryllium alloys are often used because of their high strength and good conductivity of both heat and electricity. It is used for its ductility, weldability in metalworking, and machining properties. It has many specialized applications in tools for hazardous environments, musical instruments, precision measurement devices, bullets, and some uses in the field of aerospace. Beryllium copper and other beryllium alloys are harmful carcinogens that present a toxic inhalation hazard during manufacturing.

A period 4 element is one of the chemical elements in the fourth row of the periodic table of the chemical elements. The periodic table is laid out in rows to illustrate recurring (periodic) trends in the chemical behaviour of the elements as their atomic number increases: a new row is begun when chemical behaviour begins to repeat, meaning that elements with similar behaviour fall into the same vertical columns. The fourth period contains 18 elements beginning with potassium and ending with krypton – one element for each of the eighteen groups. It sees the first appearance of d-block in the table.

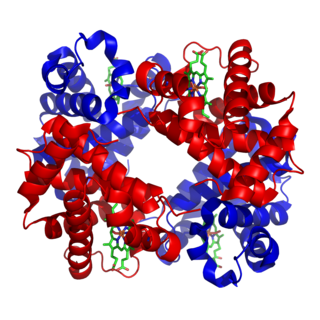

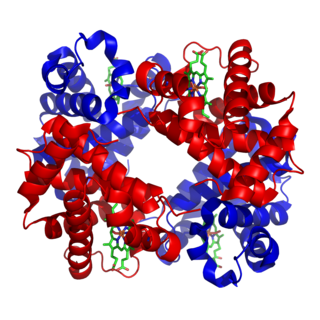

Metalloprotein is a generic term for a protein that contains a metal ion cofactor. A large proportion of all proteins are part of this category. For instance, at least 1000 human proteins contain zinc-binding protein domains although there may be up to 3000 human zinc metalloproteins.

A trace element is a chemical element of a minute quantity, a trace amount, especially used in referring to a micronutrient, but is also used to refer to minor elements in the composition of a rock, or other chemical substance.

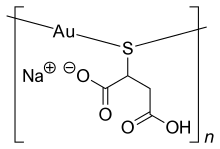

Metallothionein (MT) is a family of cysteine-rich, low molecular weight proteins. They are localized to the membrane of the Golgi apparatus. MTs have the capacity to bind both physiological and xenobiotic heavy metals through the thiol group of its cysteine residues, which represent nearly 30% of its constituent amino acid residues.

Group 12, by modern IUPAC numbering, is a group of chemical elements in the periodic table. It includes zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), and copernicium (Cn). Formerly this group was named IIB by CAS and old IUPAC system.

Dimercaprol, also called British anti-Lewisite (BAL), is a medication used to treat acute poisoning by arsenic, mercury, gold, and lead. It may also be used for antimony, thallium, or bismuth poisoning, although the evidence for those uses is not very strong. It is given by injection into a muscle.

Bioinorganic chemistry is a field that examines the role of metals in biology. Bioinorganic chemistry includes the study of both natural phenomena such as the behavior of metalloproteins as well as artificially introduced metals, including those that are non-essential, in medicine and toxicology. Many biological processes such as respiration depend upon molecules that fall within the realm of inorganic chemistry. The discipline also includes the study of inorganic models or mimics that imitate the behaviour of metalloproteins.

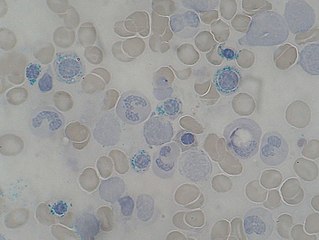

Cadmium is a naturally occurring toxic metal with common exposure in industrial workplaces, plant soils, and from smoking. Due to its low permissible exposure in humans, overexposure may occur even in situations where only trace quantities of cadmium are found. Cadmium is used extensively in electroplating, although the nature of the operation does not generally lead to overexposure. Cadmium is also found in some industrial paints and may represent a hazard when sprayed. Operations involving removal of cadmium paints by scraping or blasting may pose a significant hazard. The primary use of cadmium is in the manufacturing of NiCd rechargeable batteries. The primary source for cadmium is as a byproduct of refining zinc metal. Exposures to cadmium are addressed in specific standards for the general industry, shipyard employment, the construction industry, and the agricultural industry.

Biometals are metals normally present, in small but important and measurable amounts, in biology, biochemistry, and medicine. The metals copper, zinc, iron, and manganese are examples of metals that are essential for the normal functioning of most plants and the bodies of most animals, such as the human body. A few are present in relatively larger amounts, whereas most others are trace metals, present in smaller but important amounts. Approximately 2/3 of the existing periodic table is composed of metals with varying properties, accounting for the diverse ways in which metals have been utilized in nature and medicine.

Copper deficiency, or hypocupremia, is defined either as insufficient copper to meet the needs of the body, or as a serum copper level below the normal range. Symptoms may include fatigue, decreased red blood cells, early greying of the hair, and neurological problems presenting as numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, and ataxia. The neurodegenerative syndrome of copper deficiency has been recognized for some time in ruminant animals, in which it is commonly known as "swayback". Copper deficiency can manifest in parallel with vitamin B12 and other nutritional deficiencies.

Metal toxicity or metal poisoning is the toxic effect of certain metals in certain forms and doses on life. Some metals are toxic when they form poisonous soluble compounds. Certain metals have no biological role, i.e. are not essential minerals, or are toxic when in a certain form. In the case of lead, any measurable amount may have negative health effects. There is a popular misconception that only heavy metals can be toxic, but lighter metals such as beryllium and lithium can be toxic too. Not all heavy metals are particularly toxic, and some are essential, such as iron. The definition may also include trace elements when abnormally high doses may be toxic. An option for treatment of metal poisoning may be chelation therapy, a technique involving the administration of chelation agents to remove metals from the body.

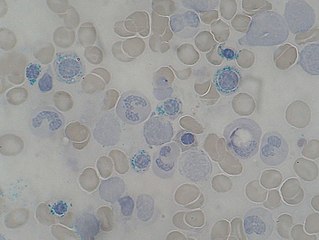

Zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) refers to coordination complexes of zinc and protoporphyrin IX. It is a red-purple solid that is soluble in water. The complex and related species are found in red blood cells when heme production is inhibited by lead and/or by lack of iron.

Copper toxicity is a type of metal poisoning caused by an excess of copper in the body. Copperiedus could occur from consuming excess copper salts, but most commonly it is the result of the genetic condition Wilson's disease and Menke's disease, which are associated with mismanaged transport and storage of copper ions. Copper is essential to human health as it is a component of many proteins. But hypercupremia can lead to copper toxicity if it persists and rises high enough.

Cobalt extraction refers to the techniques used to extract cobalt from its ores and other compound ores. Several methods exist for the separation of cobalt from copper and nickel. They depend on the concentration of cobalt and the exact composition of the ore used.

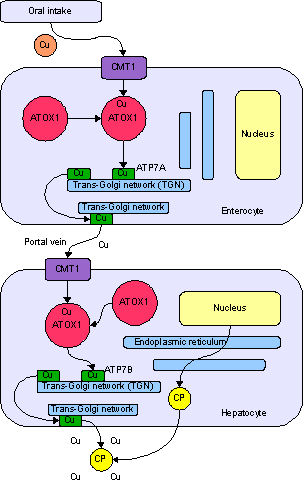

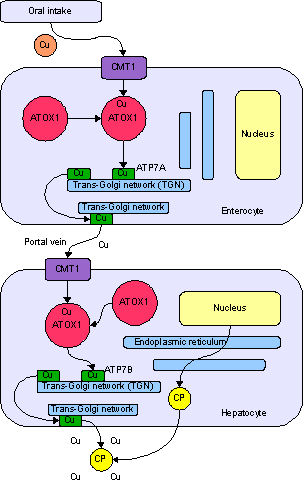

Copper is an essential trace element that is vital to the health of all living things. In humans, copper is essential to the proper functioning of organs and metabolic processes. Also, in humans, copper helps maintain the nervous system, immune system, brain development, and activates genes, as well as assisting in the production of connective tissues, blood vessels, and energy. The human body has complex homeostatic mechanisms which attempt to ensure a constant supply of available copper, while eliminating excess copper whenever this occurs. However, like all essential elements and nutrients, too much or too little nutritional ingestion of copper can result in a corresponding condition of copper excess or deficiency in the body, each of which has its own unique set of adverse health effects.

Heavy metals is a controversial and ambiguous term for metallic elements with relatively high densities, atomic weights, or atomic numbers. The criteria used, and whether metalloids are included, vary depending on the author and context and has been argued should not be used. A heavy metal may be defined on the basis of density, atomic number or chemical behaviour. More specific definitions have been published, none of which have been widely accepted. The definitions surveyed in this article encompass up to 96 out of the 118 known chemical elements; only mercury, lead and bismuth meet all of them. Despite this lack of agreement, the term is widely used in science. A density of more than 5 g/cm3 is sometimes quoted as a commonly used criterion and is used in the body of this article.