A meteorite is a rock that originated in outer space and has fallen to the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object enters the atmosphere, various factors such as friction, pressure, and chemical interactions with the atmospheric gases cause it to heat up and radiate energy. It then becomes a meteor and forms a fireball, also known as a shooting star; astronomers call the brightest examples "bolides". Once it settles on the larger body's surface, the meteor becomes a meteorite. Meteorites vary greatly in size. For geologists, a bolide is a meteorite large enough to create an impact crater.

A Martian meteorite is a rock that formed on Mars, was ejected from the planet by an impact event, and traversed interplanetary space before landing on Earth as a meteorite. As of September 2020, 277 meteorites had been classified as Martian, less than half a percent of the 72,000 meteorites that have been classified. The largest complete, uncut Martian meteorite, Taoudenni 002, was recovered in Mali in early 2021. It weighs 14.5 kilograms and is on display at the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum.

A metal detector is an instrument that detects the nearby presence of metal. Metal detectors are useful for finding metal objects on the surface, underground, and under water. A metal detector consists of a control box, an adjustable shaft, and a variable-shaped pickup coil. When the coil nears metal, the control box signals its presence with a tone, light, or needle movement. Signal intensity typically increases with proximity. A common type are stationary "walk through" metal detectors used at access points in prisons, courthouses, airports and psychiatric hospitals to detect concealed metal weapons on a person's body.

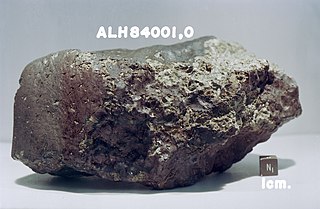

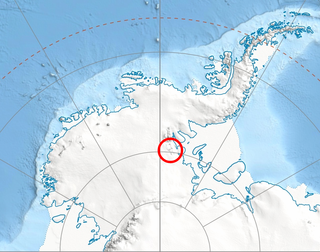

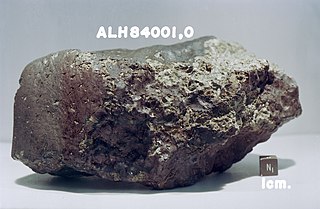

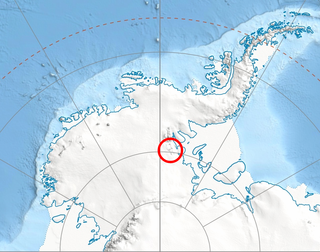

Allan Hills 84001 (ALH84001) is a fragment of a Martian meteorite that was found in the Allan Hills in Antarctica on December 27, 1984, by a team of American meteorite hunters from the ANSMET project. Like other members of the shergottite–nakhlite–chassignite (SNC) group of meteorites, ALH84001 is thought to have originated on Mars. However, it does not fit into any of the previously discovered SNC groups. Its mass upon discovery was 1.93 kilograms (4.3 lb).

A lunar meteorite is a meteorite that is known to have originated on the Moon. A meteorite hitting the Moon is normally classified as a transient lunar phenomenon.

The Morasko meteorite nature reserve is located in Morasko, on the northern edge of the city of Poznań, Poland. It contains seven meteor craters. The reserve has an area of 55 hectares and was established in 1976.

A micrometeorite is a micrometeoroid that has survived entry through the Earth's atmosphere. Usually found on Earth's surface, micrometeorites differ from meteorites in that they are smaller in size, more abundant, and different in composition. The IAU officially defines meteoroids as 30 micrometers to 1 meter; micrometeorites are the small end of the range (~submillimeter). They are a subset of cosmic dust, which also includes the smaller interplanetary dust particles (IDPs).

ANSMET is a program funded by the Office of Polar Programs of the National Science Foundation that looks for meteorites in the Transantarctic Mountains. This geographical area serves as a collection point for meteorites that have originally fallen on the extensive high-altitude ice fields throughout Antarctica. Such meteorites are quickly covered by subsequent snowfall and begin a centuries-long journey traveling "downhill" across the Antarctic continent while embedded in a vast sheet of flowing ice. Portions of such flowing ice can be halted by natural barriers such as the Transantarctic Mountains. Subsequent wind erosion of the motionless ice brings trapped meteorites back to the surface once more where they may be collected. This process concentrates meteorites in a few specific areas to much higher concentrations than they are normally found everywhere else. The contrast of the dark meteorites against the white snow, and lack of terrestrial rocks on the ice, makes such meteorites relatively easy to find. However, the vast majority of such ice-embedded meteorites eventually slide undiscovered into the ocean.

The pallasites are a class of stony–iron meteorite. They are relatively rare, and can be distinguished by the presence of large olivine crystal inclusions in the ferro-nickel matrix.

Treasure hunting is the physical search for treasure. For example, treasure hunters try to find sunken shipwrecks and retrieve artifacts with market value. This industry is generally fueled by the market for antiquities.

Antarctica is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest continent, being about 40% larger than Europe, and has an area of 14,200,000 km2 (5,500,000 sq mi). Most of Antarctica is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, with an average thickness of 1.9 km (1.2 mi).

Neuschwanstein was an enstatite chondrite meteorite that fell to Earth on 6 April 2002 at 22:20:18 GMT near Neuschwanstein Castle, Bavaria, at the Germany–Austria border.

Meteorite Men is a documentary reality television series featuring meteorite hunters Geoff Notkin and Steve Arnold. The pilot episode premiered on May 10, 2009. The full first season began on January 20, 2010, on the Science Channel. The second season premiered November 2, 2010, and season three began November 28, 2011. Professors and scientists at prominent universities including UCLA, ASU, UA, Edmonton, and other institutions, including NASA's Johnson Space Center, are featured.

The Sutter's Mill meteorite is a carbonaceous chondrite which entered the Earth's atmosphere and broke up at about 07:51 Pacific Time on April 22, 2012, with fragments landing in the United States. The name comes from Sutter's Mill, a California Gold Rush site, near which some pieces were recovered. Meteor astronomer Peter Jenniskens assigned Sutter's Mill (SM) numbers to each meteorite, with the documented find location preserving information about where a given meteorite was located in the impacting meteoroid. As of May 2014, 79 fragments had been publicly documented with a find location. The largest (SM53) weighs 205 grams (7.2 oz), and the second largest (SM50) weighs 42 grams (1.5 oz).

This is a glossary of terms used in meteoritics, the science of meteorites.

Patriot Hills is a line of rock hills 5 nautical miles (9 km) long, located 3 nautical miles (6 km) east of the north end of Independence Hills in Horseshoe Valley, Heritage Range, Western Antarctica.

The King Baudouin Ice Shelf in Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica, is within the Norwegian part of Antarctica. It is named after King Baudouin of Belgium (1930-1993).

Catherine Margaret Corrigan, often known as Cari Corrigan, is an American scientist best known as a curator of the meteorite collection at the Smithsonian Institution. She is a scientist in the Department of Mineral Science at the National Museum of Natural History.

A blue-ice area is an ice-covered area of Antarctica where wind-driven snow transport and sublimation result in net mass loss from the ice surface in the absence of melting, forming a blue surface that contrasts with the more common white Antarctic surface. Such blue-ice areas typically form when the movement of both air and ice are obstructed by topographic obstacles such as mountains that emerge from the ice sheet, generating particular climatic conditions where the net snow accumulation is exceeded by wind-driven sublimation and snow transports.

Katherine Helen Joy is a Professor in Earth Sciences at the University of Manchester. Joy has studied lunar samples from the Apollo program as part of her research on meteorites and lunar science.