A simulation is the imitation of the operation of a real-world process or system over time. Simulations require the use of models; the model represents the key characteristics or behaviors of the selected system or process, whereas the simulation represents the evolution of the model over time. Often, computers are used to execute the simulation.

America's Army is a series of first-person shooter video games developed and published by the U.S. Army, intended to inform, educate, and recruit prospective soldiers. Launched in 2002, the game was branded as a strategic communication device designed to allow Americans to virtually explore the Army at their own pace, and allowed them to determine whether becoming a soldier fits their interests and abilities. America's Army represents the first large-scale use of game technology by the U.S. government as a platform for strategic communication and recruitment, and the first use of game technology in support of U.S. Army recruiting.

A massively multiplayer online game is an online video game with a large numbers of players, often hundreds or thousands, on the same server. MMOs usually feature a huge, persistent open world, although there are games that differ. These games can be found for most network-capable platforms, including the personal computer, video game console, or smartphones and other mobile devices.

James H. Korris, a pioneer of the current trend in game-based simulation for military training, served as Creative Director of the Institute for Creative Technologies (Institute), University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles from its founding in August 1999 until October 2006. Dubbed "The Military Entertainment Complex", the modern collaboration of Hollywood and the Department of Defense at the institute was first discussed in a National Research Council study published in 1997. At the institute, Korris worked with talents as diverse as John Milius, Randal Kleiser and David Ayer The initial $44.5 million contract grew substantially as basic research in immersive virtual reality and prototype application development was expanded.

A military exercise or war game is the employment of military resources in training for military operations, either exploring the effects of warfare or testing strategies without actual combat. This also serves the purpose of ensuring the combat readiness of garrisoned or deployable forces prior to deployment from a home base. While both war games and military exercises aim to simulate real conditions and scenarios for the purpose of preparing and analyzing those scenarios, the distinction between a war game and a military exercise is determined, primarily, by the involvement of actual military forces within the simulation, or lack thereof. Military exercises focus on the simulation of real, full-scale military operations in controlled hostile conditions in attempts to reproduce war time decisions and activities for training purposes or to analyze the outcome of possible war time decisions. War games, however, can be much smaller than full-scale military operations, do not typically include the use of functional military equipment, and decisions and actions are carried out by artificial players to simulate possible decisions and actions within an artificial scenario which usually represents a model of a real-world scenario. Additionally, mathematical modeling is used in the simulation of war games to provide a quantifiable method of deduction. However, it is rare that a war game is depended upon for quantitative results, and the use of war games is more often found in situations where qualitative factors of the simulated scenario are needed to be determined.

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other forms of media, the OWI was the connection between the battlefront and civilian communities. The office also established several overseas branches, which launched a large-scale information and propaganda campaign abroad. From 1942 to 1945, the OWI revised or discarded any film scripts reviewed by them that portrayed the United States in a negative light, including anti-war material.

Mission to Moscow is a 1943 film directed by Michael Curtiz, based on the 1941 book by the former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph E. Davies.

The Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT) is a research institute of the University of Southern California located in Playa Vista, California. ICT was established in 1999 with funding from the US Army.

Virtual cinematography is the set of cinematographic techniques performed in a computer graphics environment. It includes a wide variety of subjects like photographing real objects, often with stereo or multi-camera setup, for the purpose of recreating them as three-dimensional objects and algorithms for the automated creation of real and simulated camera angles. Virtual cinematography can be used to shoot scenes from otherwise impossible camera angles, create the photography of animated films, and manipulate the appearance of computer-generated effects.Virtual cinematography is the set of cinematographic techniques performed in a computer graphics environment

Prelude to War is the first film of Frank Capra's Why We Fight film series commissioned by the Office of War Information (OWI) and George C. Marshall. It was made to educate American troops of the necessity of combating the Axis powers during World War II based on the idea that those in the service would fight more willingly and ably if they knew the background and the reason for their participation in the war. The film was later released to the general American public as a rallying cry for support of the war.

The Psychological Warfare Division of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force was a joint Anglo-American organization set-up in World War II tasked with conducting (predominantly) white tactical psychological warfare against German troops and recently liberated countries in Northwest Europe, during and after D-Day. It was headed by US Brigadier-General Robert A. McClure. The Division was formed from staff of the US Office of War Information (OWI) and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the British Political Warfare Executive (PWE).

SIMNET was a wide area network with vehicle simulators and displays for real-time distributed combat simulation: tanks, helicopters and airplanes in a virtual battlefield. SIMNET was developed for and used by the United States military. SIMNET development began in the mid-1980s, was fielded starting in 1987, and was used for training until successor programs came online well into the 1990s.

Irregular warfare (IW) is defined in United States joint doctrine as "a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant populations." Concepts associated with irregular warfare are older than the term itself.

At various times, under its own initiative or in accordance with directives from the President of the United States or the National Security Council staff, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has attempted to influence public opinion both in the United States and abroad.

A serious game or applied game is a game designed for a primary purpose other than pure entertainment. The "serious" adjective is generally prepended to refer to video games used by industries like defense, education, scientific exploration, health care, emergency management, city planning, engineering, and politics. Serious games are a subgenre of serious storytelling, where storytelling is applied "outside the context of entertainment, where the narration progresses as a sequence of patterns impressive in quality ... and is part of a thoughtful progress". The idea shares aspects with simulation generally, including flight simulation and medical simulation, but explicitly emphasizes the added pedagogical value of fun and competition.

Morale Operations was a branch of the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. It utilized psychological warfare, particularly propaganda, to produce specific psychological reactions in both the general population and military forces of the Axis powers in support of larger Allied political and military objectives.

During World War II, the entertainment industry changed to help the war effort. Often the industry became more closely controlled by national governments, who believed that a supportive home front was crucial to victory. Through regulation and censorship, governments sought to keep spirits high and to depict the war in a positive light. They also found new ways to use entertainment media to keep citizens informed.

Zero Dark Thirty is a 2012 American thriller film directed by Kathryn Bigelow and written by Mark Boal. The film dramatizes the nearly decade-long international manhunt for Osama bin Laden, leader of terrorist network Al-Qaeda, after the September 11 attacks. This search leads to the discovery of his compound in Pakistan and the military raid where bin Laden was killed on May 2, 2011.

Propaganda is information that is not impartial and used primarily to influence an audience and further an agenda, often by presenting facts selectively to encourage a particular synthesis, or using loaded messages to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information presented. The term propaganda has acquired a strongly negative connotation by association with its most manipulative and jingoistic examples.

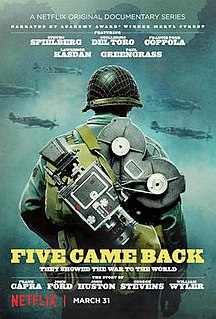

Five Came Back is an American documentary based on the 2014 book Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War by journalist Mark Harris. It was released as a stand-alone documentary in New York and Los Angeles, and as a three-part series on Netflix, on March 31, 2017.