The Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem has four minarets in total: three on the western flank and one on the northern flank.

The Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem has four minarets in total: three on the western flank and one on the northern flank.

Early Muslim writer Shihab Al-Din Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Ibn 'Abd Rabbihi (d. 940 AD), in his Kitab Al-Iqd Al-Farid, describe the pre-Crusader Al-Aqsa enclave as having four minarets. [1]

After they conquered Jerusalem,[ clarification needed ] defeating the Crusaders, the Mamluks built or renovated eight major minarets in the Holy City. [2] Dating of the minarets in Jerusalem has been done according to the style and shape. Mamluk minarets generally have a square shape [3] and are built at various locations along the perimeter of the Haram al-Sharif.

The Ghawanima Minaret or Al-Ghawanima Minaret was built at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary during the reign of Sultan Lajin circa 1298, or between 1297 and 1299, [4] or circa circa 1298. [5] [6] It is named after Shaykh Ghanim ibn Ali ibn Husayn, who was appointed the Shaykh of the Salahiyyah Madrasah by Saladin. [7] [ unreliable source ]

The minaret is located near the Ghawanima Gate and is the most decorated minaret of the compound. [8] It is 38.5 meters tall, with six stories and an internal staircase of 120 steps, making it the highest minaret inside the Al-Aqsa compound. [8] [9] Its design may have been influenced by the Romanesque style of older Crusader buildings in the city. [6]

The tower's main shaft is cuboid, with a square base, while its upper part, above the balcony, is octagonal. It is almost entirely made of stone, apart from a timber canopy over the muezzin's balcony. Marble columns are employed in its decoration. [10] The minaret is excavated into the naturally occurring layer of bedrock in the northwest corner of the Haram. The main part of the tower has a cuboid shape with a square base. It is partitioned into several 'stories', visually divided on the outside by stone moldings and muqarnas (stalactite) cornices. The first two stories are wider and form the base of the tower, followed by an additional four stories, including the muezzin's gallery or balcony. Above the level of the balcony is a smaller octagonal turret surmounted by a bulbous dome with a circular drum. The stairway is external on the first two floors but becomes an internal spiral structure until it reaches the muezzin's gallery, from which the call for prayer was performed. [10] [11]

The western tunnel, which was dug by the Israeli state, has weakened the minaret's foundations, resulting in calls for its renovation in 2001. [12] Also, the Islamic Waqf Directorate has renovated this gate after an Israeli extremist burnt it in 1998. [8]

In 1329, Tankiz, the Mamluk governor of Syria, ordered the construction of a third minaret, known as the Bab al-Silsila Minaret (Minaret of the Chain Gate), near the Chain Gate, on the western border of the al-Aqsa Mosque. [13] [11] The minaret is also known as Mahkamah Minaret since the minaret is located near the Madrasa al-Tankiziyya which served as a law court during the times of Ottomans. [14]

This minaret, possibly replacing an earlier Umayyad minaret, is built in the traditional Syrian square tower type and is made entirely out of stone. [15]

Since the 16th century, it has been a tradition that the best muezzin of the adhan (the call to prayer) is assigned to this minaret because the first call to each of the five daily prayers is raised from it, giving the signal for the muezzins of mosques throughout Jerusalem to follow suit. [16] [ full citation needed ]

It is located next to the Chain Gate on the porches to the west of Masjid al-Aqsa. It is on a square-shaped platform with four corners and has a closed balcony, which is kept standing by stone columns. It has an internal staircase with 80 steps. [8] The minaret is reached via the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya. The height of the minaret is 35 meters.[ citation needed ] It was repaired by the Islamic Foundation after the Jerusalem earthquake in 1922. [8] [ additional citation(s) needed ]

Bab al-Silsila Minaret is bordered by Al Aqsa Compound's main entrance. As stated in the inscriptions, its reconstruction was done by the Governor of Syria when Amir Tankiz was establishing the Madrasa al-Tankiziyya. It was replaced by an Ottoman-style 'pencil point' spire, which was replaced by a smooth cutout and a semicircular dome after the dome was damaged in an earthquake in the 19th century. During the restoration of 1923-4, the existing canopy and lead coating on the dome were erected. [17] [18]

Today, Israeli security forces do not allow Muslims to approach or enter Bab al-Silsila Minaret, as they believe they protect praying Jews in front of the Western Wall which is near Bab al-Silsila Minaret. [8]

The Fakhriyya Minaret [19] [20] or Al-Fakhiriyya Minaret, [21] was built on the junction of the southern wall and western wall, [22] over the solid part of the wall. [23] The exact date of its original construction is not known but it was built sometime after 1345 and before 1496. [19] [24] It was named after Fakhr al-Din al-Khalili, the father of Sharif al-Din Abd al-Rahman who supervised the building's construction.[ citation needed ] The minaret was rebuilt in 1920. [25] [ verification needed ][ full citation needed ]

The Fakhriyya Minaret was built in the traditional Syrian style, with a square-shaped base and shaft, divided by moldings into three floors above which two lines of muqarnas decorate the muezzin's balcony. The niche is surrounded by a square chamber that ends in a lead-covered stone dome. [26] [ full citation needed ] After the minaret was damaged in the Jerusalem earthquake, the minaret's dome was covered with lead. [25]

The last and most notable minaret was built in 1367: the Bāb al-ʾAsbāṭ Minaret, near the Tribes' Gate (al-ʾAsbāṭ Gate). It is composed of a cylindrical stone shaft (built later by the Ottomans), which springs up from a rectangular Mamluk-built base on top of a triangular transition zone. [27] The shaft narrows above the muezzin's balcony and is dotted with circular windows, ending with a bulbous dome. The dome was reconstructed after the 1927 earthquake. [27]

There are no minarets in the eastern portion of the mosque. However, in 2006, King Abdullah II of Jordan announced his intention to build a fifth minaret overlooking the Mount of Olives. The King Hussein Minaret is planned to be the tallest structure in the Old City of Jerusalem. [28] [29]

The Temple Mount, also known as The Noble Sanctuary, al-Aqsa Mosque compound, or simply al-Aqsa, and sometimes as Jerusalem's holyesplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a holy site for thousands of years, including in Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

The Aqsa Mosque, also known as the Qibli Mosque or Qibli Chapel, is the main congregational mosque or prayer hall in the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem. In some sources the building is also named al-Masjid al-Aqṣā, but this name primarily applies to the whole compound in which the building sits, which is itself also known as "Al-Aqsa Mosque". The wider compound is known as Al-Aqsa or Al-Aqsa mosque compound, also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf.

The Temple Mount, a holy site in the Old City of Jerusalem, also known as the al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf or Al-Aqsa, contains twelve gates. One of the gates, Bab as-Sarai, is currently closed to the public but was open under Ottoman rule. There are also six other sealed gates. This does not include the Gates of the Old City of Jerusalem which circumscribe the external walls except on the east side.

Dome of the Chain is an Islamic free-standing domed building located adjacently east of the Dome of the Rock in the al-Aqsa Mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is one of many small buildings that can be found scattered around the Al Aqsa Mosque. Its exact historical use and significance are under scholarly debate. Erected in 691–92 CE, the Dome of the Chain is one of the oldest surviving structures at the al-Aqsa Mosque compound.

The Fountain of Qasim Pasha is an ablution and drinking fountain in the western esplanade of the al-Aqsa Compound in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is in front of the Chain Gate.

The Islamic Museum is a museum at Al Aqsa in the Old City section of Jerusalem. On display are exhibits from ten periods of Islamic history encompassing several Muslim regions. The museum is west of al-Aqsa Mosque, across a courtyard.

Fountain of Qayt Bay or Sabil Qaitbay is a domed public fountain (sabil) on the western esplanade of the al-Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, near the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya. Built in the 15th century by the Mamluks of Egypt, it was completed in the reign of Sultan Qaytbay, after whom it is named. It is also colloquially known as the Fountain of Hamidiye due to Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s restoration. It has been considered, "after the Dome of the Rock, the most beautiful edifice in the Haram".

The al-Buraq Mosque is a subterranean musalla next to the Buraq Wall, near the southwest corner of the Masjid al-Aqsa compound in the Old City of Jerusalem. This mosque is called al-Buraq Mosque because of a ring that is nailed to its wall where Muslims believe Muhammad tied the Buraq that carried him from the al-Haram Mosque to the al-Aqsa Mosque during the Night Journey.

Bab Al-Asbat Minaret, Minaret of the Tribes, is a minaret in Jerusalem. The other name is the Minaret of Salahiyah which refers to the Salahiyah School close to it. It is one of the four minarets of Al-Aqsa, and is situated along the north wall.

Bāb Ḥuṭṭa is a neighborhood in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem to the north of Al-Aqsa Compound. The name literally means "Forgiveness Gate", referring to the Remission Gate of the Haram compound, connected by Bāb Ḥuṭṭa Street.

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style that developed under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were prolific patrons of architecture and contributed enormously to the fabric of historic Cairo. The Mamluk period, particularly in the 14th century, oversaw the peak of Cairo's power and prosperity. Their architecture also appears in cities such as Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Tripoli, and Medina.

The Madrasaal-Ashrafiyya is an Islamic madrasa structure built in 1480–1482 by the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay on the western side of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem. Although only a part of the original structure still stands today, it is a notable example of royal Mamluk architecture in Jerusalem.

The Inspector's Gate is one of the gates of the al-Aqsa Compound. It is the second-northernmost gates in the compound's west wall, after the Bani Ghanim Gate. It is north of the Iron Gate.

The Cotton Merchants' Gate is one of the gates of the al-Aqsa Compound. It is by the western esplanade of the compound and leads to the Cotton Merchants' Market, a sūq, it is also called the Gate of the Cotton Merchants' Market. Its intricate eastern façade makes it one of the most recognizable and "the grandest of the Haram gates".

The Gate of the Chain or Chain Gate is one half of a double gate, part of the gates to the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. It was known early Islamic period Bāb Daud, which means David's Gate. It was also known as Bāb al-Maḥkama, Gate of the Law Court, named after the nearby Maḥkama in the Tankiziyya building.

The Dome of Yusuf Agha is a small square building with a dome in the al-Aqsa Compound, in the courtyard between the Islamic Museum and al-Aqsa Mosque (al-Qibli).

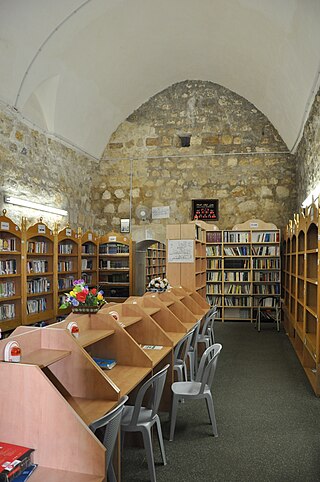

The al-Aqsa Library, also known as the al-Aqsa Mosque Library, is the assemblage of books in the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in Jerusalem.

The at-Tankiziyya is a historic building in Jerusalem that included a madrasa. It is part of the west wall of the al-Aqsa Compound. It is also known as the Maḥkama building.

Al-Aqsa or al-Masjid al-Aqṣā is the compound of Islamic religious buildings that sit atop the Temple Mount, also known as the Haram al-Sharif, in the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock, many mosques and prayer halls, madrasas, zawiyas, khalwas and other domes and religious structures, as well as the four encircling minarets. It is considered the third holiest site in Islam. The compound's main congregational mosque or prayer hall is variously known as Al-Aqsa Mosque, Qibli Mosque or al-Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā, while in some sources it is also known as al-Masjid al-Aqṣā; the wider compound is sometimes known as Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in order to avoid confusion.