Operations

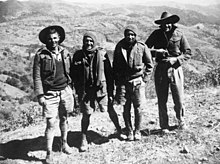

In addition to the Australians who had two officers and 43 men, 'Tulip Force' also consisted of a number of British troops. In total, Mission 204 was composed of six commando contingents, three of which were deployed to China. (Of the other three, one was disbanded because of ill discipline, and the other two were involved in other missions against the Japanese.) The aim of the Mission was to infiltrate into China, and train Chinese guerrillas to fight the Japanese. [4]

First phase

The men departed in February 1942, the first Phase consisting of three Contingents, two British and one Australian, each of 50 army commandos. [4] They travelled up the Burma Road in trucks for nearly three weeks before crossing into China, covering more than 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi). From there they travelled another 800 kilometres (500 mi) by train into China, before traversing the mountainous border region to join Lieutenant-Colonel Chen Ling Sun's Chinese 5th Battalion. They brought with them large amounts of equipment, including explosives.

The Australian Minister in Chongqing, Sir Frederic Eggleston, visited the men in their camp at Kiyang at the end of May, later recommending that the troops remain at their base.

Mission 204 troops lived in the mountains with the Chinese Surprise Troops (so called because of their ability to surprise the enemy. The Nationalists did not like the term Guerrilla because it was associated with communists). However, due to the nature of combat, the surprise was not a positive one (like the giving of a gift), it was normally a surprise that involved an assault or military action [5] There were communications issues between the unit and the Chinese. Mission 204 had no food, as they had understood that the Chinese would provide it. The Chinese themselves had no food, but foraged for it and took what they wanted from the peasants, expecting that naturally the British nd Australians would do the same. Despite the problems, the men trained the Chinese Surprise troops in using weapons, demolitions and ambush techniques. [4] The also helped to rescue allied POWs most of whom had made the long trek after having escaped the Japanese after the fall of Hong Kong - one even joined Mission 204, while the others were helped back to India. [6]

204 Mission, however were forbidden by the Chinese to take part in any of their guerrilla actions. [4] The unit did undertake some operations, but without Chinese support, and with the latter advising against it. These included a number of successful ambushes against various Japanese patrols, and an assault on a blockhouse which saw its destruction. [7] The biggest operation however was a raid which took place on a river near Poyang lake in the Nanchang area. A bridge and river barges linked to a nearby Japanese airfield were targeted. Members of the unit in the dark managed to attach limpet mines to a number of Japanese ammunition barges, destroying them and the bridge. It was the high point of Mission 204 in 1942. In these actions none of the unit were killed in combat although some were wounded. [8]

A further visit by Eggleston was made to the unit in September. Following this it was decided they should be pulled out. There were a number of issues of concern, firstly and foremost, sickness was rife within the unit; Eggelstone was appalled at their conditions. The men had been suffering from dysentery, malaria, typhus and other diseases - two died as a result. There were also political considerations especially between the communists and Nationalists, both accused the unit of having supported one another. In addition, despite the success they achieved on their own, the soldiers had no confidence in their Chinese commander, and it was perceived that they were not being used to any benefit by the Chinese military. [9] There were also concerns in high command that the unit was becoming a sort of private army. [10]

The unit withdrew towards Kunming airfield which was the headquarters of the American Volunteer group, 'Flying Tigers'. After resting and recuperating there, the unit was flown out by the Americans in November 1942 to India. Some of the unit would later train troops for the Burma campaign. The Australian contingent arrived home and were greeted as heroes. [11]

Second Phase

Despite the withdrawal of the unit, an attempt was made to reform it, with lessons learned from the unsuccessful first phase. This time, to overcome the issues with disease, medical and ration supplies would to be flown in. Better communications and relations with the Chinese was also to be established, the politics were ironed out – the unit would only work with the Nationalists and this time they were to fight with the Chinese as well as train them.

The unit was flown in to Kumning airfield in February 1943 and operated under standard British Military command, as opposed to the first phase which operated under the SOE. British medical and demolition experts were assigned to the Chinese Surprise troops, and this time valid assistance was also given to the guerrillas in various actions against the Japanese. These involved ambushes, attacks on airfields, blockhouses, positions and supply depots. Communications with command was also better established and also counted on American air support from the 'Flying Tigers'. [5]

However, with the major Japanese Operation Ichi-Go underway, the Mission 204 soldiers were pulled out of China, being flown out of the area by the USAAF whose bases at Guilin and Luizhou were the targets of the Japanese. [5]