Related Research Articles

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or a family of religions which is influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Africa and the Near East. Although they share similarities, contemporary pagan movements are diverse and as a result, they do not share a single set of beliefs, practices, or texts. Scholars of religion often characterise these traditions as new religious movements. Some academics who study the phenomenon treat it as a movement that is divided into different religions while others characterize it as a single religion of which different pagan faiths are denominations.

Wicca, also known as The Craft, is a modern neo-pagan syncretic religion. Scholars of religion categorize it as both a new religious movement and as part of occultist Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was introduced to the public in 1954 by Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant. Wicca draws upon a diverse set of ancient pagan and 20th-century hermetic motifs for its theological structure and ritual practices.

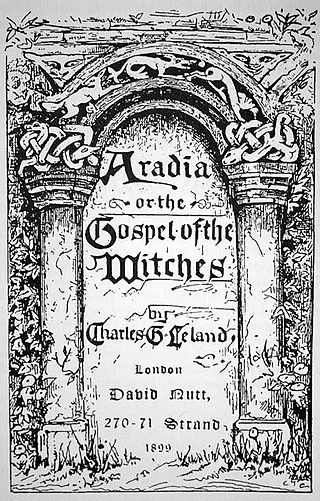

Aradia is one of the principal figures in the American folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland's 1899 work Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, which he believed to be a genuine religious text used by a group of pagan witches in Tuscany, a claim that has subsequently been disputed by other folklorists and historians. In Leland's Gospel, Aradia is portrayed as a messiah who was sent to Earth in order to teach the oppressed peasants how to perform witchcraft to use against the Roman Catholic Church and the upper classes.

Stregheria is a neo-pagan tradition similar to Wicca, with Italian and Italian American origins. While most practitioners consider Stregheria to be a distinct tradition from Wicca, some academics consider it to be a form of Wicca or an offshoot. Both have similar beliefs and practices. For example, Stregheria honors a pantheon centered on a Moon Goddess and a Horned God, similar to Wiccan views of divinity.

Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today is a sociological study of contemporary Paganism in the United States written by the American Wiccan and journalist Margot Adler. First published in 1979 by Viking Press, it was later republished in a revised and expanded edition by Beacon Press in 1986, with third and fourth revised editions being brought out by Penguin Books in 1996 and then 2006 respectively.

Celtic Wicca is a modern form of Wicca that incorporates some elements of Celtic mythology. It employs the same basic theology, rituals and beliefs as most other forms of Wicca. Celtic Wiccans use the names of Celtic deities, mythological figures, and seasonal festivals within a Wiccan ritual structure and belief system, rather than a traditional or historically Celtic one.

Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches is a book composed by the American folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland that was published in 1899. It contains what he believed was the religious text of a group of pagan witches in Tuscany, Italy that documented their beliefs and rituals, although various historians and folklorists have disputed the existence of such a group. In the 20th century, the book was very influential in the development of the contemporary Pagan religion of Wicca.

Celtic modern paganism refers to any type of modern paganism or contemporary pagan movements based on the ancient Celtic religion.

Phyllis Curott who goes under the craft name Aradia, is a Wiccan priestess, attorney, and author.

The history of Wicca documents the rise of the Neopagan religion of Wicca and related witchcraft-based Neopagan religions. Wicca originated in the early 20th century, when it developed amongst secretive covens in England who were basing their religious beliefs and practices upon what they read of the historical witch-cult in the works of such writers as Margaret Murray. It also is based on the beliefs from the magic that Gerald Gardner saw when he was in India. It was subsequently founded in the 1950s by Gardner, who claimed to have been initiated into the Craft – as Wicca is often known – by the New Forest coven in 1939. Gardner's form of Wicca, the Gardnerian tradition, was spread by both him and his followers like the High Priestesses Doreen Valiente, Patricia Crowther and Eleanor Bone into other parts of the British Isles, and also into other, predominantly English-speaking, countries across the world. In the 1960s, new figures arose in Britain who popularized their own forms of the religion, including Robert Cochrane, Sybil Leek and Alex Sanders, and organizations began to be formed to propagate it, such as the Witchcraft Research Association. It was during this decade that the faith was transported to the United States, where it was further adapted into new traditions such as Feri, 1734 and Dianic Wicca in the ensuing decades, and where organizations such as the Covenant of the Goddess were formed.

Wiccan views of divinity are generally theistic, and revolve around a Goddess and a Horned God, thereby being generally dualistic. In traditional Wicca, as expressed in the writings of Gerald Gardner and Doreen Valiente, the emphasis is on the theme of divine gender polarity, and the God and Goddess are regarded as equal and opposite divine cosmic forces. In some newer forms of Wicca, such as feminist or Dianic Wicca, the Goddess is given primacy or even exclusivity. In some forms of traditional witchcraft that share a similar duotheistic theology, the Horned God is given precedence over the Goddess.

Modern paganism in the United States is represented by widely different movements and organizations. The largest modern pagan religious movement is Wicca, followed by Neodruidism. Both of these religions or spiritual paths were introduced during the 1950s and 1960s from Great Britain. Germanic Neopaganism and Kemetism appeared in the US in the early 1970s. Hellenic Neopaganism appeared in the 1990s.

Neopagan witchcraft, sometimes referred to as The Craft, is an umbrella term for some neo-pagan traditions that include the attempted practice of magic. These traditions began in the mid-20th century and were influenced by the witch-cult hypothesis, a now-rejected theory that persecuted witches in Europe had actually been followers of a surviving pagan religion. Traditions classed as neopagan witchcraft include Wicca and the various movements that describe themselves as "Traditional Witchcraft".

Neopaganism in Hungary is very diverse, with followers of the Hungarian Native Faith and of other religions, including Wiccans, Kemetics, Mithraics, Druids and Christopagans.

A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-Paganism and Witchcraft in the United States is a sociological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the Northeastern United States. It was written by American sociologist Helen A. Berger of the West Chester University of Pennsylvania and first published in 1999 by the University of South Carolina Press. It was released as a part of a series of academic books entitled Studies in Comparative Religion, edited by Frederick M. Denny, a religious studies scholar at the University of Chicago.

Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives is an academic anthology edited by the American religious studies scholar Michael F. Strmiska which was published by ABC-CLIO in 2005. Containing eight separate papers produced by various scholars working in the field of Pagan studies, the book examines different forms of contemporary Paganism as practiced in Europe and North America. Modern Paganism in World Cultures was published as a part of ABC-CLIO's series of books entitled 'Religion in Contemporary Cultures', in which other volumes were dedicated to religious movements like Buddhism and Islam.

Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco is an anthropological study of the Reclaiming Wiccan community of San Francisco. It was written by the Scandinavian theologian Jone Salomonsen of the California State University, Northridge and first published in 2002 by the Routledge.

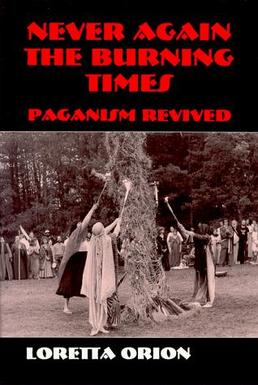

Never Again the Burning Times: Paganism Revisited is an anthropological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the United States. It was written by the American anthropologist Loretta Orion and published by Waveland Press in 1995.

Modern paganviews on LGBT people vary considerably among different paths, sects, and belief systems. LGBT individuals comprise a much larger percentage of the population in neopagan circles than larger, mainstream religious populations. There are some popular neopagan traditions which have beliefs often in conflict with the LGBT community, and there are also traditions accepting of, created by, or led by LGBT individuals. The majority of conflicts concern heteronormativity and cisnormativity.

References

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_225_report_en.pdf [ bare URL PDF ]

- ↑ http://www.lapf.eu/faq.php Libre Assemblée Païenne Francophone, Frequently Asked Questions (French)

- ↑ "Templi E Santuari". Tradizione Romana. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ "Temple of Jupiter in Torre Gaia". Pagan Places. 13 February 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ "Tempio della Grande Dea". Pagan Places. 19 May 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ Cardinal Lopez Trujillo warns of risk of neo-paganism in Spain [ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "Entrevista a Fernando González del Consejo Wiccano Wicca Celtíbera". 14 January 2012.

- ↑ "asatru.es". Archived from the original on 2015-10-24. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "OTRAS RELIGIONES / Discípulos de Odín en Albacete. La Verdad". Archived from the original on 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2013-12-06. "La verdad" daily

- ↑ "Wicca Celtíbera registrada como confesión también en Portugal | PNC Spain". Archived from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- Ethnologie française, numéro 4 - 2000 : Les nouveaux mouvements religieux (2001), ISBN 978-2-13-050694-2.

- Francesco Faraoni, Il Neopaganesimo, Aradia Edizioni (2006), ISBN 978-88-901500-3-6.

- Cronos, Wicca - la nuova era della Vecchia Religione, Aradia Edizioni (2007), ISBN 88-901500-6-8.