Zionist political violence refers to acts of violence or terrorism committed by Zionists in support of establishing and maintaining a Jewish state in Palestine. These actions have been carried out by individuals, paramilitary groups, and the Israeli government, from the early 20th century to the present day, as part of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Zionism is an ethnic or ethno-cultural nationalist movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed for the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people through the colonization of the region of Palestine, a region corresponding to the Land of Israel in Jewish tradition, an area with deep historical, national and religious importance in Jewish identity, history and religion. Following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism became an ideology that supports the development and protection of Israel as a Jewish state. It has also been described as Israel's national or state ideology.

David Ben-Gurion was the primary national founder of the State of Israel as well as its first prime minister. As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, and later president of the Jewish Agency Executive, he was the de facto leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, and largely led the movement for an independent Jewish state in Mandatory Palestine.

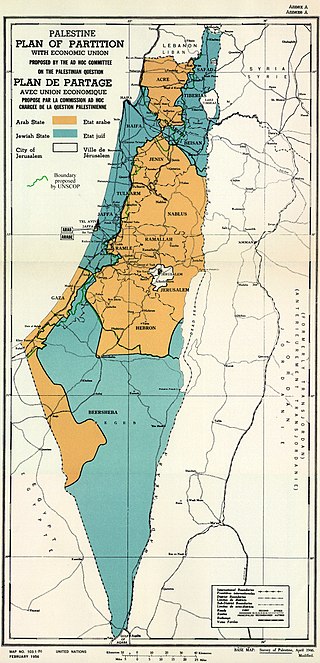

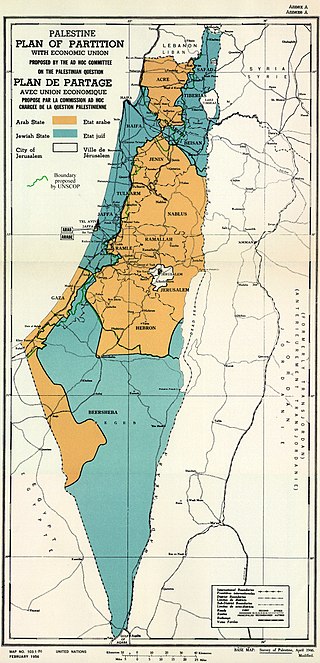

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Resolution 181 (II). The resolution recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish States linked economically and a Special International Regime for the city of Jerusalem and its surroundings.

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction of the First Temple and the Babylonian exile.

The Churchill White Paper of 3 June 1922 was drafted at the request of Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, partly in response to the 1921 Jaffa Riots. The official name of the document was Palestine: Correspondence with the Palestine Arab Delegation and the Zionist Organisation. The white paper was made up of nine documents and "Churchill's memorandum" was an enclosure to document number 5. While maintaining Britain's commitment to the Balfour Declaration and its promise of a Jewish national home in Mandatory Palestine, the paper emphasized that the establishment of a national home would not impose a Jewish nationality on the Arab inhabitants of Palestine. To reduce tensions between the Arabs and Jews in Palestine the paper called for a limitation of Jewish immigration to the economic capacity of the country to absorb new arrivals. This limitation was considered a great setback to many in the Zionist movement, though it acknowledged that the Jews should be able to increase their numbers through immigration rather than sufferance.

Ernest Bevin was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He cofounded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and served as Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government. He succeeded in maximising the British labour supply for both the armed services and domestic industrial production with a minimum of strikes and disruption.

Yishuv, HaYishuv HaIvri, or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el denotes the body of Jewish residents in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 25,000 Jews living in that region, and continued to be used until 1948, by which time there were some 630,000 Jews there. The term is still in use to denote the pre-1948 Jewish residents in Palestine, corresponding to the southern part of Ottoman Syria until 1918, OETA South in 1917–1920, and Mandatory Palestine in 1920–1948.

The White Paper of 1939 was a policy paper issued by the British government, led by Neville Chamberlain, in response to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. After its formal approval in the House of Commons on 23 May 1939, it acted as the governing policy for Mandatory Palestine from 1939 to the 1948 British departure. After the war, the Mandate was referred to the United Nations.

Nahum Goldmann was a leading Zionist. He was a founder of the World Jewish Congress and its president from 1951 to 1978, and was also president of the World Zionist Organization from 1956 to 1968.

The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American committee assembled in Washington, D.C., on 4 January 1946. The committee was tasked to examine political, economic and social conditions in Mandatory Palestine and the well-being of the peoples now living there; to consult representatives of Arabs and Jews, and to make other recommendations 'as may be necessary' to for ad interim handling of these problems as well as for their permanent solution. The report, entitled "Report of the Anglo-American Committee of Enquiry Regarding the Problems of European Jewry and Palestine", was published in Lausanne on 20 April 1946.

Henry Francis Grady was an American economist, businessman and diplomat. He was a dean at the University of California, and a business executive. He became the first US Ambassador to India, followed by Ambassador to Greece, and Ambassador to Iran (1950–1951). He was against British colonialism in India and Iran. He worked with British diplomats in 1946 to devise a plan for continued British control of Palestine, but the Morrison–Grady Plan was rejected by both Arabs and Jews.

A successful paramilitary campaign, sometimes referred to as the Palestine Emergency, was carried out by Zionist underground groups against British rule in Mandatory Palestine from 1944 to 1948. The tensions between the Zionist underground and the British mandatory authorities rose from 1938 and intensified with the publication of the White Paper of 1939. The Paper outlined new government policies to place further restrictions on Jewish immigration and land purchases, and declared the intention of giving independence to Palestine, with an Arab majority, within ten years. Though World War II brought relative calm, tensions again escalated into an armed struggle towards the end of the war, when it became clear that the Axis powers were close to defeat.

Ihud was a small binationalist Zionist political party founded by Judah Leon Magnes, Martin Buber, Ernst Simon and Henrietta Szold, former supporters of Brit Shalom, in 1942 as a binational response to the Biltmore Conference, which made the establishment of a Jewish Commonwealth in Palestine the policy of the Zionist movement. Other prominent members were David Werner Senator, Moshe Smilansky, agronomist Haim Margaliot-Kalvarisky (1868–1947), and Judge Joseph Moshe Valero.

Mandatory Palestine was a geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the region of Palestine under the terms of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine.

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the State of Israel, and over 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled. It was the first war of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the broader Arab–Israeli conflict.

The London Conference of 1946–1947, which took place between September 1946 and February 1947, was called by the British Government of Clement Attlee to resolve the future governance of Palestine and negotiate an end of the Mandate. It was scheduled following an Arab request after the April 1946 Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry report.

The Harrison Report was a July 1945 report carried out by United States lawyer Earl G. Harrison, as U.S. representative to the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, into the conditions of the displaced persons camps in post-World War II Europe.

The Bevin Plan, also described as the Bevin–Beeley Plan was Britain's final attempt in the mid-20th century to solve the troubled situation that had developed between Arabs and Jewish people in Mandatory Palestine.

The end of the British Mandate for Palestine was formally made by way of the Palestine Act 1948 of 29 April. A public statement prepared by the Colonial and Foreign Office confirmed termination of British responsibility for the administration of Palestine from midnight on 14 May 1948.